On Monday, October 16, 1978, all the eyes of the world—at least, the Catholic world, anyway—were centered upon the city of Rome where over a hundred cardinals had gathered in a conclave at the Vatican to elect a new pope to lead the Roman Catholic Church. The cardinals had convened just two days earlier, on Oct. 14, some six weeks after the unexpectedly sudden and shocking death of Pope John Paul I, the former patriarch of Venice, who had been elected on Aug. 26 to succeed Pope Paul VI (who had died on Aug. 6, on the Feast of the Transfiguration). When it would be all over, 1978 would become known as “The Year of the Three Popes,” only no one knew that at the time, back then, when the August conclave commenced and resulted in the election of a humble and smiling pastor, who loved God, his fellow human beings, as well as the written word, both sacred and secular.

The death of John Paul I was as swift as his election: he was hardly among us, and then he was gone. As the dean of the College of Cardinals, Cardinal Carlo Confalonieri, said at the time of the pope’s funeral, he was like a meteor in the heavens that flashed in the skies and then disappeared. Such was the impact Albino Luciani had in his brief pontificate of 33 days. The suddenness of his death gave rise to rumors of foul play among some, but such talk were simply gossip and intrigues that certain people of such mindsets engaged in, in an attempt to explain the unexplainable, when it was simply an unfortunately sudden death of a 65-year-old man. It would be remarked later that the suddenness of his election and the enormity of the responsibilities that were placed upon him had hastened his untimely demise of a man who was, health-wise, far from robust. It was no small thing to have been just the bishop of a small—though important—diocese and find oneself in the next moment the religious figurehead of nearly a billion people in the world.

He had simply no time to write any encyclicals or make any major pronouncements on policy or procedure or appoint officials to specific positions; by the end of those days he was just beginning to become accustomed to being what he was: the pope. He would be known and remembered for his pastoral sensitivity and ability to connect with the general public; he was a gifted catechist who could summarize complex theological ideas so that even the most seemingly unlearned person could understand and appreciate. He lived simply, was always cheerful, and went about his duties with a quiet confidence in God. It was not for nothing that his episcopal motto was summed up with just one word: humility. Not long after, the story went around that during one of his Wednesday audiences, a little girl at the back of the crowd in St. Peter’s Square, excitedly tugged at her father’s sleeve, saying “Daddy, Daddy! I can understand what the pope says!” Such was the gift of “The Smiling Pope.”

So, when the cardinals assembled again, the following October, they, no less than their fellow co-religionists around the world, were left to wonder what the future held for themselves as well as the universal church. As for myself, on that October afternoon in 1978, I had just turned 17 years old that summer and was in the early months of my junior year at St. Nicholas of Tolentine High School in the Bronx. I was as intrigued as any of the august cardinals as to whom they would select to be the next pope, while my fellow students had more urgent concerns: how Bucky Dent and the New York Yankees would fare that year’s pennant race.

Papal elections were as exciting as presidential elections, perhaps even more so, given the color, the pageantry and the history that surrounded those historic assemblies. I forget now what class I was in that afternoon; but truth to tell, my mind was wandering about who would become the next pope instead of the lesson that was in front of me and of the nun that was likely at the head of the class. That very day was just “one of those days” you wished something dramatic would happen, in the hope that the doldrums of the late afternoon would be shaken off and pushed aside, not to mention the lesson (or lessons) we juniors were enduring that day, hoping for it to be over with.

Little did I know when the ancient intercom box atop the the blackboard suddenly came to life, with the telltale noise of the microphones being jostled around (with the loudspeaker magnifying every sound of that jostling) for the big announcement, whatever it was. So when the intercom buzzed, so did we.

Our principal, Fr. Michael Hughes, O.S.A., made the announcement that Catholics everywhere—and the junior ones in that Bronx classroom—were waiting for with bated breath: a new pope was chosen to lead our old—and everlasting—church. We wondered who it could be. We all knew that the election of Albino Luciani was a one-in-a-million thing, that he was a special man we were all fortunate to know in that all too brief month he walked among us, and in our hearts we knew that there could never be another one like him. (In fact, in honor of the late pope, our high school chapel was named the “Pope John Paul I Memorial Chapel,” under the custodial care of our chaplain, the Rev. Alfred E. Smith, O.S.A., the grandson-name-sake (and the eerily look-alike) of the legendary New York governor and 1928 presidential candidate.) What could the Holy Spirit come up now? In a few seconds, we had our answer: Cardinal Karol Wojtyla, archbishop of Krakow, Poland, 58 years old, athlete, poet, and singer of songs. A Polish pope!

In the midst of all the handclapping, shouts and whistles, I frowned: Cardinal Wojtyla? Wasn’t he the very old forbidding man who was always fighting with the Communists? I would learn very quickly that I had the new pope confused with his now former cardinalatial colleague, the Primate of Poland, Stefan Cardinal Wyszynski. The primate was the older of the two, and the better known. (And besides, I hadn’t known that there were two Polish cardinals.) It was shocking to watch on television the scene from half a world away when, on a moonlit night, the new—and vigorously young—pope appeared on the balcony of St. Peter’s before the world and its television cameras as the newly-elected Pope John Paul II.

