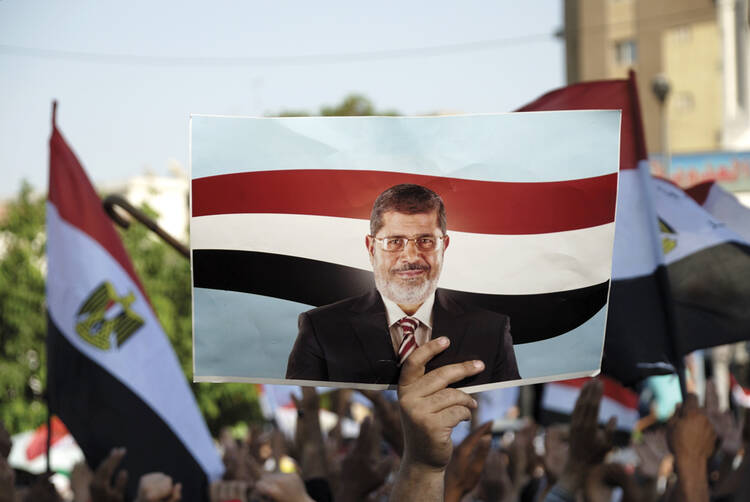

When Mohamed Bouazizi set himself on fire in Tunisia on Dec. 17, 2010, the Arab Spring began. Now, three years later, the results hoped for by people inside and outside the Middle East have clearly not been realized. Iraq is still violently divided between Sunnis, Shiites and an increasingly autonomous Kurdish region. Syria has sunk into a brutal civil war with over 110,000 casualties and 6.25 million citizens displaced to Lebanon, Turkey and Jordan or within Syria itself. Most recently, Egypt’s experiment with democracy has at best been sidetracked. Whether the term coup is appropriate or not, the elected government of Egypt was nonconstitutionally removed by the military. President Mohamed Morsi—regardless of how inept and authoritarian he was—was not removed from office in a democratic fashion. He was removed by the military, albeit a military with considerable popular support. The result has been the emergence of serious divisions within Egypt that could lead to civil war in the most populous and central Arab nation.

Coptic Christians, who were present in Egypt for 600 years before the arrival of Islam, have become the target of choice for religious extremist factions in Egyptian society. Christians were involved in the first demonstrations in Tahrir Square, where shoulder to shoulder with Muslims, they brought down the government of Hosni Mubarak on Feb. 11, 2011. For a moment it seemed that Christians and Muslims could work together for the good of the entire country. If, however, the situation for Christians under the dictatorships of Anwar el-Sadat and Mubarak was not good, it did not improve at all under the democratically elected Mohamed Morsi. A former member of the Muslim Brotherhood, Morsi did little or nothing to improve the lot of his opponents. Although he called himself head of a government “for all Egyptians,” Morsi in fact began to consolidate the power of his own faction, the Muslim Brotherhood. Liberal Muslims, secular Muslims, Christians and even some conservative Muslims felt betrayed and increasingly excluded from the political life of the country.

After large demonstrations in Cairo and around Egypt, Morsi was ultimately removed from office by the military on July 3, 2013. During the television program announcing the removal of President Morsi, the suspension of the Egyptian Constitution and the appointment of Adly Mahmoud Mansour as the interim president, General Abdul-Fattah el-Sisi was flanked by members of the military as well as by Ahmed Muhammad Ahmed el-Tayeb, the grand sheikh of Al-Azhar and Patriarch Tawadros II, the leader of Egypt’s Coptic Orthodox Christians. The image was clear, if strange and unsettling: the Sunni Muslim community through Sheikh el-Tayeb and the Christian community through Patriarch Tawadros, plus large popular demonstrations, supported the removal of President Morsi by the military. Large sectors of the Egyptian population—both Christian and Muslim—as well as some Arab governments continue to support the actions of the military.

Not long afterward, the Muslim Brotherhood responded. Mr. Morsi had been a member of the Brotherhood and advanced its interests for an Islamic Egyptian state. The Brotherhood, which continues to support him, has led large demonstrations around Cairo and in the rest of Egypt. The military has responded to these demonstrations with ferocity. Over 600 Egyptian citizens were killed in one night of clashes between the military and pro-Morsi demonstrators. At the same time, members of the military have been appointed governors in 19 Egyptian states.

Since then, the situation of Christians in post-Morsi Egypt has grown rapidly and significantly worse. Pro-Morsi forces accuse the Coptic Christians of having staged a military coup against the democratically elected president. Although the number of Egyptian Christians is so small (estimates range between 5 percent and 15 percent of the population) that it would, practically speaking, be impossible for them to overthrow the government, nonetheless all over the country violent attacks on Christians and Christian institutions have reached an unprecedented level. On Aug. 17, 2013, a list was published of 32 Christian institutions that had been attacked, looted or destroyed since Mr. Morsi’s removal. When the looting and destruction of Christian homes and businesses are also taken into account, the list is only the proverbial tip of the iceberg. The image of Patriarch Tawadros standing with General el-Sisi has become a rallying point for the pro-Morsi, anti-military demonstrators to focus attacks on Christians as the enemy.

