Sometimes the most important line of a conversation comes after it’s concluded, when you’ve already moved from substance to trivialities. Not long ago, I was walking with a woman toward the door of a funeral home, where her family had been making arrangements. As we got ready to part, she said, “I do believe in the resurrection, but it’s so hard to picture an afterlife.”

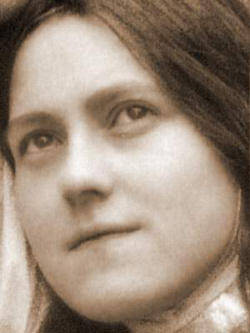

I agreed. Her comment reminded me of a passage from Story of a Soul, the autobiography of Saint Thérèse of Lisieux. Here’s how, in her journal, the young Carmelite nun described the relationship of this world to the next.

It’s a darn good description, though it didn’t dispel the darkness in which faith must mature. The saints themselves struggled with faith because faith isn’t something that grows a long distance from doubt. The two, faith and doubt, twine together throughout our lives. We’re asked to surrender ourselves to something we cannot truly picture, and that isn’t easy.

Thérèse had a beautiful image of the afterlife, yet, in the face of her own death, the young Carmelite fought, as we do, to sustain that picture in her imagination. She wrote:

And then Thérèse records the very thought that mocked her faith, as she approached her own death from tuberculosis.

In Dives and Lazarus, the parable of the poor man who goes to heaven, Jesus asks us to envision the afterlife. Doesn’t he realize how hard that is for us to do? Our imaginations are too shallow, too inept for the task. How can anything as pathetic as the pictures of paradise, which we summon up on earth, inspire us to live and to die in the Lord?

Honestly? They do fall short, because the human mind is not equipped to deal with utter novelty. And, whatever else the afterlife is, it is surely that, absolutely novel.

Indeed, the very spirit of our age, a pseudo-scientism, no longer believes in novelty, in something truly beyond our ken, something deeper than our imaginations. We know that there are things not yet comprehended by science, but it is almost impossible for us to imagine realities lying forever beyond the reach of science, realities truly novel in our world, because they are not of this world. Yet utter, unimaginable novelty came into the world with Christ, and we will be called into that adumbral novelty at death.

The parable of Dives and Lazarus does not draw us a picture of heaven. That is not something the human mind can receive on this side of the grave. But Christ does tell us what matters about the afterlife, what determines our destinies. Joy in the next life depends upon justice in this one.

As always, we would like to see for ourselves, make our own judgements and preparations. But we don’t—we can’t—judge the utterly unimaginable. To the contrary, Christ tells us that it is we who will be judged by it.

Amos 6: 1a, 4-7 1 Timothy 6: 11-16 Luke 16: 19-31