Patricia Lockwood is the author of two poetry collections, Balloon Pop Outlaw Black and Motherland Fatherland Homelandsexuals, a New York Times Notable Book. Her writing has appeared in The New York Times, The New Yorker, The New Republic, Slate and The London Review of Books. She was born in Fort Wayne, Ind., and now lives in Lawrence, Kan.

Ms. Lockwood’s father, the Rev. Gregory J. Lockwood, is a priest of the Archdiocese of St. Louis, Mo. He was ordained in 1988 as a married convert to Catholicism and was a former Lutheran pastor. Ms. Lockwood writes about her father with humor—“All fathers believe they are God, and I took it for granted that my father especially believed it”—and an indelible sense of grace, despite their different views of the world: “I was not made in his likeness, but I have chosen something of his same extremity, his willingness to be available for the questions that knock on the door in the middle of the night.”

Ms. Lockwood’s latest book is a memoir, Priestdaddy, which was published on May 2. I interviewed Ms. Lockwood by email about this book.

Do you think the Catholic Church has a sense of humor?

The church itself might not, but individual Catholics do. Individual Catholics are some of the funniest people I’ve ever known. Actually, some of the biggest laughs I’ve gotten at my readings have been from little old ladies in the front row with gold crosses around their necks.

How does having a father as a priest affect your perception of the priesthood (as job, as identity)—both during your childhood and now?

I think I wrote in early drafts of the book that I “saw the Catholic Church from the inside, like a tauntaun.” That goes for the priesthood as well. From my vantage point, they were a group of men who wore fewer clothes, drank more alcohol, collected jewels like they were in a video game and were occasionally caught in compromising positions in public parks. But they were also people who had chosen weird lives, had devoted themselves to the service of an idea. And I like that. I like people who choose weird lives.

I saw the Catholic Church from the inside, like a tauntaun.

Like your father, I’m obsessed with “The Exorcist” (although I’m a few shy of his 72+ viewings). What seems so Catholic about that film to him—and to you?

The fear you feel when you’re watching “The Exorcist” is not a fear for your body, exactly, but more a fear for your soul. It’s about the larger battle between good and evil, and whether you can be conscripted to fight for the wrong side against your will. That’s some of the most frightening makeup ever put on screen, but it registered to me only as an afterthought—the real terror was in the idea.

The house, too, seemed reekingly Catholic, like a rectory my family might have been assigned to in some nightmare scenario. Also, they were always eating some really depressing ’70s meal, which is as Catholic as it gets.

On the first page of the memoir, you write a description of your husband in your father’s rectory: “Jason presses his shoulder against mine for reassurance and tries to avoid making eye contact with graphic crucifix on the opposite wall, whose nouns are like a poem’s nouns: blood, bone, skin.” Later, when Jason asks you, “What exactly do Catholics believe?” you start off “First of all, blood. BLOOD.” It’s funny but true. How would you explain Catholicism to people who don’t know the faith? What makes Catholicism, well, Catholic?

It’s really an extreme literalism coexisting side by side with mysticism. We’re the ones who’ve chosen to believe that when Jesus says, “This is my body and this is my blood,” he really means it. Because Jesus doesn’t mess around! So that’s literal, but he himself is a metaphor come to life, a metaphor so condensed and powerful it’s only a single word.

Do you have favorite or influential Catholic writers and artists?

Teresa of Avila, Augustine, Aquinas, Gerard Manley Hopkins. Muriel Spark, Rebecca West. Eliot and Donne almost count!

You wrote, “faith and my father taught me the same lesson: to live in the mystery, even to love it.” What do you think of when you talk about “mystery”?

