Editor’s Note: This interview appeared in the print edition of America on May 8, 1993. Four years previous, Mr. Sullivan—who is openly gay and a practicing Catholic—had published the first major article in the United States to advocate for the legalization of gay marriage (“Here Comes The Groom,” The New Republic, 8/28/1989), an argument he extended in two later books, Virtually Normal (1995) and Same-Sex Marriage: Pro and Con (1997). Mr. Sullivan was the editor of The New Republic from 1991 to 1996, and is the author or editor of six books. A prominent public intellectual for over 30 years, he now publishes political commentary at The Weekly Dish.

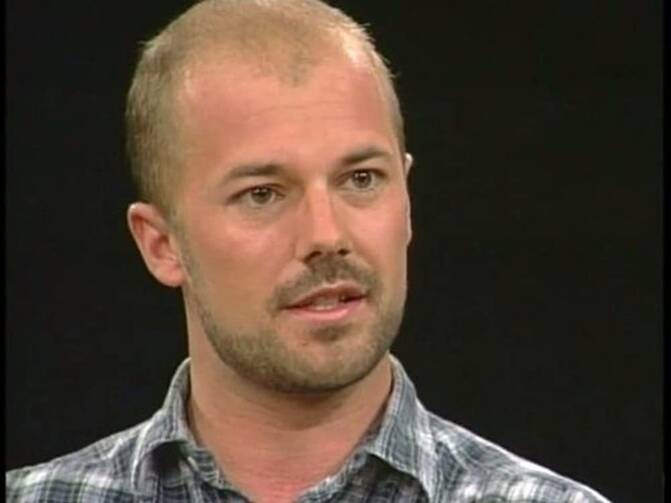

Andrew Sullivan, 30 years old, is editor of The New Republic. English by birth, Mr. Sullivan studied modern history at Oxford University, where he was also president of the Union. He then won a Harkness Fellowship to Harvard and wrote a Ph.D. dissertation on Michael Oakeshott, the British political philosopher. In a talk he gave at the New York Public Library earlier this year on journalism and minorities, he expressed enthusiasm for the openness of American society—citing his editorship of The New Republic as an example of it. His writings have touched on themes, among others, having to do with Catholic thought and gay life. This interview took place in his office at the magazine, in Washington, D.C., March 19, 1993. The interviewer was Thomas H. Stahel. S.J., executive editor of America.

You are both Catholic and gay and open about both, and it would be helpful to others in the church to know how you bring those two parts of your life together, in view of official church teaching on homosexuality and also in view of your evident respect for the Catholic tradition.

Well, part of what I’ve found frustrating is the notion that I’ve made some public announcement that I was these two things—which is not true. The fact of the matter was that both those things were part of my life, as a human being, when I got this job. As a writer, I had written about both areas of my life. As a journalist, my first material—and I’ve always found this—is trying to understand oneself and one’s life through telling these things. That’s why I studied philosophy and theology and why I found myself drawn to writing about and wrestling with issues of sexuality. So it was what everybody else said, it was they that presented this matter as such.

It’s very hard to know where to start in saying how you actually reconcile the two elements, and it is something profoundly personal and private. There were two things I didn’t want to do, however. One, I did not want to lie about either. I did not feel that that was intellectually or spiritually worthy. And I did not want to make an issue of this with the church either. It was foisted upon me. I was asked the questions. As the editor of a public magazine, I was, to some extent, obliged to answer them.

Andrew Sullivan: “I don’t believe that any Christian or any person trying to live a life of faith expects a life which is not full of conflict.”

It was not as if you wished to issue a challenge, then?

No, not at all. And I have not, in anything that I’ve written. I think I’ve been extremely respectful of the authority of the church—I mean, authority as it is understood in the church’s complex notion. That’s not what I wanted to do. I’ve never challenged the church. I’ve always attempted to understand its teachings on sexuality within the context of the teachings of the church on broader notions of sexuality and in general.

On the other hand, of course, I do try and live a life that is not in complete internal conflict. But I don’t believe that any Christian or any person trying to live a life of faith expects a life which is not full of conflict. One of the things I’ve tried to resist is the temptation to resolve contradictions. There are some convictions which cannot be resolved or explained away that have to be lived with. It would be, I think, an insult both to the intellectual coherence of a great deal of the church’s teaching and to what I hope may be the moral integrity of my own and many other people’s lives, to say that contradiction can easily be avoided.

