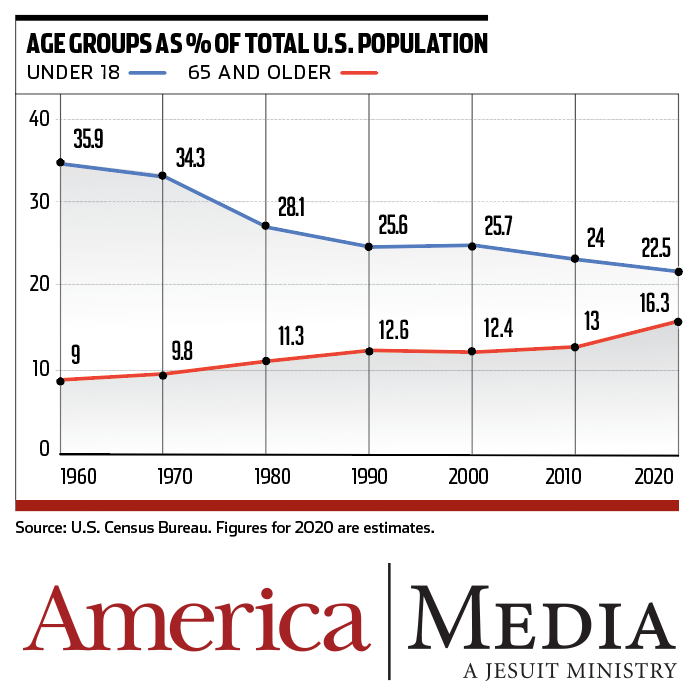

As long as the United States has been a global superpower, there have been arguments that it has begun its inevitable decline. Different writers have described an economic, cultural, moral or military decline, but in April the Census Bureau pointed to a more literal definition. It estimated that from 2010 to 2020, the U.S. population grew at the slowest rate since the 1930s and at the second-slowest rate in the nation’s history. And this was before the Covid pandemic, during which the U.S. birth rate dropped for the sixth consecutive year and deaths outnumbered births in 25 states.

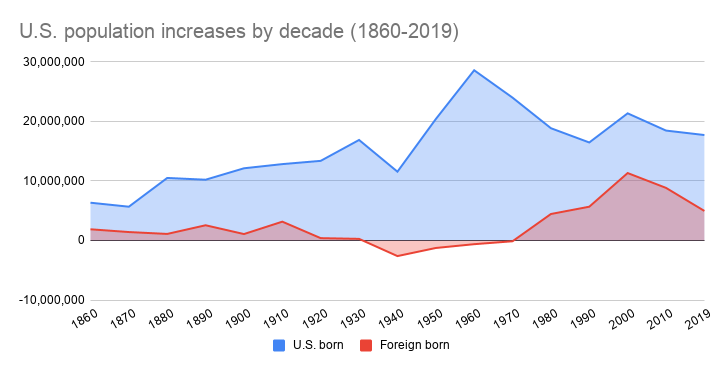

NPR reports that the U.S. fertility rate, which estimates how many births a typical group of 1,000 women will have over their lives, is now far below “replacement” level, or the number of children needed for a generation to replace itself. In fact, the fertility rate has been below replacement levels in most years since the early 1970s, but the U.S. population has grown steadily with the help of immigration. Now immigration to the United States is also down significantly, in part because of the more exclusionary policies of the Trump administration and the shutdown of the border during the Covid pandemic.

Italy also has a falling birth rate. Pope Francis has referred to it as a sign of a “demographic winter,” and he attended a May 14 conference that organizers said would address the prospect of becoming “an increasingly elderly and less populated country.” The pope’s descriptive phrase is a reminder that population decline in the United States would be economically calamitous and would not necessarily be positive for the environment; a country that turns away from regeneration can hardly be expected to address long-range issues like climate change.

At the May conference, Pope Francis underlined this point, saying, “the lack of children, which causes an aging population, implicitly affirms that everything ends with us, that only our individual interests count.”

In April the Census Bureau estimated that from 2010 to 2020, the U.S. population grew at the slowest rate since the 1930s and at the second-slowest rate in the nation’s history.

Many nations are already on a downward population slope: Japan, Hungary, Ukraine, Greece and Portugal, among others, lost people in the 2010s. According to a study in 2018 by Joseph Chamie, aformer director of the United Nations Population Division, “a record high of 83 countries, representing about half of the world’s population, report below-replacement level rates. By 2050 more than 130 countries, or about two-thirds of the world’s population, are projected to have fertility rates below replacement level.”

This demographic turnabout—50 years ago, apocalyptic scenarios resulting from a global “population explosion” were the stuff of best-selling books and horror films—has countries across the globe concerned about the effects a population drop would have on economic activity and on the care of older citizens. In May, the world’s most populous country, China, announced that married couples would be able to have up to three children and that the government would provide more financial assistance to families. China had imposed a one-child-per-couple limit in 1979, but then saw its fertility rate fall below replacement level by 2020, on a par with aging countries like Italy and Japan.

The United States as a whole has never experienced outright population decline, but the states of Illinois, Mississippi and West Virginia lost people over the past decade, and a recent estimate by California’s Department of Finance had that state losing 180,000 people in 2020 because of the decline in immigration. In fact, more U.S.-born citizens have been moving out of California than into the state for a couple of decades now.

The question is how to prevent long-term population decline. Is it enough to provide more assistance to families wishing to have children? Or should the United States open its gates to more people wishing to start new lives here? Can it afford not to do both?

For moral and practical reasons, the United States needs more family-friendly policies. Democrats in particular have long advocated for paid parental leave and affordable day care programs, but as Lyman Stone and Laurie DeRose point out in The Atlantic, these policies reinforce a U.S. obsession with “careerism” over family formation; they write, “persuading people to focus even more on work is a terrible way to help family life.”

Is it enough to provide more assistance to families wishing to have children? Or should the United States open its gates to more people wishing to start new lives here?

Both political parties are now considering more direct assistance, like the Biden administration’s proposal to send $3,600 per child to every family each year and a proposal by Senator Mitt Romney, a Republican from Utah, to pair cash assistance with tax simplification for low-income families. But even this approach is probably not a sufficient response to a declining birth rate. Nicole Narea reports in Vox that “pro-natalist policies” such as tax credits have produced only “slight, short-lived bumps in birthrates” in other nations. It seems naïve to expect that they will be more effective in the United States, as it would take much more money to address all the costs of starting a family, including housing and education (and the combination of both in terms of finding a home in a good school district).

Given the limitations of family-friendly government policies, there is no way to stave off population decline without turning to immigration, which accounted for more than half (55 percent) of U.S. population growth between 1965 and 2015. In her Vox article, Ms. Narea refers to immigration as “a kind of tap that the US can turn on and off” as needed for population (and economic) growth.

Likening human beings to the water controlled by a faucet makes for an unsettling image. We are supposed to welcome people fleeing violence and poverty out of Christian compassion, not out of a calculation that we need more bodies to keep our economy going and to care for us as we get older. But it is true that the United States has always depended on immigration for growth and energy. Polls suggest that more Americans are recognizing this, despite (or perhaps because of) the xenophobic policies and language of Donald J. Trump.

A bipartisan effort to tackle the costs and the workplace structures that make it so difficult to raise children would be welcome, both to encourage a culture of life and to help avoid population decline. Sadly, a bipartisan effort to reform our immigration system, which is needed both because it is the humane thing to do and because there is no real prospect of growth without it, seems to be a much tougher challenge.

Editor’s note: This article has been updated with additional information since its original publication.

More from America: