A Little Thing

If the Gospel accounts stopped just after Jesus’ entry into Jerusalem on Palm Sunday, how would you imagine the next few days playing out? The Gospel of John quotes Zec 9:9–10 as Jesus enters the city: “Look, your king is coming, sitting on a donkey’s colt!” The people were taking “branches of palm trees” and going “out to meet him, shouting, ‘Hosanna! Blessed is the one who comes in the name of the Lord—the King of Israel!’” The scene could easily be imagined as a hero’s entry in advance of his great triumph soon to follow.

When Jesus entered Jerusalem, his disciples must have felt the same weight of expectations, the portent of what Jesus’ entry meant, not just for themselves, but for everyone. If Jesus was the promised Messiah, the events to come were not just concerned with the realities of one Passover in Jerusalem or the fate of the people of Judah but with the world and, yes, the world to come. What could one do but wait with sharp expectancy for the world-historical events to unfold?

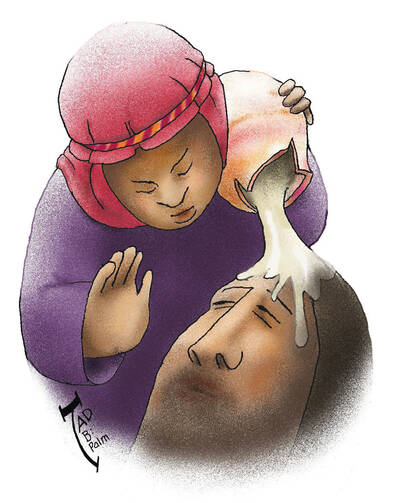

And yet one unnamed woman does more than wait. Her actions interpret not only Jesus’ entry as the expected king but the sort of king Jesus must be. After his entrance into Jerusalem, Jesus went to Bethany. In Bethany, “a woman came with an alabaster jar of very costly ointment of nard, and she broke open the jar and poured the ointment on his head.” In this action, she simply supports the reception accorded Jesus as he entered Jerusalem as the king. The mashiach (Greek christos) is the “anointed one,” and her actions tell us that she not only understands that Jesus is the anointed one but that she has a need or responsibility to anoint him. But who is she to anoint a king?

The people gathered around Jesus, however, ask a different question: “‘Why was the ointment wasted in this way? For this ointment could have been sold for more than 300 denarii, and the money given to the poor.’ And they scolded her.” Their question is not without merit, for in scolding her they probably were attempting to voice Jesus’ concern for the poor seen throughout his ministry. Jesus asks another question, “Let her alone; why do you trouble her?”

Somehow the concerned disciples have missed something. “She has performed a good service for me. For you always have the poor with you, and you can show kindness to them whenever you wish; but you will not always have me.” Jesus’ response is not an attempt to mark out the permanence of poverty as a social problem but to note that her “good service for me” has focused proper attention on him. Whether or not she knows the full implications of what she has done, she has directed those present to see Jesus as the Messiah, to grasp his Christological identity.

Her identification of Jesus as the Christ by anointing went deeper, however, than even she knew, for she could not have known that she had also anointed Jesus’ body “beforehand for its burial.” Faithful women will later seek to care for Jesus’ broken body after his death in order to anoint it with burial spices, but they would not find a body. The unnamed woman, though, already had anointed Jesus not only as a king but as the humble king who emptied himself out in death.

The humility of Jesus is reflected by the generosity of this woman, who pours out all that she has as a witness for him. Who is she to anoint a king? Given the universal significance of Jesus’ Passion week, her anointing might seem a little thing, but it is the most any of us can do: she recognizes Jesus, and gives all she has for him, not understanding completely that her actions helped to prepare the king, first for his death and then for his triumph, but knowing somehow he is the Messiah.

The significance of her actions is felt when Jesus says, “Truly I tell you, wherever the good news is proclaimed in the whole world, what she has done will be told in remembrance of her.” We, too, are called to recognize Jesus the Messiah in faith, not simply as a conquering hero but as a servant willing to give himself up to death for us.

This article also appeared in print, under the headline “A Little Thing,” in the March 23, 2015, issue.