There was a moment once in a talk I gave at the University of Virginia, on the politics of sexuality. At the end of the talk, a young kid, who must have been about 19, said, “I’m struggling with this. I’m gay, and I’m in the church, and I don’t know what to do. Can you help me?” And I said, “No. I can’t help you. I don’t have the moral authority to help anybody.” Undoubtedly, the very fact of my existence, at some level, in the public area, has provoked and prompted an enormous number of letters and an enormous amount of interest from people in exactly the same position—who want desperately to have a life that can be spiritually and morally whole. The church as presently constituted refuses to grapple with this desire.

I’m not being very coherent. If I were writing an article, I’d be more coherent.

Your argument, in any case, has to do with a contradiction that nevertheless cannot be avoided.

There is a basic contradiction. I completely concede that, at one level. At another level—and I confronted this, actually, with my first boyfriend, who was also Roman Catholic. When we had a fight one day, he said: “Do you really believe that what we are doing is wrong? Because if you do, I can’t go on with this. And yet you don’t want to challenge the church’s teaching on this, or leave the church.” And of course I was forced to say I don’t believe, at some level, I really do not believe that the love of one person for another and the commitment of one person to another, in the emotional construct which homosexuality dictates to us—I know in my heart of hearts that cannot be wrong. I know that there are many things within homosexual life that can be wrong—just as in heterosexual life they can be wrong. There are many things in my sexual and emotional life that I do not believe are spiritually pure, in any way. It is fraught with moral danger, but at its deepest level it struck me as completely inconceivable—from my own moral experience, from a real honest attempt to understand that experience—that it was wrong.

I experienced coming out in exactly the way you would think. I didn’t really express any homosexual emotions or commitments or relationships until I was in my early 20’s, partly because of the strict religious upbringing I had, and my commitment to my faith. It was not something I blew off casually. I struggled enormously with it. But as soon as I actually explored the possibility of human contact within my emotional and sexual makeup—in other words, as soon as I allowed myself to love someone—all the constructs the church had taught me about the inherent disorder seemed just so self-evidently wrong that I could no longer find it that problematic. Because my own moral sense was overwhelming, because I felt, through the experience of loving someone or being allowed to love someone, an enormous sense of the presence of God—for the first time in my life.

Within the love?

Yes.

And within the sexual expression of that love?

The mixture of the two. the inextricable mixture of the two. I mean. I felt like I was made whole.

Having made this discovery that you were whole for the first time, how then did you retain your respect and reverence for the church understood as a contrary tradition?

It’s very curious, I think, because I’ve never felt anger toward the church. I know I’m weird in this regard.

Many gay people do feel anger.

Enormous anger, enormous. They’ve left. The depth of the pain that’s been caused people—I mean, real pain—not only by the laity, but by the clergy too, is extraordinary. Honestly and truly, there are few subjects on which the church is now, by virtue of its teaching, inflicting more pain on human beings than this subject—real psychic, spiritual pain. I’m not sure why I don’t feel anger. I have always, I think, assumed that I probably don’t understand enough to experience anger, that the church was never meant to be a perfect institution, that it was grappling and finding and struggling to find its way toward the truth of its own doctrine, the truth of its own mission.

Andrew Sullivan: “I am drawn, in the natural way I think human beings are drawn, to love and care for another person. I agree with the church’s teachings about natural law in that regard.”

The official church teaching is at a loss to deal with homosexuality, in my view, because according to this official moral teaching, homosexuality has no finality. Any comment?

It is bizarre that something can occur naturally and have no natural end. I think it’s a unique doctrine, isn’t it? The church now concedes—although it attempts to avoid conceding it in the last couple of letters—but it has essentially conceded, and does concede in the new Universal Catechism….

Have you seen it?

I’ve read it in French, yes.

What does it concede?

That homosexuality is, so far as one can tell, an involuntary condition.

An “orientation”?

