A Prince of the Commentariat

The ultra right may have the loudest talking heads these days (Limbaugh, O’Reilly, Hannity, etc.), but the left has cornered the market on stylish, witty, substantial writers (Lewis Lapham, Frank Rich, Maureen Dowd, Hendrik Hertzberg, and others.) None of the leftist gang are likely to become household names, except perhaps comedian Al Franken. On the other hand, the idea that years from now anyone will actually want to read the work of, say, Ann Coulter for its own sake is, um, pretty preposterous. The devilfrom the Falwell-Robertson perspective, anyhowseems to have all the good tunes.

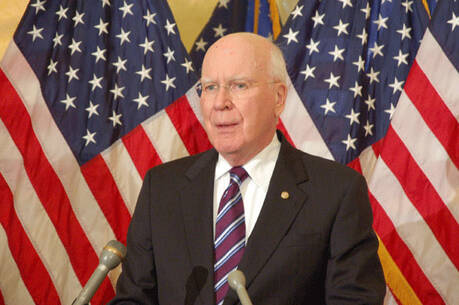

Actually, the genial, smiling face of Hendrik Hertzberg on the book jacket does not look very diabolical; and, as readers familiar with him from The New Yorker’s Talk of the Town section already know, Hertzberg manages to keep a certain buoyancy even in these dark times (for liberals). Still, how could such a smooth-faced fellow already have nearly 40 years of journalism under his belt, as the subtitle maintains? (He graduated from Harvard in 1965.)

Well, there’s a little padding here. The first piece is a rather forgettable unpublished file for Newsweek about the Fillmore ballroom and the San Francisco rock scene in 1966. The book then zips ahead through the 1970’s, and, apart from some good bits about the time Hertzberg spent as a speechwriter for Jimmy Carter, the author doesn’t really hit his stride until the Bush-Clinton-Bush years.

But then, in these roughly 120 pieces surveying the Washington scene, Hertzberg gives a brilliant demonstration of the art of Op-Ed. Wonderfully knowledgeable without being pedantic or flashing his insider’s credentials, intensely moral (and frequently angry) without being prissy or self-righteous, shrewd, funny, precise, he makes the ideal guide to our political past. Summing up John Tower’s failed run for secretary of defense in March, 1989, Hertzberg writes:

The coalition of Republicans and Southerners that has stymied every kind of reform since the end of the New Deal, except during Lyndon Johnson’s first two years, has been fractured. Sam Nunn has got his halo dented, he has learned that he is a Democrat, and he has had the illuminating experience of coming under sustained attack from the right. And the ayatollahs of the Senate’s family values caucus, having spent a week or more defending libertinism, substance abuse, and privacy, have been taught a hard lesson in tolerance. I’ll drink to that, and John Tower is welcome to join me.

Of course, to savor Hertzberg it helps to have been, if not a political junkie, at least a mildly addicted newshound back then. But even if you weren’t, he can fill in the blanks. Gary Hart and Donna Rice, Clarence Thomas and Anita Hill, Michael Dukakis and Poppy Bush, Dan Quayle and Lloyd Bentsen, James Baker and Kathleen Harris, Elián González and Lani Guinierthey’re all here, and hundreds more, in living color. Best of all, perhaps, they are here in a broad historical context. Hertzberg’s reportage is never satisfied with snappy one-liners. Writing about the Senate recently, he notes:

Liberals like the way the Senate derailed President Bush’s plan to turn the Alaska wilderness into an oil patch. Conservatives like the way it thwarted President Clinton’s health-care proposal. But, as these examples suggest, the Senate is essentially a graveyard. Its record, especially over the past century and a half, makes disheartening reading. A partial list of the measures that have been done to death in the Senate would include bills to authorize federal action against the disenfranchisement of blacks, to ban violence against strikers by private police forces, to punish lynching, to lower tariffs, to extend relief to the unemployed, to outlaw the poll tax, to provide aid to education, and (under Presidents Truman, Nixon, and Carter as well as Clinton) to provide something like the kind of health coverage that is standard in the rest of the developed world.

Well, given a body that has included such dubious figures as Theodore Bilbo, Pat McCarran, Joseph McCarthy, Strom Thurmond and Jesse Helms, that might seem to be a safe, if seldom heard, judgment. But Hertzberg is not content with whacking away at senatorial (congressional-presidential-public) knaves and fools. He actually has a serious proposal for curing some of the worst ills afflicting the American body politicnamely, proportional representation. And he started preaching it long before the Electoral College fiasco of 2000.

The mess is obvious, but nobody addresses it: 98 percent or more of incumbents get elected regardless of their performance. A bare majority (at best) of eligible voters bother to vote because, in fact, most elections are no contests at all. In 2004 Americans living outside the few closely contested states saw no ads for either Bush or Kerry throughout the campaign: they were taken for granted.

Candidates had no interest in anybody but the undecideds; and in the end, as usual, vast portions of the electorate went under- or un-represented (African-Americans make up about 13 percent of the population, but have only one senator; not to mention women or Hispanics). All politics may be local, but when a country as mobile and uprooted as ours does all its voting on a (crudely gerrymandered) regional basis, the results are absurd.

The solutionalready used in much of the rest of the worldinvolves some complicated math, as devised by a 19th-century British M.P., Thomas Hare. But it basically comes down to dropping the silly bare-plurality system in favor of a method that would put into office both local favorites and at-large, widely supported, second-place finishers. Hertzberg eloquently explains and defends his 27th Amendment, though he is realistic enough to admit that in the present-day climate of ahistorical, quasi-religious worship of the Constitution it does not stand much of a chance.

At any rate, on these and related issues Hendrik Hertzberg writes with such logical force and personal zest that even the competition (more or less sensible conservatives like George Will and David Brooks) shouldif there’s any justicetip their hats. The man is a prince.

This article also appeared in print, under the headline “A Prince of the Commentariat,” in the February 21, 2005, issue.