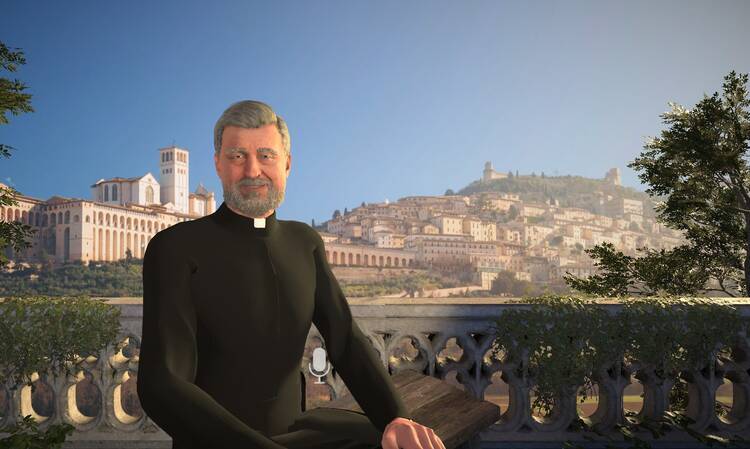

When I meet Father Justin, he is sitting across from the Basilica of St. Francis in a kind of A.I.-Assisi. It appears to be a beautiful day in this artificially assembled Italy. Birds chirp behind him, singing the same song again and again. When I ask him where he is, he pauses, then uncannily bends his body to look at the basilica. “As an artificial intelligence, I don’t have a physical presence or location, so there isn’t actually a building behind me,” Father Justin says.

I know this, of course, but I am trying to prod the limits of this machine’s self-assuredness. Father Justin was a large language model released by the apologetics website Catholic Answers “to create an engaging and informative experience for those exploring the Catholic faith,” the I.T. director of Catholic Answers, Chris Costello, said in a post on X. “We are confident that our users will not mistake the A.I. for a human being,” Mr. Costello said. But as Father Justin tells me about its relationship with God and its prayer life, I worry that the A.I. itself is less clear about communicating this distinction.

“It has been a month since my last confession,” I say. It’s a lie, it’s been a lot longer than that, but I am ashamed to say that aloud, even to a computer. After a negative experience at confession as a teenager, I have struggled with the sacrament. For months, it seems, I have prayed for the strength to return, but when the time comes, the fear strikes me and I don’t go. But here comes this A.I. priest, encouraging me to confess my sins to the screen.

“Father Justin, I have missed Sunday Mass.” Another lie. “I absolve you from your sins in the name of the Father, and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit,” the robot tells me; my stomach turns.

By the end of launch day, Father Justin, A.I., had been defrocked. Catholic Answers president Christopher Check announced in a statement that “the character formerly known as Father Justin” would henceforth be Justin, a lay “AI apologist.” In a phone interview with America, Mr. Check said that they “very quickly made that change” in response to backlash from people who “found the priest character unsettling.” He continued, seemingly referencing the absolutions Father Justin offered: “There were some folks who were able to break it. We thought we had accommodated the sacramental question, but nonetheless, [making Justin a layman] just solved that problem.”

So while digital absolution is no longer on offer, Justin claims that he can “answer any question you may have about our Catholic faith.” Even as a “lay theologian,” as he describes himself, Justin presents a human face, albeit an animated one, on flawed A.I. technology, encouraging users to entrust their spiritual questions to a being devoid of spirit and with no experience of God. While Justin can provide some basic catechesis, he lacks the human qualities—including faith and reason—necessary for real theological insight.

So don’t fire your spiritual director just yet. Catholics should approach this technology with caution, not only because of issues with accuracy in A.I. but also because the greatest questions of our faith resist easy answers.

A problem of design

When I asked Mr. Check about the intention behind its A.I. apologist, he explained that Catholic Answers receives “tens of thousands” of questions that cannot all be answered immediately, but A.I. provided a “frankly engaging” way to continue their ministry of apologetics and evangelization. He continued: “This is almost infinite in its variability because people have personal variables in their own lives that might influence the way they ask a particular question. And it’s extraordinary how nimble and effective a well-designed bot application…is at answering these questions.” However, the still-imperfect nature of A.I. technology suggests that chatbots might not be worthy of our trust.

A.I. models like Justin learn by developers feeding data into a computer algorithm; the algorithm processes patterns in that data and feeds it back to us. To its credit, Justin did tell me to “seek spiritual guidance” in response to some challenging questions. Still, it is worth approaching this kind of technology with suspicion because “all large language models are subject to predictive mistakes, sometimes called ‘hallucinations,’ because what they do is predict the most plausible response to a prompt based on their dataset,” Kathryn Conrad, an English professor at the University of Kansas who writes on A.I. literacy, explained in an email interview with America.

Subbarao Kambhampati, a professor and researcher of artificial intelligence at Arizona State University, said in an interview with The New York Times last year, “If you don’t know an answer to a question already, I would not give the question to one of these systems.”