Yes, and that it is involuntary. The church has conceded this: Some people seem to be constitutively homosexual. And the church has also conceded compassion. Yet the expression of this condition, which is involuntary and therefore sinless—because if it is involuntary, obviously no sin attaches—is always and everywhere sinful! Well, I could rack my brains for an analogy in any other Catholic doctrine that would come up with such a notion. Philosophically, it is incoherent, fundamentally incoherent. People are born with all sorts of things. We are born with original sin, but that is in itself sinful—an involuntary condition, but it is sin.

The analogy might be thought to be disability, but at the core of what disabled human beings can be—which means their spiritual and emotional life—the church not only affirms the equal dignity of disabled people in that regard but encourages us to see [that dignity] and to take away the prejudice of not believing a disabled person can lead a full and integrated human life even though they cannot walk or they experience some other disability.

But the disability that we are asked to believe that [homosexuals] are about [sic] is fundamental to our integrity as emotional beings, as I understand it. Now, I have tried to understand what this doctrine is about because my life is at stake in it. I believe God thinks there is a final end for me and others that is related to our essence as images of God and as people who are called to love ourselves and others. I am drawn, in the natural way I think human beings are drawn, to love and care for another person. I agree with the church’s teachings about natural law in that regard. I think we are called to commitment and to fidelity, and I see that all around me in the gay world. I see, as one was taught that one would see something in natural law, self-evident activity leading toward this final end, which is commitment and love: the need and desire and hunger for that. That is the sensus fidelium, and there is no attempt within the church right now even to bring that sense into the teaching or into the discussion of the teaching.

You see it even in the documents. The documents will say, on the one hand compassion, on the other hand objective disorder. A document that can come up with this phrase, “not unjust discrimination,” is contorted because the church is going in two different directions at once with this doctrine. On the one hand, it is recognizing the humanity of the individual being; on the other, it is not letting that human being be fully human.

Andrew Sullivan: “There are many sides to the Catholic temperament and sensibility, but one great strand is its ability to understand the human experience and empathize with it.”

Would you agree that the acknowledgment of this issue within Catholic family life will inevitably change the way the church expresses itself toward people who are professedly homosexual?

I would, probably. My family is an interesting example. My mother is a very devout Catholic. My sister is a devout and practicing Catholic. Both are now pillars of moral and emotional support for me, and for gay people in general. That, I think, is the authentically Catholic response. And the family is the key to broader change. I think that’s how it will get resolved in society in general, because homosexuality—when you actually look at it in people whom you need and love—is a very different issue from when it’s some abstract mode of being or some closeted, repressed mode of being, which is equally abstract. Once it is actually human—well, there are many sides to the Catholic temperament and sensibility, but one great strand is its ability to understand the human experience and empathize with it. That will overcome so much, I think.

Of course, there’s “‘Hate the sin, but love the sinner.” But as we’ve said, it’s no longer that. It’s “Accept the condition, and reject the conditioned.” That’s what it is.

As the church’s present policy...

That’s the present policy. But that will not hold, because it is intellectually incoherent. I have searched in vain for a truly coherent intellectual defense of the position that doesn’t merely come down to “We’re sorry.”

Also, I think that the competence and the change in gay society as a whole, in American society as a whole, will trickle in. I think in a small way, someone like me has an effect on people: Well, here’s someone who looks like a real human being, who is responsible, who can do a job, who doesn’t seem to be depraved or dysfunctional or disordered in any more than a usual sense. Do we really think this person merits this particular censure, so much that we could not tolerate being in the same march or organization or pew?

If you had been a consultor to New York’s Cardinal John J. O’Connor, how would you have advised him to act with respect to gays seeking to march in the St. Patrick’s Day parade? [ED: This conversation took place two days after St. Patrick’s Day.]

He’s in an impossible position. He really is. I think there could have been a far clearer statement from the Cardinal that gay human beings are human beings and that the church fights for the dignity of every human being and fights for the dignity of every homosexual human being. He could have made that statement and distinguished it—however incoherently, but he could have distinguished it—from an endorsement of a particular political platform that approves something the church still believes is a sin.

Once, I remember, I was downtown late on a Sunday afternoon, and I wanted to go to Mass, and I was wearing a gay T-shirt. The question was whether I could go to Mass wearing this T-shirt. And I did, because as a gay person, I am a human being, and the church says that. The way that the Cardinal Archbishop of New York behaved, I think, failed to make that important distinction—which, given the existence of bigotry, was an extremely unnerving stance.

