Hope Springs Eternal

When was the last time you picked up a long and thorough study by a professional historian that you couldn’t put down? Ruth Harris’s new book, published to critical acclaim by the academic and literary communities, may well do the trick for you. It provides an elegantly written, intelligible entry into the world of social anthropologists and historians for a general readership, without sacrificing scholarly criteria or rigor. Lourdes explores the story of Catholicism’s best-known modern Marian shrine as a reflection of larger socio-religious issues swirling about in France during the latter half of the 19th century.

Harris, a fellow and tutor in modern history at Oxford University, brings the social historian’s discipline to bear on a phenomenon of popular faith and piety. While she describes herself as a secular Jew, at first turned off by her subject, Harris came to be both impressed and moved by what she saw and experienced during visits to the shrine. Her academic enterprise took on the guise of a personal pilgrimage. She assisted volunteers caring for the sick and took the ritual bath in order to participate in the raw physicality of Lourdes that impresses its visitors and infuses its spiritual power. The result of her integrative approach is an innovative, interpretive study, with dozens of fascinating photographs, well worth examination. It moves beyond careful documentary research to the mysterious recesses of "body and spirit" that Harris sees as essential to the paradoxical history of Lourdes itself.

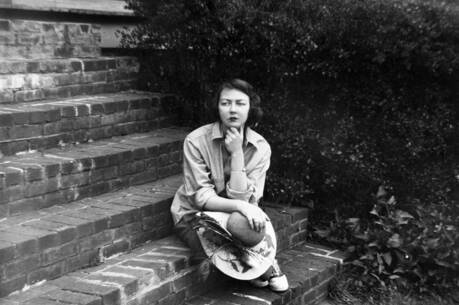

The name of Lourdes evokes a spectrum of memories in the Catholic mind: Marian apparitions, pilgrimages, miraculous cures; vials of "Lourdes water" being transported worldwide; a distressing commercialization of religion; ecclesiastical debates and divisions; the triumph of traditional faith over the secularizing forces of positivism, industry and science. At both center and periphery is the frail, enigmatic figure of Bernadette, upon whom are projected "many different longings of different eras." Some of us recall being herded as elementary school children to a local movie theater for Hollywood’s romantic projection of Franz Werfel’s "Song of Bernadette." Such attempts to romanticize, politicize or medicalize the story of Lourdes, Harris concludes, serve only to fix the imagination on "the essential image of a young, poverty-stricken and sickly girl kneeling in ecstasy in a muddy grotto." That image is where Harris wisely begins and ends her quest to retrieve a historical context that appeals to believer and nonbeliever alike.

The book is straightforward in plan and language. Its political framework covers the critical period of French Catholic history from the Second Empire to the Third Republic. Two major sections, divided into 10 chapters and an epilogue, develop the story of the shrine within that larger history through the lenses of geography, its main characters and the way it grew, like a devotional Topsy, into the most popular pilgrimage site in the Christian West.

Part One introduces the reader to the "Lourdes of the Apparitions," placing the events of 1858 within the context of Pyrenean economic crisis and religious culture. After recounting the familiar story of the apparitions to Bernadette, Harris describes reactions and interpretations "from below," among her family, friends, pastor and the swelling crowds of local folk who came to the grotto of Massabieille to witness the later apparitions. There is a revealing treatment of the changing iconography of the "the white lady," and its subsequent transformation by those who became the apparition’s official interpreters. Documentary evidence taken from interviews with Bernadette describes the figure she first named Aquéro [that thing] as a very young girl of about 12, "no bigger than herself." Harris situates this depiction squarely in popular folklore and in the Western mystical tradition. She refers to Teresa of Avila’s vision of Mary as a very young child. She further shows how the initial rejection by the clergy and elite of Bernadette’s portrayal turned to acceptance upon the apparition’s declaration identifying her with the newly proclaimed doctrine of the Immaculate Conception. All was well. Bernadette’s vision lost its girlish aspects and was replaced by the more acceptable "Immaculate Mother" of official Catholicism.

Similarly, Bernadette herselfthe first saint to be photographedwas reconstructed in official images and journalistic treatments. Harris points out, however, that these constraints on her official image never dimmed the brightness of her authenticity. The historical Bernadette revealed "a quiet charisma, a sure gaze, a conviction of the truth of her story, a dignified rejection of gifts, and a simple generosity that stunned those who knew her poverty." Thus she becomes a sainted paradigm of the piety of the poor and the longings of the sick, a forerunner of liberation spirituality. Moreover, she embodies one of Harris’s main themes: the agency of the poor and of the socially marginalized, especially girls and women, in shaping a modern Catholicism of remarkable resilience and vitality.

Subsequent chapters introduce other main characters who appear on the stage of the Lourdes apparitions. There are the copycat visionaries and healers who appear within weeks of Bernadette’s experience. There are the influential figures of the local bishop, a nanny employed by Empress Eugénie and several journalists, including the ultramontane Louis Veuillot.

In Part Two, the "Lourdes of Pilgrimage," Harris traces the emergence of leading personages and rituals in the making of a modern national shrine. She presents the literary figures, hierarchy, Assumptionist priests and a horde of women devotees, along with the compelling witness of bodily cures, to substantiate her thesis that religion and science were not divided but in a symbiotic relationship at Lourdes. There is a contemporary ring to her treatment of the "Battle of the Books," a war of words over who was writing the authentic truth about the apparitions and their aftermath. The role of right-wing, militant, monarchist and anti-Semitic leadership among the Assumptionists and other radical ultramontanes is treated fairly, but it remains marginal to Harris’s primary thesis, which shows Lourdes as "overcoming the mind-body divide of contemporary society."

Lourdes exemplifies refreshingly engaged and engaging historical writing. It deserves a wide readership.

This article also appeared in print, under the headline “Hope Springs Eternal,” in the May 20, 2000, issue.