'Hijacked'

The Conservative Soul is a dense, passionate argument for a simple thesis: In the United States, true conservatism has been hijacked by the forces of fundamentalism, rendering the Republican Party increasingly unacceptable to principled conservatives. In Andrew Sullivan’s narrative, fundamentalism represents not an extreme of conservatism, but rather its denial. Fundamentalists claim to know the single truth with certainty; conservatives believe that knowledge is at best provisional. The fundamentalist mind-set abhors doubt; the conservative celebrates it as the human use of reason. The fundamentalist sees morality and faith as propositional, organized around dogmatic truths and rigid laws; the conservative sees them as forms of learned practice, as habits of the heart.

The conservative favors limited government; the fundamentalist insists on a robustly interventionist government acting with paternalistic intent. The conservative favors limiting government through constitutions that mediate among differing beliefs and faiths through common means and procedures rather than shared ends or purposes. The conservative distinguishes between public and private; the fundamentalist insists on the application of public principles to private life, using coercion as needed. The conservative insists on the separation of church and state; the fundamentalist rejects this as a form of dogmatic secularism. Fundamentalists believe in foreign policy as great crusades guided by grand notions of history and utopian fantasies; conservatives see foreign policy as a sober matter of self-defense and the abatement of violence in a mostly anarchic international system. The conservative distinguishes between earth and heaven; the fundamentalist yearns for, and wants to accelerate, the coming of heaven on earth. Above all, the true conservative reveres individual freedom, conscience and choice, while the fundamentalist sees them as adversaries of what is known, with certainty, to be Good and True.

Sullivan, senior editor at The New Republic, has certainly captured a defining element of contemporary American politics. The Republican Party of 2006 is dominated by religious conservatives far more than was the party Gerald Ford and Ronald Reagan vied to control 30 years ago, and the influence of these conservatives has been deeply felt in foreign as well as domestic policy.

Oddly (for a well-trained political philosopher and serious Catholic), Sullivan runs into more difficulties at the level of theory and theology. Let me begin where he does, with conservatism. Sullivan declares, sensibly enough, that the need to conserve is the essence of any conservatism. But he fails to draw the obvious inference, that conservatism will therefore be a local matter. Because Britain and the United States have different traditions, the substance of what British and American conservatives seek to conserve will differ accordingly. Because the idea of rights as both unalienable and self-evident, which Sullivan spurns as pertaining to liberalism rather than conservatism, is woven into American tradition, it would be surprising if American conservatives did not rise to its defense, as many do.

In a similar vein, Sullivan insists that all conservatism begins with loss; the hope (often against hope) of resisting loss by slowing if not stopping change is what motivates the desire to conserve. Again, a plausible if not original proposition. But Sullivan does not take the next and necessary step. He does not ask whether the skepticism he embraces and the freedom he endorses are consistent with the impulse to conserve, or undermine it. Socrates, whom Sullivan invokes along with Montaigne as the archetype of the reasonable skeptic, was hardly a force for conservatism. Whether or not they should have executed Socrates, the Athenians were not wrong to see him as politically corrosive. The conservative, says Sullivan, sees his grasp on truth as always provisional, because the human mind is inherently fallible, limited, capable of deluding itself and seeing what it wants to see. I cannot imagine a better description of the scientific mind-set, yet modern science is anything but a conservative force. The freedom of thought and action that Sullivan places at the center of his political philosophy is a human good of a very high order, but its thrust is hardly conservative.

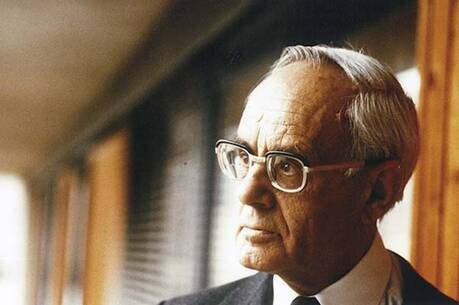

The late philosopher Michael Oakeshott was a critic of rationalism in human life. In both morals and politics, he taught, the heart of the matter is sound practice, not true doctrine; and sound practice is the sort of thing one learns not by reading, but by doing. This teaching, which Sullivan endorses and expands to cover faith as well, generates all manner of difficulties. It leads him to mischaracterize the U.S. Constitution as dealing only with means and procedures, overlooking the Preamble, which declares in no uncertain terms what the Constitution’s purposes are and by clear implication what they are not (the blessings of liberty but not the promotion of virtue, the common defense and general welfare but not the inculcation of the One True Faith, and so forth).

Most astonishingly, Sullivan’s Oakeshottian stance leads him to deny the force of principles or dogmas and to insist that our religion is simply what we do. I am not a Catholic, but Sullivan insists he is. I had always thought, perhaps mistakenly, that Catholic practice could not be disentangled from Catholic doctrine, that devices such as the catechism were designed to instruct Catholics in that doctrine, and that the Catholic hierarchy had as one of its principal purposes the elucidation of right doctrine. While Catholicism is hardly blind to the centrality of love in Jesus’ teachings and example, it cannot accept the sharp antithesis Sullivan creates between love and doctrine, or between love and law. Love unconstrained by truth and not translated into rules of conduct risks error or worse.

This article also appeared in print, under the headline “'Hijacked',” in the November 6, 2006, issue.