Andrew Sullivan: “What the church is asking gay people to do is not to be holy, but actually to be warped.”

Why would you have characterized his position as “impossible”?

Because the church’s position is so incoherent. You can’t really say, “We love gay people, but you can’t be gay.” You have to assume, if they’re marching as gay people, that they practice. But of course the church is there defining gay people by a sexual act in a way it never defines heterosexual people, and in this, the church is in weird agreement with extremist gay activists who also want to define homosexuality in terms of its purely sexual content. Whereas being gay is not about sex as such. Fundamentally, it’s about one’s core emotional identity. It’s about whom one loves, ultimately, and how that can make one whole as a human being.

The moral consequences, in my own life, of the refusal to allow myself to love another human being were disastrous. They made me permanently frustrated and angry and bitter. It spilled over into other areas of my life. Once that emotional blockage is removed, one’s whole moral equilibrium can improve, just as a single person’s moral equilibrium in a whole range of areas can improve with marriage, in many ways, because there is a kind of stability and security and rock upon which to build one’s moral and emotional life. To deny this to gay people is not merely incoherent and wrong, from the Christian point of view. It is incredibly destructive of the moral quality of their lives in general. Does that make sense? These things are part of a continuous moral whole. You can’t ask someone to suppress what makes them whole as a human being and then to lead blameless lives. We are human beings, and we need love in our lives in order to love others—in order to be good Christians! What the church is asking gay people to do is not to be holy, but actually to be warped.

Technically, the church is asking gay people to live celibately.

Right. But let’s take that for a minute. Celibacy for the priesthood, which is an interesting argument and one with which I have a certain sympathy, is in order to unleash those deep emotional forces for love of God. Is the church asking this of gay people? I mean, if the church were saying to gay people, “You are special to us, and your celibacy is in order for you to have this role and that role and this final end,” or if the church had a doctrine of an alternative final end for gay people, then it might make more sense. It would be saying God made gay people for this, not for marriage or for children or for procreation or for emotional pairing, but He made gay people in order to—let’s say—build beautiful cathedrals or be witnesses to the world in some other way. But the church has no positive doctrine on this at all. You see, that would be a coherent position at some level—that, for some mysterious reason, God made certain people with full sexual and emotional capability and required them to sublimate that capability into other areas of life.

So you don’t really accept the analogy of homosexuality to a handicap?

Not really. There are various ways in which that analogy doesn’t work. It’s not a physical handicap, clearly. It’s not as if there’s a physical impediment. It’s the possible analogy to a mental handicap that is more interesting—because that’s the closest it comes to what one might call an “objective disorder.” But in a mentally handicapped person, the acts that person commits under the influence of that handicap are not morally culpable. When an epileptic knocks someone out in the process of a fit, that act is not regarded as an intrinsic moral evil, as is understood of a homosexual act. The acts of a retarded person are morally blameless insofar as they are produced by their handicap. But with gay people, the condition is like a handicap, but its expression is an intrinsic moral evil!

In the strongest terms one can use, the argument is intellectually contemptible. It really is. It’s an insult to thinking people.

If that’s the worst possible construction that can be put on the church’s present teaching, what is the best?

Well, the best is that human sexuality is procreative, inextricably procreative, and that human beings are somehow meant to be that way, and that any expression of their sexuality is related to Human Life |the title of Paul VI’s 1968 encyclical]. It’s part of a continuous doctrinal argument. Undoubtedly, the impulse behind that reasoning is not merely biological but is to protect and promote human well-being as much as possible.

Do you see homosexual love as procreative?

It can’t be procreative.

Not in the technical sense, but in some metaphorical or otherwise more significant sense than the merely biological?

In terms of the other thing the church understands conjugal love to be about, insofar as it teaches one the disciplines of love, yes, it’s procreative. Marriage in its broadest sense teaches us something, I think, about the love of God for man…. that’s part of it. The permanent commitment of one person to another teaches human beings—the church teaches—what love is. In that sense, the love of one man for another man, or the love of one woman for another woman, in that conjugal bond, teaches exactly the same thing.

