Ireland in the 1980s, a young Father Odran Yates can’t contain the respect, which his clerical collar garners. Boarding a train, walking through all of its cars, he resigns himself to standing near the door.

John Boyne’s novel, A History of Loneliness(2015) is a story of the clerical sexual abuse crisis. Father Yates isn’t guilty of the crime, but his priesthood pays a heavy price for it. Respect evaporates; he is later maligned and maltreated by law officials when he sincerely, if ineptly, tries to help a lost child.

We call a priest, “father,” a term of respect, offered to one who gives life itself, whether biological or spiritual, but now the title flounders a bit on the tongue. For several decades, the priesthood and paternity have been on parallel tracks of decline. Sadly, church leaders must largely blame themselves for the erosion of their moral authority, but patriarchy of every sort has been on the wane in Western societies.

Father Knows Best was both a title and a theme of 1950s television. But contrast Robert Young’s Jim Anderson with the blustering buffoon that Bill Crosby played in the 1980s. Doctor Cliff Huxtable became a template for subsequent fathers on television commercials. Mom and all the kids are smarter than Dad. Why should he choose the family calling plan?

Does the Bible support patriarchy? God seems to chide Job for questioning his authority:

Yet no one’s paternity is less assertive than God’s. God is so gentle in divine authority—urging us to choose the good in love rather than compelling our response—that many have come to doubt the very existence of the deity.

St. Mark presents a Christ who calms the storm, filling his disciples with awe. They ask, “Who then is this whom even wind and sea obey?” (4:41) Yet this same Jesus will open himself on the wood of the cross, dying with such self-emptying love that the Roman Centurion, an outsider who watches, will confess, “Truly this man was the Son of God” (15:39).

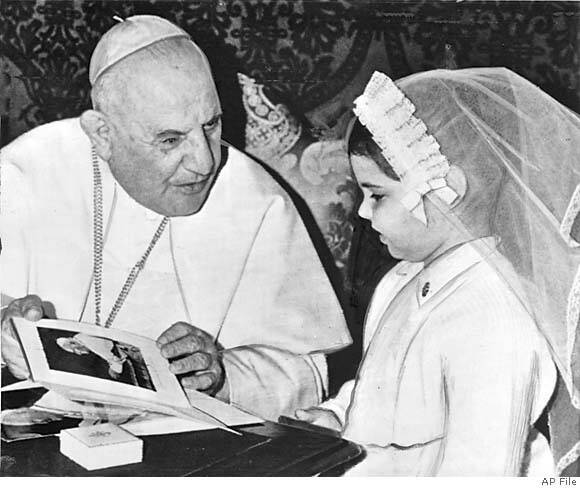

Priests, bishops and the fathers of families are still needed to guide and to govern, but they mustn’t assume a divinely sanctioned arbitrariness. God doesn’t govern that way. How can man? Opening the Second Vatican Council, Pope John XXIII sought to wean a new generation from the arbitrariness of past patriarchs. “Nowadays however, the Spouse of Christ prefers to make use of the medicine of mercy rather than that of severity. She considers that she meets the needs of the present day by demonstrating the validity of her teaching rather than by condemnations” (“Gaudet Mater Ecclesia”). That others, in love, offer respect doesn’t mean that love need not strive to earn it.

John Boyne’s novel closes with Father Yates begging his nephew’s forgiveness. The boy was sexually abused by a priest, a friend whom his uncle had brought into the home. Father Yates didn’t know, but he must fearfully ask himself if he should have.

Perhaps there is hope. Fatherhood is a gift from God, but those honored with the name of Father must model themselves after the Good Shepherd, the one who laid down his life for his sheep. Paternity can’t presume upon itself. No, to the contrary, it must selflessly expend itself, protecting and loving.

Job 38: 1, 8-11 2 Corinthians 5: 14-17 Mark 4: 35-41