Egypt is experiencing the worst of all possible situations; there is no clear good side and no clear bad side. The actions of the pro-Morsi supporters who attack Christians show quite clearly what their agenda may have been all along. Yet the military’s actions and the ferocity of its response to the pro-Morsi demonstrators make it very difficult to be sympathetic. In fact, that is a major problem: it is almost impossible to be completely sympathetic to either side. Each side has grievances and each side has committed atrocities. This has made it very difficult, if not impossible, for countries like the United States and the member states of the European Union to take a clear stand on what is happening and to support one group against the other.

What About Democracy?

The situation in Egypt highlights a very important fact that is crucial for the entire Middle East. Despite all the rhetoric, democracy alone is not and cannot be the answer. Since the advent of the Arab Spring, there has been a great deal of talk about democracy. Most of it has been shallow and naïve. Westerners in general and Americans in particular are fond of talking about democracy. The United States, for example, invaded Iraq “to set up a democracy.” In addition to being historically naïve, the democracy being spoken about is all too often univocal and one-dimensional. For many in the United States, democracy means “just like us.” Democracy is considered to be identical with the American system without remainder.

Historically, even in the United States the form of democracy changed radically when slavery was abolished in 1863. It was not until the 14th Amendment was ratified five years later that the United States had a definition of what a citizen was, and it was not until the 19th Amendment was ratified in 1920 that women enjoyed full citizenship. Democracy in 21st-century United States is very different from the democracy of the “three-fifths compromise,” which counted five slaves—who had no civil rights—as the equivalent of three citizens for the purpose of congressional representation.

Historically naïve and one-dimensional concepts—to say nothing of expectations—of democracy are not helpful in the Middle East. In fact, they are not very helpful anywhere. No successful democracy arose like Athena from the head of Zeus, fully formed and mature. The history of democracy in Britain, France and Italy, for example, included long periods of development. In some cases the development took centuries. The Magna Carta was signed in 1215, but the English Bill of Rights (for some but not all) was not signed until more than 450 years later, in 1689. After abolishing the monarchy in 1792, France has gone through one Empire and four republics to arrive at its present Fifth Republic. The list goes on. To expect democracy in the Middle East to emerge, develop democratic institutions and thrive in a decade or two is not only unrealistic; it is unfair.

Dictatorship of the Majority

The presidency of Mohamed Morsi proves that democracy alone is not enough. In even moderately pluralistic societies like Egypt, where one faction holds an overwhelming majority, democracy can be the quickest way to a dictatorship of the majority. The majority will always win at the ballot box and can quickly move to disenfranchise minorities. Thus, while there is no doubt that Morsi was democratically elected, there were profound doubts about his agenda for Egyptian minorities, including Christians, secularists and others. Nevertheless, a very dangerous precedent is set when a government is nonconstitutionally removed, especially by the military. The result is that it is almost impossible in the conflict in Egypt to determine who is right and who is wrong. Each side is both right and wrong in different ways at the same time. It is profoundly wrong to attack Christians because they are Christians; but it is also wrong for over 600 demonstrators to be killed. Democratic procedures alone will not solve this.

In observing the turmoil in the Middle East, it has become increasingly clear that if democracy is to succeed, citizenship must be established first. If democracy means no more than “one person one vote” and “majority rules,” it is a formula for the tyranny of the majority. Clearly, in a democracy the majority decides, but it cannot be a zero-sum phenomenon. Minorities do not lose their rights; the opposition is not “excommunicated”; and the possibility remains for the minority to be in power one day. If democracy in the Middle East is to succeed, it must be built on the notion of a citizenry in which, independent of ethnic, religious, political or gender considerations, all are equal before the law in rights and responsibilities.

It is noteworthy how often the word citizen appears in contemporary Christian literature referring to or coming out of the Middle East. The lineamenta for the Synod of Bishops’ meeting in Rome in 2010 used the word several times. On June 23, 2011, the Holy Synod of Antioch (Greek Orthodox Patriarchate) called upon governments to secure “citizens’ interests.” The notion of citizenship in these documents is not determined by ethnicity, linguistic grouping, confessional affiliation or the like.

In the present conflict in Egypt, reference to democracy is a dead end, since in different ways both sides are claiming—neither with overwhelming credibility—to be on the side of democracy. Democracy in Egypt cannot work until a notion of citizenship is enshrined in law and practice. For democracy to succeed in Egypt, all citizens—Muslims, Christians, secularists, moderates as well as the Muslim Brotherhood—must be guaranteed equal rights and obligations before the law.