There is also enormous capacity, I think, for gay peopie to adopt children. Again, the church does not see that, in its attempt to care about the unborn—it’s never been so imaginative as to say, if we are interested in adoption and caring for children—-which is the important other side of a pro-life stand—here are all these people able to love. Why not put the potential with the need?

Andrew Sullivan: “No wonder people’s lives— many gay lives—are unhappy or distraught or in dysfunction, because there is no guidance at all.”

What has been your own experience of pastoral care within the Catholic Church? Granted the possibility of a difference between official teaching and sympathetic advice of a counselor or priest, have you been well treated?

Yes, in general. But I have to say that I find it increasingly difficult. Once I had lost, at one point, my prime confessor who knew me, it was hard for me to reconstruct it all for someone else for fear of rejection. You never know what you are going to get back. For a Catholic that sometimes is the great … I mean, I’ve heard stories about people who have been wounded, deeply, by brusque treatment, a complete inability to understand what this is about. But, personally, I have nothing but positive things to say.

My parish in Washington is the cathedral parish. I go there for Mass on Sunday, and the congregation must be about 25 percent gay—I mean, it’s the mid-city. There is almost no ministry to gay people, almost no mention of the subject. It is shrouded in complete and utter silence, which is the only practical way they can find to deal with it. Partly, of course—and here I’m not speaking of this particular cathedral or any particular congregation—because of the great tragedy of the church in what it requires of its own gay clergy. I mean, this horrific bargain they have to strike, which is not only are they required to be silent about their own sexuality but, the repression is so great, they cannot even bring themselves to speak about it. It would bring up so much emotion and difficulty that it’s best not even to touch upon it.

This is not a defense of a non-celibate clergy. The gay priest, in a way, would be ideal. If the church were really true to its convictions, it would be perfectly happy with openly gay priests who were also openly celibate, because presumably celibacy is the only issue the church has with homosexuals. Maybe the church should say the final end of all gay people is the priesthood—explicitly rather than implicitly. That would be a final end.

But it doesn’t. It’s crippled by its own internal inconsistency.

I think that in every statement the church makes, given the forces within our society as a whole, it has to be extremely careful that its doctrines not be misunderstood—especially in this matter—for fear that it become an accomplice to all sorts of forces that, of all things, it really should not be an accomplice to. People are beaten up. People are killed, actually, for their sexual orientation—on the streets, in bars, in the military. Slurs are made. This is surely something the church should oppose.

It’s amazing that these distinctions are not made. If the church believed in its own position, it would constantly be making these distinctions, saying, for example, “We can’t accept an explicitly pro-sexual-activity cohort in the [St. Patrick’s Day] march…. But we do believe that gay men and women are human beings, that they have dignity, that they are to be protected, that bigotry against them is to be resisted, that violence against them is to be opposed at all levels.” There are ways in which you can frame these questions. The church has an obligation to teach both—if it’s going to teach this doctrine.

But, you see, I think the church, at the highest levels, does not believe this. I think that on this doctrine, more than many others actually, the church is suffering from a crisis of its own internal conviction. Because homosexuality is not a new subject for the Roman Catholic Church. It is not a distant subject. It is at the very heart of the hierarchy, so every attempt to deal with it is terrifying. But the fact of the matter is, if the church is to operate in the modern world, the conspiracy of silence is ending. So something has to be said. And the something that has to be said has to be coherent, or it will be exposed, as incoherence is always exposed.

There is so much in the church’s doctrine that could give us an ability—even within the current doctrine—to present it in a positive way. I think the inability to do so suggests that, on the part of the hierarchy, there’s a problem.

What are the good and positive elements in the Catholic tradition that could lead us to a more coherent position?

Natural law! Here is something [homosexuality] that seems to occur spontaneously in nature, in all societies and civilizations. Why not a teaching about the nature of homosexuality and what its good is. How can we be good? Teach us. How does one inform the moral lives of homosexuals? The church has an obligation to all its faithful to teach us how to live and how to be good—which is not merely dismissal, silence, embarrassment or a “unique” doctrine on one’s inherent disorder. Explain it. How does God make this? Why does it occur? What should we do? How can the doctrine of Christian love be applied to homosexual people as well?

