When Peace Seemed Plausible

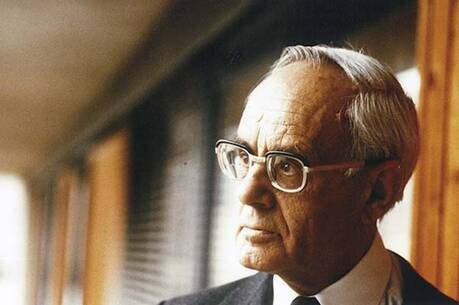

Two decades ago Israel stood on the verge of completing a peace process that promised to end years of fighting with its neighbors and the Palestinians. But the prospect of exchanging land for peace deeply divided Israel into two roughly equal camps pulling in opposite directions—one secular, the other religious. As Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin, who commanded the army that brought Gaza and the West Bank under Israel’s control in the 1967 Six Day War, had the prestige and the commitment in 1993 to implement the Oslo Accords, which promised the Palestinians a measure of self-rule in these occupied territories. But Rabin was killed by an assassin’s bullet two years later, the right-wing Likud party won a close election to choose his successor and the peace process never recovered.

Dan Ephron, who reported on these events 20 years ago, returned to the region in 2010 as Newsweek’s Jerusalem bureau chief. In Killing a King, Ephron presents a compelling portrait of the Rabin era, the last time that peace in Israel seemed plausible. Since then, Rabin’s legacy has largely evaporated, and right-wing and religious parties opposed to ceding territory have attained, according to Ephron, “something akin to a permanent majority.”

Killing a King tells the story on two levels. It is a police procedural that explores the motive and tactics of Yigal Amir, the 25-year-old law student and religious extremist who plotted the assassination for two years and finally shot Rabin on Nov. 4, 1995, after a peace rally in Tel Aviv.

The book is also an analysis of the political firestorm created when Rabin and Yasir Arafat, chief of the Palestine Liberation Organization, shook hands on the White House lawn two years before. In affirming the Oslo process, the two leaders committed to Palestinian rule over Gaza and Jericho, one of seven cities in the West Bank. The agreement also set a goal of Palestinian autonomy in the occupied territories, without addressing how the relentless growth of Jewish settlements would affect the peace process.

By deferring a final agreement until later, the process gave opponents on both sides ample time to mobilize against it. Although a large majority of Israelis supported the agreement when Rabin returned from Washington, Rabin recognized that lone extremists—Palestinian or Israeli—could easily undermine the new relationship and the sense of security for Israelis on which the agreement depended. In fact, violence from Hamas and Israel settlers in the first year of the agreement did just that.

Rabin, described by a U.S. official as the most secular Israeli he had ever met, wrote in 1979 that the settlements were “a cancer on the body of Israeli democracy.” He regarded as obnoxious and reckless the settlers’ view that every inch of the conquered territories was sacred and could never be exchanged for peace.

Like most of the settlers, Amir believed that the agreement was a calamity for Israel and an act of treason by Rabin. Educated at Orthodox schools, Amir absorbed the views that every word of the Torah is divine truth and that Jews “must learn to fathom God’s will” and act accordingly. In this hothouse, messianic atmosphere, he found support for killing Rabin in the Talmudic principle of rodef, which permits a bystander to kill an aggressor who pursues someone with the intent to murder. Under this logic, Amir was the bystander who was compelled to kill Rabin, the rodef, or pursuer, who intended to murder the Jewish people. Emboldened by biblical sanction, Amir and his brother Hagai, an Army-trained munitions and explosive expert, organized a militia, led demonstrations against the peace agreement and eventually decided to kill Rabin.

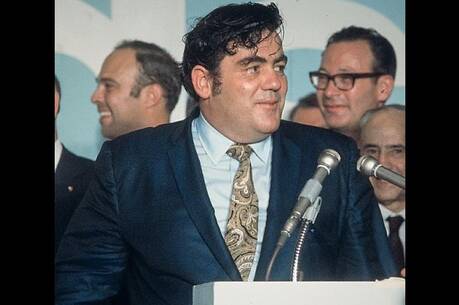

In sober and dispassionate language, Ephron raises the issue of responsibility for Rabin’s death. Benjamin Netanyahu, the leader of the right-wing Likud party (and current prime minister), spoke at rallies where crowds branded Rabin a traitor, a murderer and a Nazi and consorted with rabbis who urged soldiers to disobey evacuation orders. According to Ephron, the ugly invective came not just from the margins, but from the upper echelons of the Likud party. Shabak, Israel’s security agency, feared that physical violence against Rabin was just a matter of time and opportunity. However, as Ephron explains, Shabak made numerous colossal mistakes in its effort to protect Rabin.

In the immediate aftermath of Rabin’s assassination, there was a tremendous wave of sympathy for Rabin and the peace process. Had Shimon Peres, Rabin’s temporary successor, held immediate elections, he would have won and the peace process would have continued. However, in a withering portrait, Ephron shows how Peres bungled badly. Though both Labor Party members, Peres and Rabin had over the years cultivated a deep personal enmity. Rabin regarded Peres as manipulative and a schemer. In delaying elections, Peres wanted to create his own legacy that had nothing to do with Rabin. But as violence continued and Peres’s attempt to forge a new relationship with Syria failed, Israeli voters forgot about Rabin and narrowly elected Netanyahu.

Twenty years later, Netanyahu is again prime minister, the settler movement has doubled in size and influence and the peace process is a distant memory.

This article also appeared in print, under the headline “When Peace Seemed Plausible,” in the February 1, 2016, issue.