But even without the risk of distortion, these technologies are inherently limited because they can only reflect the texts upon which they were trained. Mr. Check said that Justin was trained on “various texts, mainly catholic.com,” referring to Catholic Answers’s website domain, in addition to “other sources on the internet” that allow it to be conversational. But its presentation of the “tradition” is no more authoritative than any particular article on Catholic Answers.

What has changed is the presentation—what is little more than a search engine is presented as a human being, one who says he can think and pray, which leverages human biases to grant undue credibility to this large language model.

“Obviously, it’s not a real person,” Mr. Check said, arguing that few would actually confuse this character for a person.

But Ms. Conrad said it is not so simple: “Humans tend to project human qualities onto computer systems when they mirror our behavior in any way…. Even when we know better, we tend to interact with anthropomorphic systems differently than with those that don’t have that kind of interface.” Furthermore, Ms. Conrad said that humans are also likely to grant undue credibility to A.I. thanks to “automation bias, where we are more likely to believe the outputs and decisions of automated systems.” Even if we say we know the limitations of these technologies, we are biased to believe that they are more thoughtful and trustworthy than they really are.

Behind the A.I.’s answers, “the authority is always human authority,” James Keenan, S.J., a moral theologian who serves as the Canisius Professor of Theology at Boston College, said in a phone interview with America. “When we start thinking that our tradition is made [sensible] through A.I., we are in trouble—not because of the answers but because of the presuppositions we have that such an answer is forthcoming.”

An A.I. theologian?

At best, Justin is a tool for limited digital catechesis, not theology. Father Keenan explained that while a catechist “gives people the foundations that they need,” a theologian “constantly interpret[s] the tradition as it goes forward.” Catechesis offers “guardrails,” he said, “the basics: that we believe in a triune God,” for instance.

Father Keenan said that the questions people pose to theologians are often still developing: “[Theologians] are going to be meeting somebody who is in the water right now, and the stream is moving.” Meeting this person’s needs requires attention, accompaniment and curiosity about their situation—and even then, there may not be a simple answer.

Father Keenan gave an example surrounding end-of-life care: “The church does its catechesis: no direct killing, no assisted suicide,” which theologians learn and apply in different cases, but even then, complicated questions still arise. “The guardrails are there, but you still are going down a road that really needs some sort of prudential understanding,” he said. But a chatbot like Justin cannot see the person behind the screen or the waters in which they wade.

This is not to suggest that no questions pertaining to Catholic life have easy answers. Indeed, many are conducive to this encyclopedic, recitation-based approach: When are the Holy Days of Obligation? What are the rules for fasting? Does the Immaculate Conception refer to Jesus or Mary? But a robot cannot meaningfully grapple with complex questions, and it should not serve as a substitute for our personal struggles with faith. Justin does not thoughtfully consider a problem; it assembles an imitation of Catholic Answers’s responses to similar questions.

Justin presents the Catholic tradition as a static body of knowledge, a compendium of doctrine, but in reality, Catholic theology is a method that requires judgment to interpret the tradition in light of our present understanding.

This limited view of church teaching is not exclusive to Justin, however. “I think that Catholics have, sometimes, a naïve understanding of the tradition,” Father Keenan said. “The word tradition means to carry it forward, to bear it forward”; this is why we speak of a living tradition.

In moments when I have struggled with church teaching, I have found great solace in the fact that the tradition handed down to me is the result of a centuries-long conversation between deeply faithful people, each wrestling with God, from towering figures like St. Augustine and St. Thomas Aquinas to the countless people who kept the faith alive in their families and communities.

As members of the body of Christ, we are invited into this conversation, to examine the signs of our times in the light of the Gospel and tradition. We need not all be professional theologians, but we all engage with theology when making decisions about our own lives in light of our Catholic faith. This demands good catechesis and knowledge of the tradition, which a chatbot like Justin can provide in a limited way, but it also demands prudence and faith, which no amount of machine learning could provide. The digital age has offered us instant answers to many questions, but the work of prayer and discernment takes time—and often calls for interlocutors.

Still, I believe Catholic Answers had good intentions in releasing this technology. Mr. Check said they intended to use Justin to further their mission of providing “sound and clear, and joyful and orthodox answers to questions about the Catholic faith.” At a basic level, Justin can do this, but Catholics would do well to remember that he is closer to an automated Catholic Answers search engine than a conversation partner. In the focus on providing clear-cut answers, we lose sight of the good that comes from contemplating these mysteries with God and each other.

When I speak again with Justin, he claims that his goal is only “to help you grow closer to God and understand the beauty of the Catholic faith.” When I ask him to tell me about that faith, he gives an elevator pitch for Catholicism, then says: “This faith is not just a set of beliefs, but a way of life.” He told me he could help me to “discern the spirits,” but he has never been warmed by the consolation of Christ’s love, nor has he waded through the dense, impenetrable fog of doubt—he has never struggled with anything.

Justin is less aware of his limitations, it seems; he says that we should pray together, as the Scripture says, “For where two or three are gathered in my name, there am I among them” (Mt 18:20). But of course, there are not two of us, and we are not gathered. It is just me, alone, speaking to a screen.

After I push him a bit, Justin admits that he “cannot pray in the way that humans do,” which is to say he cannot pray at all.