Now it may be this search will turn up all sorts of options and possibilities. There may be all sorts of notions and debate about the nature of this phenomenon and what its final end might be. But that it has a final end is important. The church has to understand—people in the church have to understand—what it must be to grow up loving God and wanting to live one’s life well and truly, as a human being, able to love and contribute and believe, and yet having nothing.

I grew up with nothing. No one taught me anything except that this couldn’t be mentioned. And as a result of the total lack of teaching, gay Catholics and gay people in general are in crisis. No wonder people’s lives— many gay lives—are unhappy or distraught or in dysfunction, because there is no guidance at all. Here is a population within the church, and outside the church, desperately seeking spiritual health and values. And the church refuses to come to our aid, refuses to listen to this call.

“The church has to understand...what it must be to grow up loving God and wanting to live one’s life well and truly, as a human being, able to love and contribute and believe, and yet having nothing.”

You know, I see something like the AIDS quilt. What an extraordinary and spiritual thing that was, and this was done by people who are denied any spiritual support. What has happened with AIDS is the most extraordinary event for so many people of my generation, who have seen many of our friends die. The spiritual dimension of this event is enormous, and the need for the church to provide some structure, some hope, some spiritual guidance and balm—and nothing! Virtually nothing.

The quilt was in Washington. It is made by families, many of them Catholic, mothers and fathers and sons and daughters, who found somehow in their own lives a way to sacramentalize the lives of their sons and daughters, and to go to the Mall and do it. That afternoon, I went to church. The Gospel was about the 10 lepers who were cleansed and the one who came back to give thanks [Lk. 17:11-19]. This Gospel, on this day of all days—when I had read the names of my friends on a loudspeaker—with its notion of the double alienation of being a leper and a Samarian, like suffering a plague and being gay: It was too perfect.

The sermon was about modern leprosy and how it was being cured. The bidding prayers had no reference to AIDS whatsoever, whereas a quarter of the congregation had been stricken or had seen it directly in their own lives. What is the church for? Could it not see this?

For the first time, I went up to the priest afterward, and I said, “I just want you to know that I’ve just been to the quilt. It’s here in Washington. It’s the most extraordinary event. I came here to pray. I came for what the church is here for, to help me, and to help me understand this. And you said—with this Gospel—you said nothing! Don’t you understand how that must feel?”

He said, “Well, we prayed for the sick.”

“Sure,” I said. “But isn’t there anybody here who can witness to what is happening?”

“Well, you are a witness to it.”

And I said, “Well, you should be the witness to it.”

In other words, there are basic, human, spiritual needs among gays that the church refuses to minister to, uniquely among all human beings. Even to ask the question “How can we help you?” or “How can we inform your moral and emotional life?” That is the church’s first duty to its members and to the world at large, and it’s refusing to live up to it to such an extent that people have to do it themselves. The quilt was a great cathedral, really, a spontaneous cathedral, but it was an indictment of the church’s inability to deal with it.

Andrew Sullivan: “I do not believe the church is an evil institution. I do not believe it wants to hate gay people. I think the church just cannot cope.”

Do you think the church’s denial is hard-heartedness, or fear and confusion?

The latter. I’m not angry at the church, because I do not believe the church is an evil institution. I do not believe it wants to hate gay people. I think the church just cannot cope. It’s like a family that cannot talk about this even though its own son or daughter is gay.

That’s why I think the family is important here...

Yes. If the analogy is complete, nothing can be healed until this can be dealt with.

Maybe the healing will come precisely from the families who deal with the issue more directly at the level of human love.

Exactly.

One problem in that case is that the hierarchy, who are the authorities, do not have to deal with gay children the way your mother did.

Also it’s incumbent upon gay Catholics, just as it is always incumbent upon the gay child, to say, “I’m here.” There’s a two-way street.

You know, I see so many ways in which people are trying to say that, but they are so fearful of the rejection that they can’t say it. I listen to gay America, and I hear this great cry for spiritual help. It doesn’t sound like that a lot of the time. It sounds like anger, or protest. Many of the movements are semi-religious. And look at their tenacity. Look at Dignity, look at what people are doing to insist upon the spiritual possibilities, despite the disincentives.