Iowa holds its presidential caucuses on the evening of Monday, Feb. 1, finally giving us a clue as to whether Donald Trump is a movement or a mirage—and whether Hillary Clinton can secure the Democratic nomination while the Republicans are still fighting, or face a long primary season against Bernie Sanders. The candidates’ respective strengths in Iowa—in urban versus rural areas, or in counties with Catholic versus Protestant pluralities—may set a pattern for future contests in the nomination process.

The mid-sized state, one of the few remaining general-election battlegrounds in a highly polarized nation, is more politically diverse than its stereotype as an all-white collection of farming communities would suggest. The maps below detail the different voting histories of Iowa’s 99 counties and what they mean for the candidates in 2016.

THE DEMOGRAPHICS

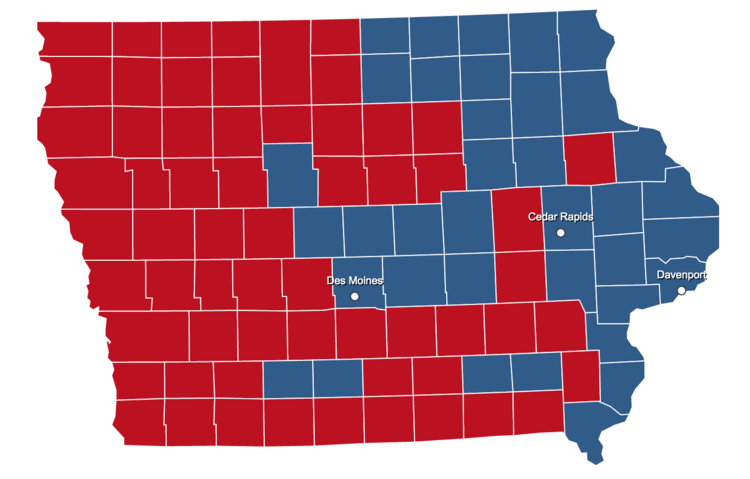

Iowa gained about 78,000 residents from 2010 to 2014, according to Census Bureau estimates, but growth was concentrated in a few counties. Three counties gained at least 10,000 residents each: Polk (Des Moines), Dallas (also in the Des Moines metro area) and Johnson (Iowa City, where the University of Iowa is located). But 69 of the state’s 99 counties lost population, continuing a decades-long exodus from rural counties in the Farm Belt. Population losses generally reflect native residents moving out, but the counties in dark red on the map above are in especially dire demographic straits: they saw more deaths than births in the first four years of this decade. Keep this geographic pattern in mind; the Des Moines area, Johnson County and counties along the Mississippi River have often voted differently from the rest of the state in recent elections. In 2016, will the “loser” counties (using the word in a demographic sense) break for Donald Trump and other anti-establishment candidates?

Notice Buena Vista County, surrounded by red in the northwest interior of the state. It has avoided population loss because of a large immigration population, drawn by the meat-packing and other food-processing industries. Buena Vista is now 19 percent foreign-born, the highest in the state and one of only four counties where the foreign-born population tops 10 percent. (Crawford, Jefferson and Marshall are the others, all in the minority of rural counties that have avoided population loss.) Will the strong anti-immigration rhetoric of Trump, Cruz and other Republican candidates play well in the pockets of Iowa with sizable foreign-born populations, or will such candidates do best where immigrants have not offset an exodus by native Iowans?