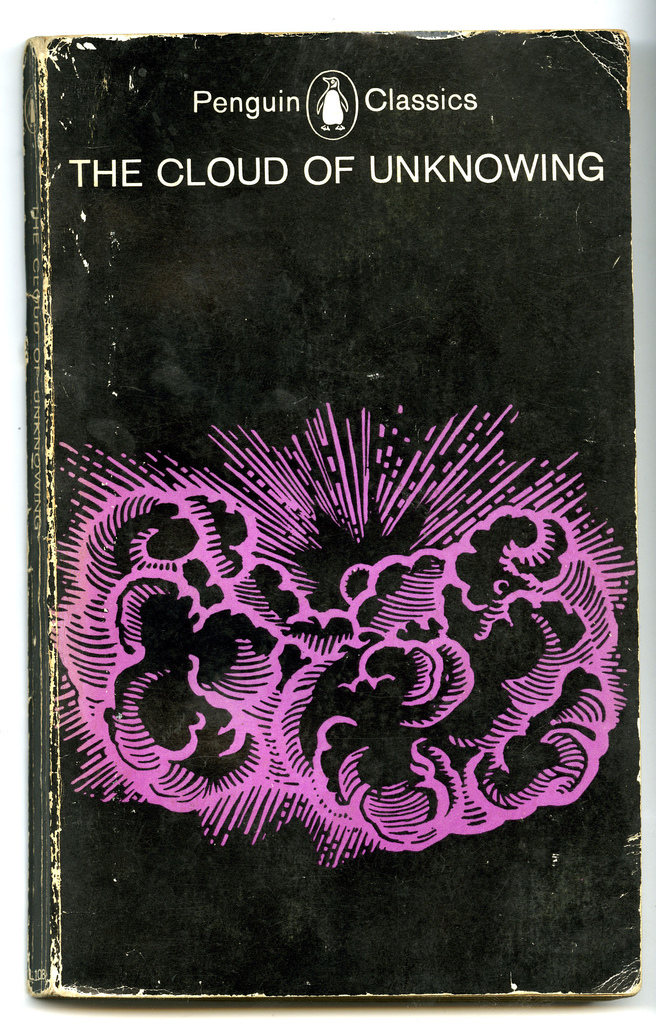

My literary sense of mystery has almost certainly been infected with the Catholic one. When I read the word “mystery,” even, I see that old Penguin Classics cover of The Cloud of Unknowing that’s just a ball of clouds with rays of light shooting out of it, and the mystery is at the center like a brain beyond all brains.

I love how you write about your mother: “Sometimes it strikes me that when my mother is gone, I will remember her most vividly in rest-stop bathrooms, rubbing her hands under the keening dryer, smiling at me adventurously in the warp of the mirror and fluffing her hair with her fingertips.” How did it feel writing about her?

It felt very joyous and affectionate, whereas with my father it was much more fraught—much more like stepping across a landmine. There’s an ebullience about my mother, a generosity not just of spirit but of movement and humor and language that is coming out of her at all times. Later in the book, I write that being with her is like existing at the center of a cornucopia, and that’s really how it feels.

Venerate Mary all you want, but if you can’t show even a fraction of that respect to the women you encounter on a day-to-day basis, how much is it worth?

You became close with a seminarian who was staying in your parents’ home. In one scene before his ordination, you think that your relationship will soon change: “particular friendships with women will be discouraged. I understand why, but in a wider sense, it is frightening. If you are not friends with women, they are theoretical to you.” Looking back, do you miss that connection? How do you view women and the church (including your mother, yourself)?

Because of my father’s unique position, we saw a lot more hierarchical, behind-the-scenes sexism than the average Catholic probably did. There was the bishop who always asked my mother why she wasn’t home with her babies, the priest who always called her by the wrong name because he thought it was funny, the men who ate the meals she cooked them and drank the wine she poured them and never ever thanked her. It was so, so strange, especially in the light of what these men claimed to love. To put it bluntly, venerate Mary all you want, but if you can’t show even a fraction of that respect to the women you encounter on a day-to-day basis, how much is it worth? If you only love Mary because she was pure, because she was untouched, because she was without sin, you do not love her at all.

Priestdaddy is hilarious, but there are also so many solemn moments of graceful paradox—as when you hear church bells and think “Go and tell John what you hear and see” and then say “The words rang with meaning, because I had been raised that way. That is the vestigial organ of religion—the voice that speaks, the hand that reaches out to hold.” Does that voice ever speak to you now?

The hand is still very much there—it’s what tells me to genuflect and cross myself in a church, to sit down and stand up with the rest of the people.

The voice comes to me mostly now as a set of rhythms—the patterns and stresses of the Bible and the liturgy. The words are not necessarily present, but the beats are there intact. I feel them when I write.