Writing in yesterday's Los Angeles Times, philosophy professor Eric Schwitzgebel urges something of an aggiornamento in the way philosophers practice their craft.

Noting "the historical contingency of the journal article, a late-19th century invention," Schwitzgebel urges his colleagues to publish in platforms that connect with more people and a broader array of human concerns. In Schwitzgebel's words: "Too exclusive a focus on technical journal articles excludes non-academics from the dialogue — or maybe, better said, excludes us philosophers from non-academics' more important dialogue."

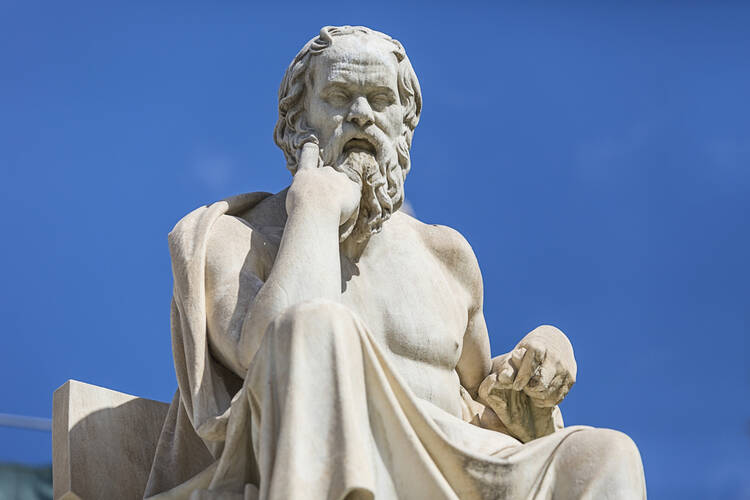

"Popular essays, fictions, aphorisms, dialogues, autobiographical reflections and personal letters have historically played a central role in philosophy," writes Schwitzgebel. "So also have public acts of direct confrontation with the structures of one's society: Socrates' trial and acceptance of the hemlock; Confucius' inspiring personal correctness."

Schwitzgebel has a pronounced confidence in the possibilities of social media and other 21st century mediums:

A conversation in social media, if good participants bring their best to the enterprise, has the potential to be a philosophical creation of the highest order, with a depth and breadth beyond the capacity of any individual philosopher to create. A video game could illuminate, critique and advance a vision of worthwhile living, deploying sight, hearing, emotion and personal narrative as well as (why not?) traditional verbal exposition — and it could potentially do so with all the freshness of thinking, all the transformative power and all the expository rigor of Hume, Kant or Nietzsche.

I'm not sure I share his confidence in social media (I've seen too many Facebook conversations liquefy into anger), but I appreciate his desire to make philosophy a more relevant, engaging enterprise. This is precisely why I majored in it: philosophy spoke to fundamental human concerns and gave me the intellectual resources to begin to make sense of existence. But I had the privilege to study the subject at a Jesuit university (Saint Louis University), where the big questions -- Do we have free will? Can God's existence be proved? What is happiness? -- were central to the curriculum. Not all philosophy departments are like that, and Schwitzgebel has done a service by reminding readers of philosophy's breadth and its possibilities for animating essential conversations.

See here for his full op-ed.