Sometimes a museum is more than a place to preserve and present great works of art. Sometimes it carries its visitors into another world. The exhibit, Illuminating Faith: The Eucharist in Medieval Life and Art, on display through Sept. 15 at the Morgan Library & Museum in New York, provides a beautiful display of illuminated manuscripts from the late middle ages (mainly the 12th to the 14th centuries) but also a glimpse into the attitudes and practices surrounding the celebration of the Eucharist at the time. Acquired by Mr. Morgan between 1902 and 1912, these manuscripts reveal the connection in popular piety between the sacramental presence of Christ’s body and blood in the Mass and the physical body and blood of Jesus sacrificed on the cross. These texts and artwork make no reference to the risen Christ and his glorified body, but only to his passion and death.

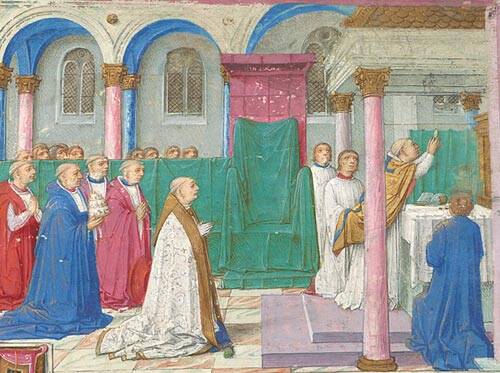

While the term eucharist comes from the Greek word for “thanksgiving,” that attitude is not the emphasis in the art of this period. Both the descriptions of the liturgical practices of the time and the illustrations express the sense of awe that the faithful felt in the real presence of Christ’s body and blood. The laity were commanded to receive Commu-nion once a year, and that became the regular practice at the time. The highlight of the liturgy, according to the testimony of these manuscripts, was not the moment of the consecration of the bread and wine but rather the action immediately afterward, the elevation of the host so that the congregation could gaze upon it in a “spiritual communion” or an “ocular communion” with Christ. Beginning in the early 13th century, priests were encouraged to raise the consecrated host as high as possible so that it could be viewed by everyone.

Simply as artistic creations, the books are splendid. The collection of approximately 65 manuscripts—missals, books of hours, private prayer books and choir books—range in size from a 3-inch by 5-inch domestic prayer book from Belgium to a 3-foot by 2-foot choir book from Milan. The texts are written in the traditional monastic Gothic script surrounded by elaborate floral decorations on the margins, often featuring gilt highlights. The depictions of the Last Supper and of Christ’s Passion and death are rendered in delicate and realistic detail in the relatively tiny spaces of most of the books. The most frequently recurring image is that of the crucified Christ, often with his blood pouring out of his wounds into chalices held by angels, a direct connection with the presence of Christ in the consecrated wine.

A variety of the illustrations, however, veer away from the strictly biblical scenes. One striking image that reoccurs is a depiction of Jesus in a winepress, being crushed to death by the beams of the cross. Another crucifixion scene displays the blood of Christ pouring down to cleanse the skull of Adam at the base of the cross. Another picture shows Jesus sitting on the ground at Calvary, patiently waiting to be nailed to his cross. In a book of hours from the 15th century, an image of a woman representing the church, Ecclesia in Triumph, is situated above another female figure, Synagoga, blindfolded and defeated, representing the people of the Old Testament and possibly the Jewish people of the time. In the lower border of a psalter, for some reason, a mermaid is depicted combing her hair! And the marginalia of two of the manuscripts from the 14th century illustrate parodies of the eucharistic ceremonies involving some seriously scatological images involving animals that need not be described here.

Liturgical Oddities

Some of the illustrations also offer some surprising peeks into the liturgical practices of the time. One of them shows a cleric assisting Pope Leo X in his preparation for Mass, helping him into his “liturgical stockings” and his “pontifical sandals.” One of the other liturgical objects is the “pax board,” a flat piece of painted glass, silver gilt and enamel with a handle. The accompanying commentary claims that from the earliest days of Christianity the kiss of peace involved actual kissing between the priest and the congregation. But sometime in the 12th or 13th century, this practice was replaced by the use of the board with a small circular decoration near the bottom of page. The priest would kiss it first, and then members of the congregation would come up to the altar rail to kiss the pax.

A few liturgical vessels are included, the most impressive of which is the 14th-century Chalice of St. Michael, constructed of silver gilt and multi-colored enamel, created for the Abbey of St. Michael in Siena. Oddly enough, in a time when devotion to the Blessed Sacrament outside of Mass was encouraged and widely practiced, there are no monstrances customarily used to display the host for public devotion. The employment of monstrances came into common practice relatively late, sometime in the 15th century.

This exhibit includes some more exotic and darker elements. There were many stories of eucharistic wafers that shed blood; the most famous of them was the Bleeding Host of Dijon. Given to the Duke of Burgundy by the pope in 1433, it was already treasured for its occasional flow of blood, considered a miraculous event. One book of hours displays a picture of the bleeding host. Copies of the picture were sold as souvenirs to the faithful who came to see the host on display in a monstrance. The very fact that the host survived intact in the monstrance for more than 300 years was considered miraculous in itself. The host was finally burned publicly in 1794 by French revolutionaries. Unfortunately, other instances of bleeding hosts were considered to be caused by acts of desecration by Jews and often provided another excuse to persecute them.

Finally, the exhibit offers an account of the institution of the Feast of Corpus Christi by Pope Urban IV in 1264, celebrating the body and blood of Christ present in the sacrament of the Eucharist. In most countries, the feast is celebrated on the Thursday after Trinity Sunday; in the United States, most dioceses observe it on the following Sunday. It became a very popular holiday, featuring a major procession and often accompanied by mystery plays, which were inspired by biblical stories, and other bits of revelry, religious or otherwise. One of the books on view depicts an elaborate procession led by the pope himself in the piazza of the pre-Renaissance Basilica of St. Peter. The procession through the streets of Rome was revived a few years ago by Pope John Paul II and is now held every year.

This year it received more than the usual attention. Instead of riding on a platform truck, kneeling in front of the Blessed Sacrament, which was the practice of his recent predecessors, Pope Francis walked behind the truck from the Basilica of St. John Lateran to the Basilica of St. Mary Major.

By happy circumstance I chose to visit the exhibition at the Morgan Library on a Thursday recently. Accustomed as I am to the celebration of Corpus Christi on a Sunday, I was surprised to hear the announcement from one of the docents that the day of my visit to the library was the very feast of Corpus Christi observed by the universal church this year. Not quite a miracle, but a lovely connection to the church of the Middle Ages as well as to the eternal presence of the Son of God in the Eucharist and in his people.

View select images from "Illuminating Faith."