THE DEMOCRATS

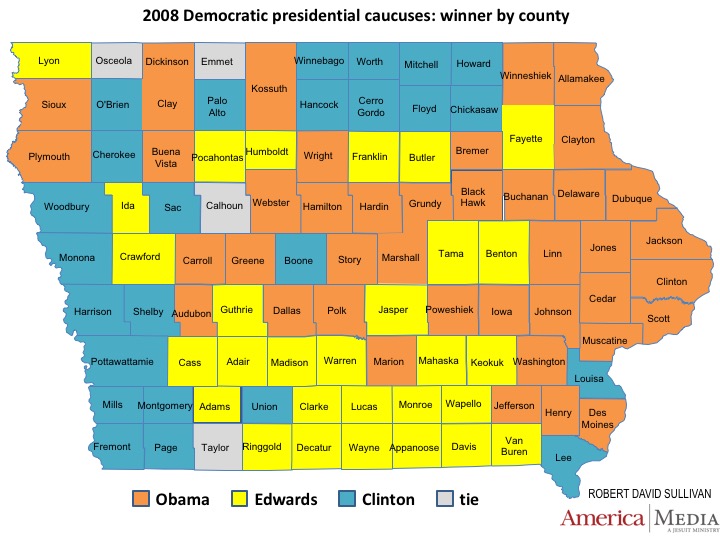

The 2008 Democratic caucuses produced close to a three-way tie, with Barack Obama winning 34.9 percent of the delegates chosen to attend county conventions, John Edwards winning 31.2 percent and Hillary Clinton getting 30.4 percent. The map above suggests a military battle, with Obama forces pushing in from Illinois in the east, the Edwards army advancing from the south central border and Clinton relegated to the margins in the north and west. (The advantage of coming from a state bordering Iowa or New Hampshire is often downplayed, as it makes those states seem less pure and less deserving of voting first every four years.) Obama got a majority in just one county: Johnson, home to Iowa City and the University of Iowa. But his 39 percent in Polk County (Des Moines) gave him his biggest margin and probably put the state out of reach for his competitors.

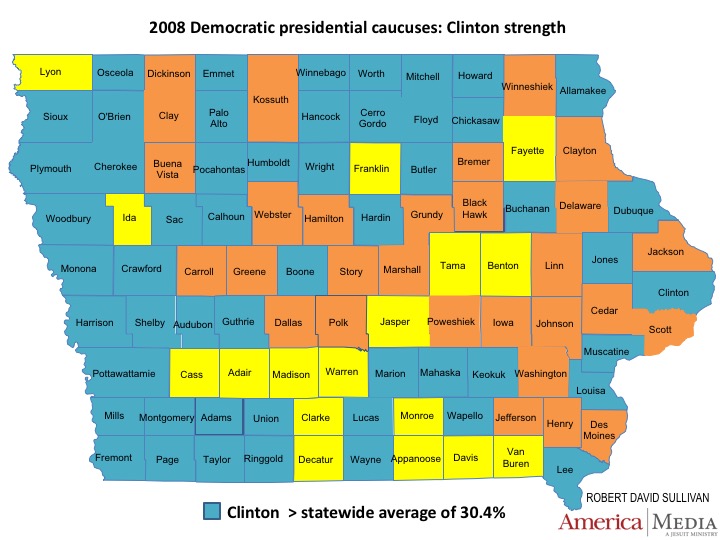

In 2016, Hillary Clinton will need close to a majority to win Iowa against a single strong opponent, Bernie Sanders. This map shows one route to victory, based on the assumption that her best counties in 2008 will be her best counties again this time—or that she gets roughly half of both the Barack Obama vote and the John Edwards vote from last time. In 2008, the biggest county where Clinton got more than 40 percent was Pottawatamie, on the Nebraska border and part of the Omaha metropolitan area. Under this map’s scenario, she would have to steal Dubuque County (a center of Iowa’s Catholic population) from the Obama column and Wapello County (home of Ottumwa, the “Video Game Capital of the World”) from the Edwards column. Conversely, Bernie Sanders could prevail if he gets big majorities where Clinton ran weakest last time—if he can combine the Obama base in college towns and in the Des Moines area with the Edwards base in the more rural counties in the south.

