The Catholic Worker is part of my life, at least on Mondays when I stop by Maryhouse for a bite to eat and Evening Prayer after saying Mass around the corner at my former parish, Nativity. But on Thursday, May 1, I was also in that neighborhood of Manhattan’s Lower East Side at the other Worker house, St. Joseph’s, two blocks away. A special Mass and celebration there marked the Catholic Worker’s 75th year. On that date in 1933, Dorothy Day, Peter Maurin and others walked up to Union Square, a rallying place for political protests, to sell the first copies of The Catholic Worker newspaper. The very fact that the stated aim of the Catholic Worker movement is “to live in accordance with the justice and charity of Jesus Christ” stands out as an implicit protest against the injustices of a world beset by violence and greed. As Dorothy Day herself once said, “God meant things to be much easier than we have made them”—especially as we have made them for the poor and marginalized.

Catholic Worker houses of hospitality are spread throughout the country and abroad, but it is those two on the Lower East Side that I know best, though I have also visited the Worker farm north of New York City. In the 1970s, during my first stint in New York, I remember seeing Dorothy Day at Mass at Nativity; and I still recall where she sat, a dignified figure dressed in whatever the Workers’ clothing room had to offer. A friend, referring to her as a living saint, had by then led me to her autobiography, The Long Loneliness. But it was only through visiting the two houses on the Lower East Side that I came to have a sense of what a Catholic Worker house is actually like.

When I knock on the Maryhouse door on Mondays and walk down into the large dining room, I see a varied group of people, some healthy and strong, but most frail in body or mind or both—the very mix of people with whom Jesus might have spent time. The home-cooked dinner has arrived by then from St. Joseph House, in a rumbling shopping cart pushed by the famous Eugene. At the end of the Maryhouse dining room is a small table presided over by Evelyn, a longtime resident who immigrated from Haiti decades ago. Her table is something of a gathering site and my favorite spot for supper.

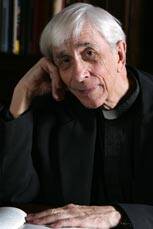

Afterward I climb to the third floor with Communion for Frank Donovan and Ed Forand, 90 and 91 years old respectively, who worked closely with Dorothy Day. Frank, in fact, lives in the very room in which she spent the final years before her death in 1980. Her desk and other furnishings are still there, though her papers are now in a special collection at Marquette University. After those visits, it’s back to Evelyn’s table in the dining room for Evening Prayer.

Very old prayer books emerge from the nearby china closet, along with a candle for the center of the table. Once Evelyn has set the ribbons in their proper places (or scraps of paper if ribbons have disintegrated), she divides the people around the table into two groups, so that they can recite psalms antiphonally. When we reach the petitions, we offer many for ill or struggling people, and usually one “for an end to this dreadful war in Iraq.” We end with a prayer penciled into the backs of the books that begins, “May the Lord bless us, protect us from all evil and bring us to everlasting life.” A useful prayer with which to end the day.

The ministry at both houses—in its personal care for the frail and in its advocacy for Gospel nonviolence—stands out as a needed sign of contradiction in a once poor but now gentrified area that nevertheless still attracts many poor and homeless people in need of basic assistance. Dorothy Day herself contributed articles to America in the 1930s on the struggles of poor people, and near the altar for that May 1 Mass was the same steel serving table in front of the ovens where she herself often stood. Over the years, thousands have received nourishment in that room, both physical food and the bread of life whenever Mass is celebrated, as it was that night.

In 2000 the late Cardinal John O’Connor of New York introduced the cause for Dorothy Day’s beatification, and with that initial step she became known as Servant of God. But throughout her adult life of ministering to the poor and going to jail for just causes, she had long since earned that title many times over.