Kerry James Marshall (b. 1955) has a vocation within a vocation. For 30 years he has worked to fill a gaping hole in the Western art tradition, a virtual absence of black people featured in the works on the walls of museums. As cultural arbiters, museum curators determine not only what is (and is not) beautiful but which art is (and is not) important and worthy of being shown. The absence of black artists and figures in most museums is one more example of how, and to some extent why, black lives have been overlooked for centuries. That is precisely Marshall’s point. To correct the problem, he has spent his life making black life visible through excellent painting. It is a tremendous achievement that edifies us all.

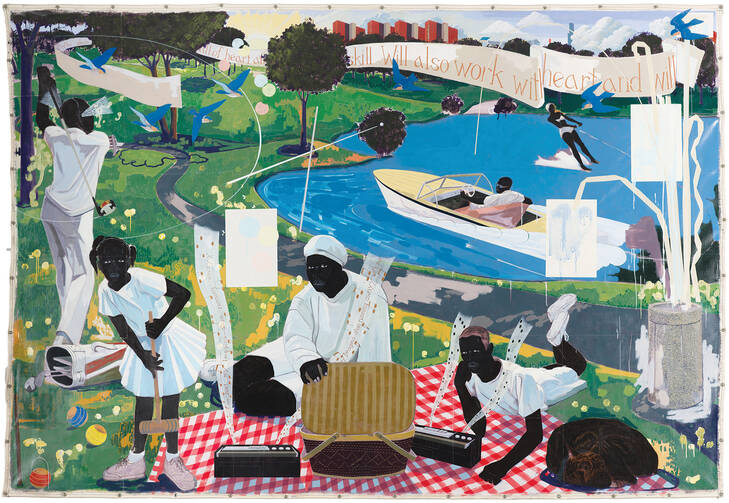

“Kerry James Marshall: Mastry” is a ravishingly beautiful art show that can stir the emotions and challenge thinking. This retrospective by a living artist fills two floors of the Met Breuer Museum in New York City. The exhibition, mostly paintings, is beautiful simply because Marshall’s colors, techniques and compositions are masterful. But the main reason to go is to see how Marshall, who is black, depicts the lives and experiences of ordinary black Americans—to see how he paints childhood, family, neighborhoods, romantic love and courtship, Black Power, the civil rights movement, death and mourning. You will also find a small pantheon of black heroes or secular saints, some with halos. (The artist’s education at a Catholic grammar school is evident in these and other early works.) We see Marshall’s personal viewpoint on canvas, of course. But given the racial tensions voiced during this year’s presidential race, the violence that prompted the Black Lives Matter movement and the continuing confrontations between black Americans and police around the nation, Marshall’s perspective could not be timelier.

After graduating from Otis Art Institute in 1978, Marshall taught art in Los Angeles and Chicago. He has received a number of awards and residencies, including a MacArthur fellowship in 1997. His work has been shown throughout the United States and in Italy and Germany. As an educator, he continues to work on a graphic novel and animated film called “Rythm Mastr,” the idiosyncratic spelling from which the exhibition’s title is derived. These are part of his ongoing outreach to young people.

Distinctively, Marshall paints black people using black paint, without tints. The artist also uses highly saturated complementary colors (red/green, blue/orange) and sometimes bold patterns on clothing and in backgrounds to further heighten the color contrast. Conversely, in two or three works, Marshall paints a black person on a black background, as if daring viewers to look long enough to find the subject. This takes effort and time. As every great artist does, Marshall shows the viewer exactly where to look.

Marshall also works on what he calls “the grand scale.” In art history, size often conveys importance. An epic battle scene, a royal coronation or a miracle of Jesus may demand a large canvas. Jacques-Louis David’s painting “The Coronation of Napoleon” (1807) is 32 feet wide. Marshall’s painting of people at a local barbershop (“De Style” 1993) is over 10 feet wide. What many would consider a quotidian event, Marshall deems important.

He also treats events of historical magnitude—slavery, lynchings and the civil rights movement that marked his generation. Marshall’s family was living in Birmingham, Ala., in 1963 when four girls were killed there by a bomb detonated in a Baptist church. They moved to the Watts area of Los Angeles when Marshall was 9 years old, just before race riots torched much of the neighborhood in 1965, leaving 34 dead and 1,000 injured. His family lived in Nickerson Gardens, a low-income housing project the artist depicted in “The Garden Project,” a series of paintings. In “Watts 1963,” three children play on green grass under palms, a blue sky and sunshine. An overhead banner promises “more of everything.” Yet the artist visually communicates that the utopian promise falls short. Note the children’s serious expressions, the fetal position one boy takes and the opaque drips and surface smears that deface the landscape.

While many of Marshall’s works are deeply affecting, “The Lost Boys” (1993) moved me to tears. Here the artist memorializes the deaths of two children. A larger-than-life-size boy sits in a toy car, the kind you put a coin in to have a quick ride in place. The second boy recalls a real-life child killed by police in his home while holding a water pistol they mistook for a gun. In the artwork, the child holds a pink pistol, obviously a toy. Nearby, the trunk of a Tree of Life is beset by serpentine yellow tape: “Police line, do not cross,” it reads. The dates bracket summer vacation, Marshall told the literary editor Charles Rowell in an interview, when children “spend the most time simply being children and playing and experiencing things without a lot of structure around them.”

A great retrospective like “Mastry” offers an entire body of work developed over time. It shows well how Marshall simplified and distilled his work after 2000. As contemporary museums expand their holdings by black artists, Marshall and his peers—Carrie Mae Weems, Kehinde Wiley, Kara Walker, Mickalene Thomas and others whose images reflect black experience—enable others to see what they have been missing.

“Mastry,” first shown in Chicago at the Museum of Contemporary Art, is on view at The Met Breuer in New York City through Jan. 29. After that it travels to the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles.