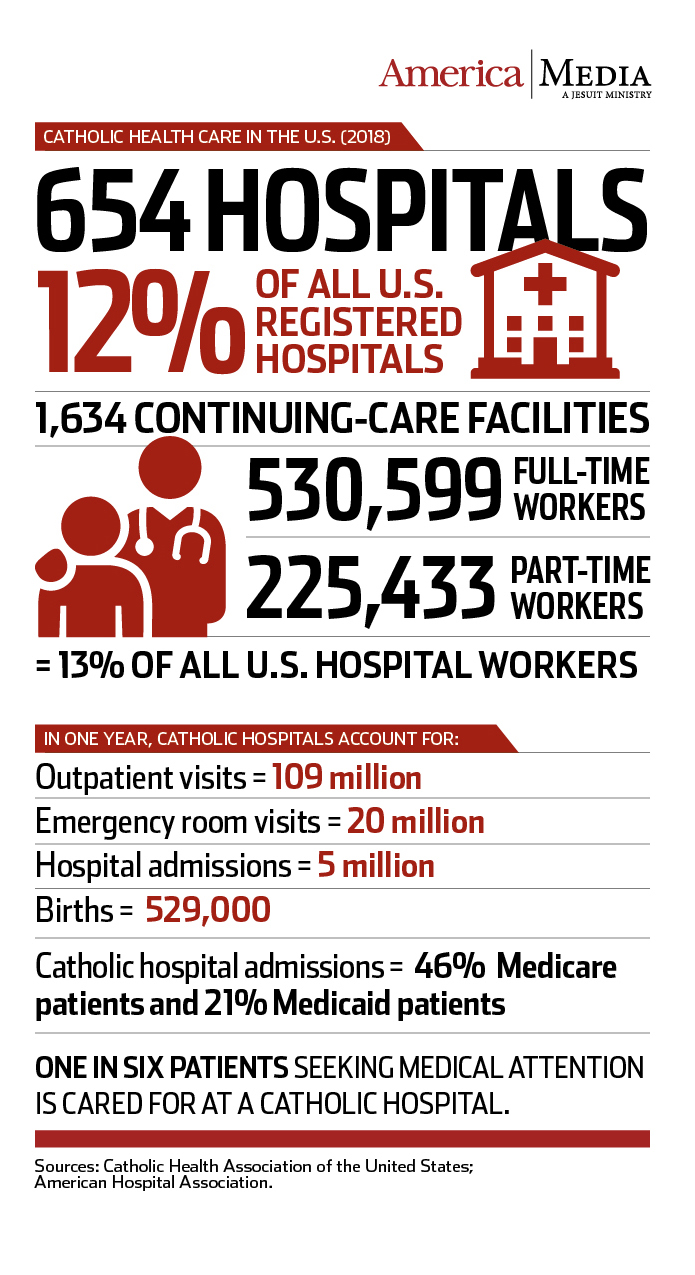

The member institutions of the Catholic Health Association of the United States—654 hospitals and more than 1,600 continuing care facilities—face the same demands as their secular peers: among them containing the galloping costs of new technologies and drug therapies, retaining staff, and maintaining expertise.

But Catholic institutions confront some unique challenges too, said Carol Keehan, of the Daughters of Charity, president and chief executive officer of the Catholic Health Association. Catholic institutions can accept Pope Francis’ call for a church that goes to the margins “like a field hospital” quite literally. “As you look at our footprint across the country,” said Sister Keehan, “Catholic health care remains an integral part of the health care of this nation. We’ve done it since the beginning of this nation and we continue to do it.” In fact, each day in the United States one in six patients seeking medical attention is cared for at a Catholic hospital.

Going to the margins to open or maintain health services does not always earn C.H.A. members accolades; sometimes it provokes unfriendly scrutiny. Catholic institutions have come under fire when they turn out to be one of the few or even the only health care provider still standing in urban and rural communities that have been abandoned because of difficult logistics or economics.