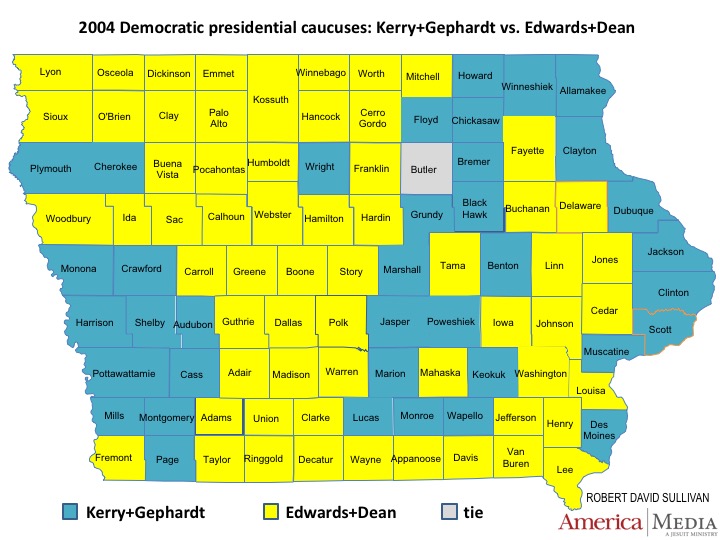

Another possible regional breakdown can be seen in the results of the 2004 Democratic caucuses, when Howard Dean’s vaunted campaign organization was overtaken by John Edwards in the populist/outsider lane. Dean ended up carrying only four smaller counties, though he got at least 25 percent in several urban centers, including Woodbury (Sioux City), Johnson (Iowa City) and Muscatine (part of the Davenport metro area). This wouldn’t be much of a base for Bernie Sanders in a two-person race, so he would need to do well in the 48 counties, mostly smaller, won by John Edwards. Combined, Edwards and Dean won 49.9 percent of the delegates in 2008, beating the combined total for John Kerry and Richard Gephardt in the counties colored yellow. Kerry and Gephardt won a combined 48.3 percent, dominating the urban areas of Pottawattamie, Scott (Davenport), Dubuque and Wapello counties. If there’s a Sanders surge, Hillary Clinton may need the river counties to save her.

THE REPUBLICANS

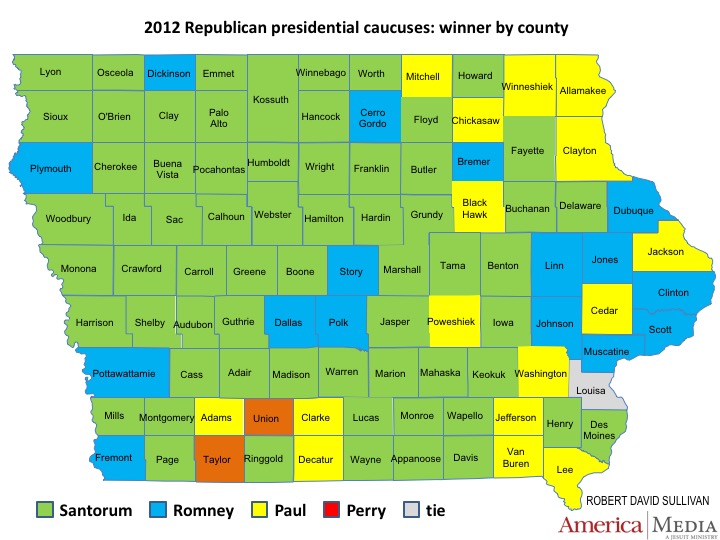

In 2012, the Iowa Republican caucuses were so close that Mitt Romney was declared the winner before a recalculation of the results gave Rick Santorum a victory margin of just 34 votes in the state’s nonbinding straw poll. (The caucuses also chose delegates to county conventions, but they were not required to declare allegiance to specific candidates.) Santorum got 24.54 percent of the 121,590 votes cast, with Romney getting 24.51 percent, Ron Paul getting 21.41 percent, Newt Gingrich at 13.29 percent and Rick Perry at 10.33. That Santorum won by such a narrow margin despite carrying 65 of the state’s 99 counties shows how much his support was concentrated in more rural parts of the state. Still, he wouldn’t have won without the 644-vote margin, his biggest in the state, in Sioux County in the northwest corner of Iowa. Sioux County is not even in the 20 most populous counties in the state, but it has a huge influence in the caucuses because its electorate is so Republican (Romney got 83 percent here against Obama) and has recently broken overwhelmingly for a single candidate—Santorum in 2012 and Mike Huckabee in 2008. This year Ted Cruz is counting on a big win in the northwest to offset any weaknesses in Polk County (Des Moines) and the urban centers along the eastern border, the places that once gave an advantage to more moderate candidates.