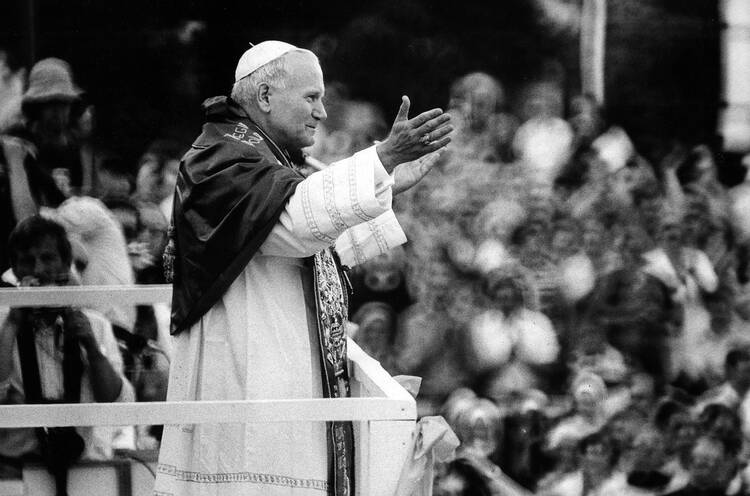

His bearing was vigorous, as was his voice: you noticed that when he spoke, he didn’t have the halting—though friendly—tones of his lamented predecessor who hailed from the Veneto. The new John Paul was broad-shouldered, self-assured man, who, with a twinkle in his eyes, surveyed the scene the scene that lay before him that October night. (When the moment came when he was elected, he actually planned to declare as his papal name, Stanislaus, in honor of his Slavic heritage. He was persuaded to choose instead the same double-barreled name his predecessor chose, in honor of Popes John XXIII and Paul VI as well as to assuage the grief the people were still feeling over the beloved pope’s untimely passing.) The crowd in the square began to hear an Italian that they never heard before: one that was Polish-inflected, and one which they would hear many, many times in the future. With an apology for not speaking correctly what he called “your” (which he quickly changed to our) Italian language, and with his winsome ways and sure touch with the masses, he quickly won over an anxious populace still in mourning over their beloved Papa Gianpaolo. “The Pope From a Far Country,” as he described himself, thus began a momentous 27-year pontificate on that moonlit night.

Little did Karol Wojtyla know on that moonlit night what lay ahead of him: the encyclicals, the meetings with statesmen and governmental leaders, the political and religious controversies (inside and outside the church), the “rock-star” persona that would envelop him with his mass rallies with youth throughout the world and the eventual creation of the “World Youth Day” that was such a singular contribution of his attempts at outreach to those who were the future of the church. And then there was the assassination attempt in 1981, a year in which two other world leaders would be assassin’s targets, along with him: Egypt’s President Anwar Sadat (who would die immediately from his wounds), and President Ronald Reagan. Both President Reagan and Pope John Paul II would severely wounded, and both would survive, though barely. (In the aftermath and after his recovery, the pope would have a well-publicized meeting with his assailant, offering Christian forgiveness to his “Muslim brother.”) The jubilee year, the great number new saints created for remembrance at the altar; the rapprochement with “our elder brothers” in faith, the Jews, and most poignantly of all, the serenity and fortitude with which he bore his final illness which robbed him of the freedom of mobility and the efficacy of speech. All of these things and more lay ahead of him that night; and all of them were part of his path to sainthood which everybody soon realized on the day of his death on that April day in 2005, on the eve of the Feast of Divine Mercy, the creation of which was another one of his spiritual gifts to the church.

It is hard, now, to think of a public figure who lived in our times—and someone we all knew and were familiar with—as a saint, as in the case of Pope John Paul II. We expect our popes to be “saintly,” though we do not always expect that they will eventually become saints. Saints are those we were used to seeing in paintings and as statues on top of pedestals. John Paul II was a person living in the world, just as we were: he was definitely no statue or painting saint. The Karol Wojtyla who was Pope John Paul II started out life as “child of God” through his baptism, but he was someone who was also somehow touched by God in his inscrutable designs to someday affect the course of history, his church and humankind. Though deeply religious, he was warmly human and as a human, he was subject to the imperfections and flaws we all share; yet the pilot light of faith burned brightly within him as it did with his predecessor of the same name, the first John Paul. (The first John Paul is also considered by many to also be a saint and who, in time, will surely be proclaimed one.)

Each John Paul was special in their own way and both will always have a hold on people’s affections and will continue to do so, long after their deaths have receded into history and long after those summer days in 1978 when they were both elected to assume an office neither of them would have ever dreamed of occupying, days which, before long, will no longer be a living memory.

Oct. 22 (which is the anniversary of John Paul II’s installation as pope) is now recorded in the church’s liturgical calendar as being the feast of now Pope Saint John Paul II. It is not to retract from the life of this pope-saint, John Paul II, to say that we would not have had him had it not been for the brief time of Albino Luciani, the first Pope John Paul. Even he had an inkling that he would be succeeded by the man whom he supposedly called “the foreigner,” one who had sat across from him in that August conclave. It is remarkable to think that in those days of 1978, the Holy Spirit descended upon these two different—though very remarkable—men of faith and presented them to the world as popes for a while and as eventual saints not only for our time, but for all time.

It is something worth remembering on this feast day of Karol Wojtyla, and also have gratitude for Albino Luciani, who proceeded him. Each in their own way showed that there is no one way to love God—or to follow him—as long as we do it, and that we can take comfort in the knowledge that it is possible for fallible –though loving and lovable—human beings to accomplish such a great thing as being or becoming a saint.