The often vehement criticism focuses on services—contraception, sterilization, elective abortion, gender reassignment therapy or surgery, and acts of euthanasia—that Catholic institutions will not offer. “Being true to the mission of Catholic health, we want to be respectful and welcoming and caring for all patients in the context of still saying there are some things we are not going to do,” said Sister Keehan.

“We want to be respectful and welcoming and caring for all patients in the context of still saying there are some things we are not going to do.”

In times past those limitations on specific services might have seemed reasonable to most people; in recent years, however, Catholic health services have frequently been attacked for purportedly improperly caring for women or transgender patients because of such restrictions, a charge Sister Keehan strongly denied. She pointed out that Catholic hospitals must follow the same accreditation regimen and offer the same standard of care as any other health care provider. They often provide the highest level of care, she said, for women facing problem pregnancies.

The attacks from the A.C.L.U. and a handful of other groups are part of a broader polarization Sister Keehan sees at work in contemporary U.S. society. “The vitriol, the lashing out at people, the diminished respect for each other and the atrocious way [disagreements are] often expressed in public” is something she said many Catholic health care administrators are still adjusting to. Sister Keehan cited recent comments about Senator John McCain of Arizona, who is approaching death but still objecting to torture revivalism in the Trump administration. “There just seems like there is no boundary that people won’t cross anymore.”

The polarized environment—“when you’re dealing with people making accusations [about the mistreatment of women patients] that are outrageous or vicious”—makes it “really very tough,” she said, “sorting out the challenges affecting the Affordable Care Act and sorting out a reasonable respect for the conscience of each person.”

And dealing with scurrilous attacks is a distraction from the more positive work hospital staff could be doing, she argues. Sister Keehan recalled a webinar offered by C.H.A. in December on meeting the spiritual needs of patients who were experiencing different levels of dementia. “We had 400 people on that webinar,” despite the upcoming holidays, she recalled. “That is how sensitive people in Catholic health care are to the importance of total care of the patient.

“Now that was a really good use of our time, but getting into these polarized conversations and responding to deliberate misinformation,” Sister Keehan said, can be draining for health care administrators and staff.

But asked about the greatest challenge confronting the national Catholic health network this year, Sister Keehan’s response was instantaneous. “The absolute disruption of the health care delivery system by efforts to destroy the Affordable Care Act” in Congress and the White House, she said.

Before the 2016 elections, Sister Keehan said, C.H.A. member institutions had been considering how best to support the expansion and stabilization of what has became popularly known as Obamacare. Instead they have been consumed by a rear-guard effort to preserve the A.C.A.’s achievements.

She called the passage of the A.C.A. in 2010 the greatest step forward in U.S. health care since the creation of Medicare and Medicaid in 1965. “We saw 20 million people who did not have insurance get insurance,” she said. Instead of building on that progress and addressing some of the major deficits of the A.C.A., she said, the Trump administration has exhausted itself on unsuccessful efforts to legislatively euthanize Obamacare before seeking its death “by a thousand cuts” through regulatory reversals and underfunding awareness-raising efforts.

“We are destabilizing not only the health care delivery for low-income people but for middle-income people,” she added. Owing to the uncertainty created by Trump administration policy shifts like repealing the mandate that individuals acquire insurance coverage, she said that insurers have been raising rates on all policyholders, not just those receiving government-subsidized insurance.

Those hikes have been accompanied by rising copays and coverage limitations reminiscent of the kinds of restrictions the A.C.A. was created to address. Those limits can deter even well-insured people from seeking medical care they may need, a return to pre-Obamacare form that will likely contribute to poorer health outcomes in the United States and lower revenue for some already hard-pressed C.H.A. member institutions.

