The weekend on which the church’s Synod on the Family began deliberations coincided, by chance, with the opening weekend of Gone Girl, one of the most provocative and disturbing films about marriage, gender and family to be mounted in the United States in recent memory

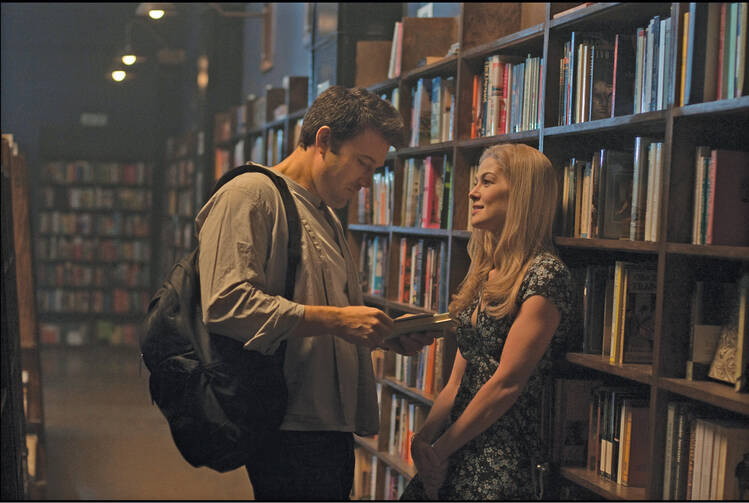

The story, based on Gillian Flynn’s massively successful 2012 novel of the same name, is about Amy Elliott Dunne, a Missouri housewife who disappears mysteriously on the morning of her fifth wedding anniversary, perhaps at the hands of her bar-owner husband, Nick. For those who have read the book and wonder about the quality of the film adaptation, it’s safe and spoiler-free to call it an impressive adaptation: 2 hours and 20 minutes of oh-my-Baby-Jesus-did-that-just-happen sorts of choices and twists enacted by an extraordinary cast (including Ben Affleck as Nick) and demanding conversation afterward.

There is a lot about “Gone Girl” that makes it relevant to the synod (warning: spoilers ahead). On the one hand, many aspects of the film’s hellish vision of marriage are, I suspect, all too familiar to most people who have been in a troublesome, long-term relationship. It is a touchstone for the challenges of being married, the wounds couples can suffer and also inflict, and the real ways in which a relationship can go wrong.

On the other hand, when the mystery of what’s happened to Amy is revealed, “Gone Girl” presents a very disturbing image of women, one that may be more dangerous than it is illuminating.

One of the key issues the synod addresses is the place of divorced Catholics within the church. One of the truths that underlies that conversation is that marriage is hard—very hard. People often say marriage has its up and downs. But these difficulties are rarely discussed in specific terms: the sense of suffocation (and/or the desire to suffocate) that partners sometimes feel; the moments, if not long periods of temptation; the bouts of gnawing restlessness or frustration.

The film is a meditation upon those dark depths, an unrelenting look into the pettiness, cruelty and even madness that sometimes simmers under the surface in any long-term relationship. Although reviewers are calling it a great date movie, I suspect “Gone Girl” will evoke many painful memories. Its characters go to terrible, crazy extremes; yet the core of their battles always remains eerily and firmly familiar, a more extreme evocation of our own experiences of wound and sin. As difficult as that makes the film to watch, such depictions can be freeing as well. The insanity we have known, the terrible choices we have sometimes made—it’s not just us. When it comes to relationships, perhaps especially marriage, we can all get a little crazy sometimes.

People wonder why anyone bothers with the sacrament of reconciliation anymore; yet a story like “Gone Girl” reminds us just how desperately we all need a place where we can come clean and be forgiven. We rightly grieve over marriages that break up, and in its own strange, bleak way, “Gone Girl” illustrates the costs involved in that separation. And it suggests perhaps we should also stand in amazement and gratitude to God that so many couples manage to make it through dark times and survive in honest, healthy ways.

Yet “Gone Girl” is a thriller that ends by confirming every horrible claim and revenge fantasy abusive men might make—that women are manipulative, vindictive, psychotic, unpredictable, dangerous, inescapable, in need of punishment. Amy Elliott Dunne is no innocent victim; she turns out to be a sociopath who frames not only her husband but two other men as perpetrators of sexual abuse.

I have been trying to tell myself that this twist does not matter. “Gone Girl” is a work of fiction, after all, not a term paper on gender roles or values. It was also written by a woman and has been read by many book clubs made up of women. (A group like this was seated around me in the theater.) The story includes some wonderfully rich female characters, including Nick’s sister, Margo (excellently played by Carrie Coon) and the lead detective (played by Kim Dickens, who really should be in just about everything).

Let’s be honest: both men and women are capable of violence, lying and manipulation. But this world that we live in, the world that the next stages of the synod, we hope, will consider in all its rich and painful ambiguity, is a place where misogyny and domestic abuse against women are prevalent. In the United States alone, over 20 percent of women report that they have been the victims of sexual assault in their lifetime, and 25 percent are victims of domestic abuse. Celebrities and athletes have made headlines of late for instances of alleged abuse. And in many countries, women and girls find both their lives and their bodies in regular, grave danger. The last thing we need in a world like this is a character whose story of deceit might cause people to view real-life victims with undue suspicion. Nor do we need a story that invites us to embrace fears and revenge fantasies ourselves.

The author, Gillian Flynn, has said that demanding that her female characters be good or pure is confining. I sympathize with her argument. It is always more fun to write about the sinners than the saints. But to imply that the character of Amy Elliott Dunne represents some sort of a “liberation” is absurd. “Gone Girl” may raise deep questions about marriage, but when it comes to its portrayal of women, I can’t help feeling that it is irresponsible.

And yet the film certainly has people talking, and conversations around issues of abuse and sexual violence are sorely needed. One hopes that as our church continues to discuss the struggles and needs of couples and of women that it can help turn this conversation into real action, ministering to the messiness of our lives.