In an interview the African-American artist Alma Thomas gave in the last year of her life, she described light sifting through a holly tree outside the bay window of her home in Washington, D.C., as the inspiration for her commitment to abstraction. Her color harmonies, she explained, were based on her flower beds—especially as imagined from above. In a late-blooming career, she had moved beyond polemics about the “mainstream” of art for art’s sake and the “blackstream” art concerned with civil rights in the era. “Through color,” said this resolute artist, “I have sought to concentrate on beauty and happiness, rather than on man’s inhumanity to man.” Now a dazzling if relatively modest exhibition at the Studio Museum in Harlem—more than 50 paintings and works on paper—offers a celebration both for those who already love her and those who soon will.

The eldest of four sisters, Thomas was born in 1891 in Columbus, Ga. Her father was a businessman, her mother a dressmaker. In 1907, Jim Crow racism led the family to move to Washington and to the home in which Thomas lived for the rest of her life. During high school she concentrated on math and science but in 1924 became Howard University’s first graduate in fine arts. Ten years later she earned a master’s degree in arts education from Columbia University Teachers College and then between 1950 and 1960 worked on a master’s in fine arts in painting from American University.

Thomas taught at Shaw Junior High School to support herself, and only after retiring in 1960 could she work entirely on her art. During her teaching years, she built patiently on the influences of James V. Herring at Howard and Jacob Kainen at American University. In the late 1940s she frequented the “little Paris salon” that Loïs Mailou Jones organized for black artists. Kainen introduced her to the Washington Color School painters, Kenneth Noland, Morris Louis, Gene Davis and Sam Gilliam. (Thomas’s work came to be associated with this school, as well as with other abstract expressionists, but she herself resisted labels, including “black artist,” and remained determinedly independent.) During her summers at Columbia she discovered the modernist artists shown at Alfred Stieglitz’s An American Place. And in Washington she helped to found the Barnett-Aden Gallery, at the time one of the country’s few private galleries showing the work of African-American artists.

The Studio Museum’s exhibition, the first overview of her work in almost 20 years, is divided into four sections: one briefly on the artist’s move to abstraction, the next on imagery based on abstractions drawn from nature, then a gallery presenting work inspired by her interest in space technology and finally some splendid large pieces from her later years. A generous selection of works on paper, largely from the Columbus Museum of Art in Georgia, and mostly undated, also shows the artist working experimentally and honing her skills.

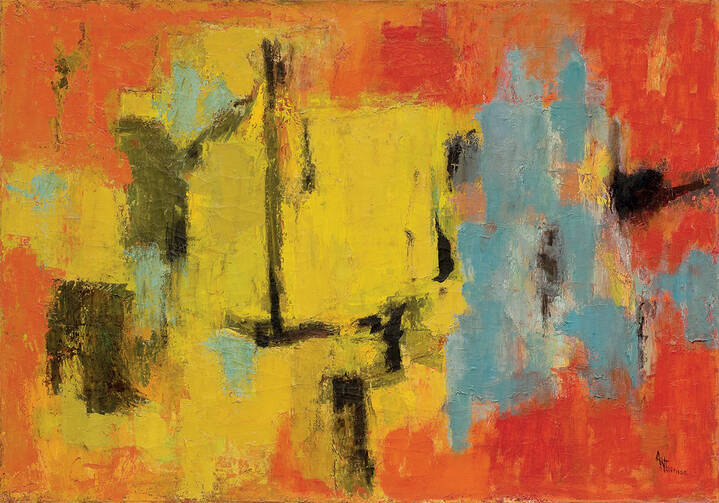

While the show does include two semifigurative sketches for her painting of the 1963 March on Washington (in which she participated), “Yellow and Blue,” from 1959, signals her real direction, with daubs of yellow tinged with chartreuse and turquoise blue structured by black linear elements and floating not on but in an earthy red. With another abstraction hanging nearby it exudes a sense of aspiration, a rising of the spirit, which continues in the “Earth” series from 1968-69. These large, acrylic-on-canvas pieces seem at first to be stippled vertical, and sometimes circular, stripes of shimmering bright colors, harmonized so musically that your eye will dance back and forth over their surface. Closer inspection quickly reveals that the stripes are composed of daubs or patches of color over a white ground and that you might as well be looking down on them from above rather than directly at them in front of you. A further organizational refinement occurs in the largest and best of these paintings, “Wind, Sunshine, and Flowers” (1968), in which slight separation between the patches of color creates delicate white arcs that loop rhythmically, as if in the wind, across the painting. Our aspiration begins with and returns to experience of the earth.

Thomas had begun “to think about what I would see if I were in an airplane,” and became enthusiastic about NASA’s space program, news of which she followed eagerly on her radio. The resultant cosmic scenes, in structure and color, resemble her other work of the period but convey still, after almost 50 years, the thrill of early space exploration. “Snoopy Sees Earth Wrapped in Sunset” (1970) is a glowing red, yellow and orange globe set on a smudgy rose background. It might seem whimsical except that “Snoopy” is what the astronauts called their wheeled vehicle on the moon. A new optical effect appears here, as the white spaces between the daubs of red can appear to be just that or like glyphs on a red ground. The same optical effect appears in the imposing “Starry Night and the Astronauts” (1972), which takes us out into the great darkness of space with a flash of sunset seen from a great distance.

The year 1972 was Thomas’s “banner year,” as she said, with a solo exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art, the first ever given to an African-American woman (she was 80), and later that year another show at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington. At the Whitney she remarked: “One of the things we couldn’t do was go into museums, let alone think of hanging our pictures there. My, times have changed. Just look at me now.”

And look at her indeed. Despite severe arthritis and deteriorating eyesight, she continued in her 80s to paint large, jubilant paintings that moved on from the “Alma stripes” to a more purely abstract, mosaic-like, loosely structured work in a simplified, sometimes almost monochromatic palette. The wonderfully free “Hydrangeas Spring Song” of 1976 carries you into the midst of the bursting blue forms of the hydrangeas. In “Cherry Blossom Symphony” (1973), one of a trio of paintings on that evanescent theme, pink daubs of paint are painted over faint underlayers of blues, greens and reds, and you are either walking under the trees or floating above them. Best of all is the surging “Scarlet Sage Dancing a Whirling Dervish” (1976), with its brilliant scarlet patches subtly organized in 11 whirling, round clusters, its energy gently echoed by “White Roses Sing and Sing,” also 1976, with white daubs (and a few yellow) on a green ground.

When Thomas died in 1978, her reputation was established. But like many other women associated with Abstract Expressionism, she suffered in comparison with “the men.” Yet her art was as timeless as she claimed all creative art is, and it is a balm for us all that she is now receiving new recognition. She is in fact a life-saver. “A world without color would seem dead,” she said in a 1972 interview. “Color, for me, is life.” See her at the Studio Museum through Oct. 30, or at one of the major museums that include her work—and come newly alive.

You have written about this topic so well that even my friends liked it. I got everyone to share it further on. I also got feedback. Pullover Rogue One Hoodie on celebsclothing.com