Despite such challenges, Sister Keehan insists it remains a “wonderful time” to be working in Catholic health care, giving no small part of the credit for that to the lift provided by Pope Francis and his many encouragements. He has been “laser focused,” she said, on the important role of health providers in relation to the church’s other priorities, including supporting the family and global migrants, and assisting people out of poverty. “You have such a sense that this holy father understands how important health care is and its importance to the credibility of the Gospel message,” she said.

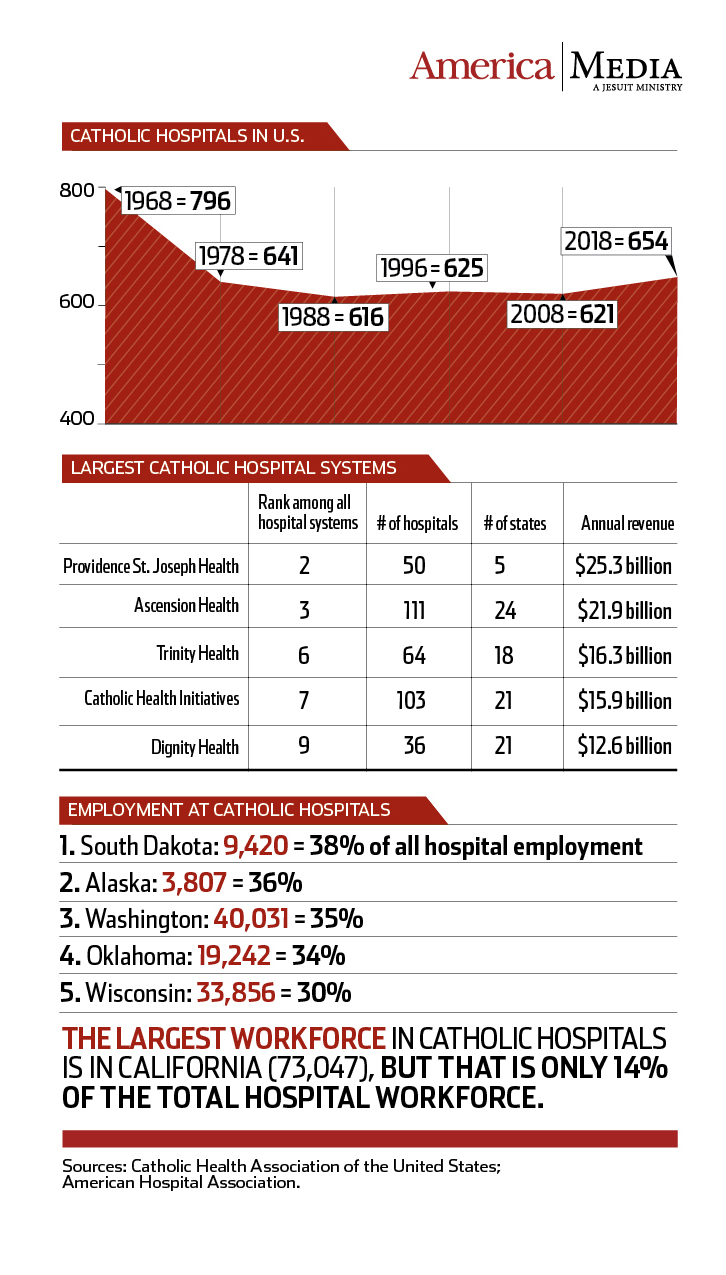

Infographic sources: Catholic Health Association of the United States; American Hospital Association. Number of Catholic hospitals unavailable for 1998; chart instead notes number from 1996. According to the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project, 39 percent of all U.S. hospital admissions in 2012 were Medicare patients and 21 percent were Medicaid patients.

There are too many examples of women not getting treatment at Catholic hospitals that jeopardize the lives of the women. Women who are in the process of miscarrying a child & are in danger of hemorrhaging. As a result, they are sent to other hospitals that will treat them. That's why Catholic hospitals are being sued. For not providing care. And if a doctor or hospital will not care for people who have life threatening medical issues, they should not be in "business". For it to happen once is too many times.