Rick Santorum’s 2012 win was paper-thin, but he was competing with other candidates for the socially conservative vote. Santorum, Newt Gingrich, Rick Perry and Michele Bachmann all tried to win evangelical voters, and together they got 53.1 percent of the straw-poll vote. The rest was split between mainstream conservative Mitt Romney and libertarian Ron Paul. The “moderate” vote—or the unlikely combination of hawkish Romney and isolationist Paul—was greater than the social conservative vote only in Polk County (Des Moines) and Story County (Ames) in the middle of the state, along with most of the college towns and riverfront cities in the east. This question for 2016 is whether Donald Trump can stitch together enough votes in these areas to offset the big margins Cruz is expecting elsewhere.

A 2010 survey calculated the largest religious denomination in every county in the United States, based on self-reported congregation data from 236 religious groups. Iowa is at something of a crossroads: to the east, Wisconsin and the top half of Illinois are Catholic; to the south, Missouri is Southern Baptist; and to the north, rural Minnesota is Lutheran. Iowa, like Nebraska to the west, is more of a patchwork, with different religious groups claiming the most members in different counties. Though the evangelical movement is most often identified with Southern Baptists, candidates favored by that religious group have also done well in the parts of Iowa where Methodists and, more so, evangelical Lutherans dominate. Interestingly, support for Rick Santorum, a Catholic candidate, did not line up with “Catholic counties” in 2012. He lost the four biggest counties with Catholic pluralities (Polk, Linn, Scott, Black Hawk and Johnson, all in the central or eastern part of the state) but did take the fifth largest (Woodbury, in the west).

Source: Clifford Grammich, Kirk Hadaway, Richard Houseal, Dale E. Jones, Alexei Krindatch, Richie Stanley and Richard H. Taylor. 2012.2010 U.S. Religion Census: Religious Congregations & Membership Study. Association of Statisticians of American Religious Bodies.

Donald Trump is often compared to Pat Buchanan, another political neophyte who competed for the “anger” vote in the GOP nomination contest. Buchanan finished a strong second in Iowa in 1996, getting 23.3 percent of the vote. This map shows where Buchanan got at least 25 percent of the vote, providing another possible road map for a Trump victory. Like Rick Santorum, Buchanan was a Catholic who lost most of the larger Catholic counties, but he did win Dubuque in addition to most of the western Catholic counties. He also won the Evangelical Lutheran corner in in the northwest. If Trump can do the same, he’s well on his way to beating Ted Cruz in Iowa.

One of the mysteries of the 2016 GOP race is: Whatever happened to the Ron Paul vote? Paul was a competiive third to Rick Santorum and Mitt Romney in Iowa last time, getting 21.4 percent, and he was a strong second in New Hampshire, with 22.9 percent. Yet his son, Rand Paul, has stayed below 5 percent in national and in Iowa polls this time, and none of the other candidates are making a play for the so-called libertarian vote. On the contrary, all have bellicose views on foreign policy (splitting only on whether to invade or merely bomb other countries) and strictly law-and-order approaches to criminal justice. So where do Ron Paul’s 2012 supporters go? As this map shows, they were concentrated in college counties (Story, Johnson), a few counties along the Mississippi (including Dubuque), and a few rural counties to the south. These are areas where Cruz is expected to be weakest, so will Trump get the libertarian vote by default?

A long, long time ago, the Iowa caucuses were part of the moderate base of the GOP, giving victories to Gerald Ford over Ronald Reagan in 1976, George H.W. Bush over Reagan in 1980, and establishment favorite Bob Dole in 1988 and 1996. The moderate vote seems to have almost disappeared. In 2008, eventual nominee John McCain and Rudy Giuliani were considered the most centrist candidates, and neither put much resources into Iowa. Together they cracked 20 percent in only a handful of counties, notably Johnson (Iowa City), Dubuque, and Scott (Davenport). The question for 2016 is whether they can give much of a boost to whoever passes as a moderate this time around (Marco Rubio?).

Here’s how much Iowa has changed in 20 years. In 1996, all but the white counties in this map went for either ultimate congressional insider Bob Dole or for Southern moderate Lamar Alexander. (The rest went for Pat Buchanan.) In 2012, Mitt Romney was the closest to a moderate, though he still campaigned as a stranger to Washington, and he lost the great majority of Dole counties. The moderate coaltion seems to have vanished with the turn of the century.