Despite the music coming from our high school band, one could hear the red hot candies hit the bells of the tubas. Sometimes, with so much force that they’d bounce off. But others went right down the neck, producing a cheer in the trombone section, from where they had been launched.

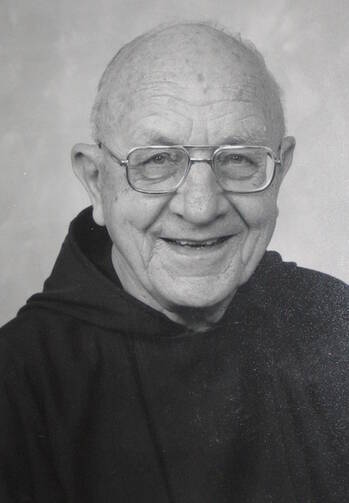

Everybody could hear and see them, everyone except Father Tim. By the early ’70s, with still a decade of teaching to go, Father Timothy Gottschalk would have been well into his 60s. Born in 1906, he had entered the Capuchin Franciscans in 1927 and would teach 50 years at our high school. He taught a lot of subjects: music, Latin, English, German, religion and history. He was also a gifted artist, painting a beautiful, contemporary Last Supper, which still adorns Thomas More Prep’s dining hall, and a San Damiano Cross for the friars’ chapel.

But to us, back in ’72, he was just old Father Tim, the band teacher who was losing his hearing and much of his sight. No one was trying to be mean to Father Tim. That was the point. He didn’t even know it was happening. It was the last hour of the day, in a much disciplined Catholic school. It was also a class in which we were joined by the girls from nearby Marian High School. Just seemed like a time to loosen up and let go. Tom Lippert climbed out the window during one rehearsal. Father Tim did notice him coming back in, through the door, and—really very kindly—asked him not to be tardy.

Obviously, I remember this with regret, though the worse that I did, in the saxophone section, and at Mark Wiesner’s goading, was to stand and play our instruments, unasked and unobserved by Father Tim. But admiration for Father Tim as a man runs deeper than remorse for our adolescent inanity. Day by day, year by year, he gave himself over to something greater than himself, and that’s the deepest meaning of what it means to be a human. We can’t be ourselves, be what God intended, without going out of ourselves in service to others.

A man or woman, who simply sucks the world into his or her own self, shrivels the soul, no matter how much of the world it swallows. It is when the self is poured out that it grows.

Our deepest identities are found in our call to service. We serve the Lord by serving others, and, in doing so, we find ourselves.

John the Baptist yields to the Christ, and Jesus surrenders to the Father by embracing his mission, by giving himself over to the people as their suffering messiah. We become ourselves, the selves we were meant to be, when we serve. It is one way in which our souls mirror the utter fruitfulness of God: The more we pour out ourselves, the more we become our best selves.

When St. Paul turned the secular Greek word apóstelos (herald) into a religious vocation—“Paul, called to be an apostle of Christ Jesus by the will of God”—he recognized that his own deepest identity came with a call, from God, to serve others, as herald to the people.

This isn’t a little lesson about priestly service, though Father Tim was a priest and faithfully served as one. One could just as easily speak of the grandmother, raising her grandchildren, or even of the store clerk, trying to be kind to the impatient customers.

Would that we kids could see what Father Tim was truly doing there, in that band room, that he was pouring out himself in imitation of Christ and his saints. But then he didn’t do it so that we would note it. Like any other Christian soul, he was answering the call to serve, and, in being a servant, he was finding both his salvation and himself.

Readings:Isaiah 49: 3, 5-6 1 Corinthians 1: 1-3 John 1: 29-34