On Monday the California State Senate’s Appropriations Committee sent The End of Life Option Act (SB 128) on for assessment of its possible fiscal impact.

Co-authored by State Assembly woman Susan Talamantes Eggman, State Senator Lois Wolk and Senate Majority Leader Bill Monning, SB 128 would allow Californians with a terminal illness and six months or less to live (as confirmed by two physicians) to request a prescription for medication that would allow them to die. Similar bills have been proposed in California on six previous occasions, but the groundswell of support this time around is quite strong. Santa Barbara, Santa Cruz and Alameda Counties and most recently the Los Angeles City Council all have already called for the bill’s passage, as has U.S. Senator Dianne Feinstein.

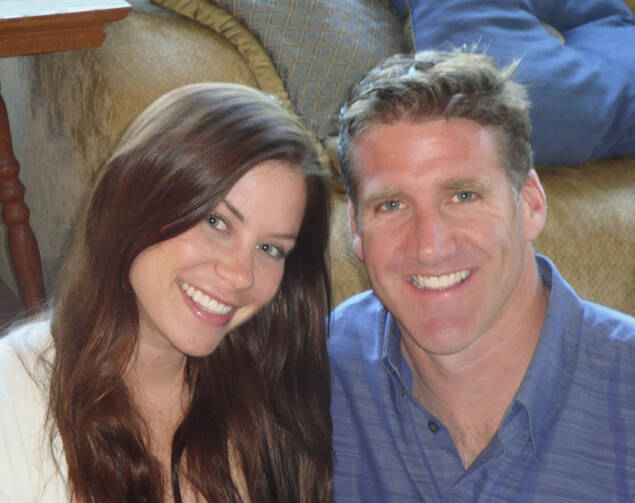

Last autumn, terminally ill California native Brittany Maynard, 29, brought new attention around the world to the question of physician-assisted suicide or death, with her YouTube videos and news interviews about her desire to be able to legally end her life in the face of a painful, inoperable brain tumor. “The way that my brain cancer would take me is terrible,” she said on one occasion. “I am not suicidal.... I do not want to die. But I am dying. And I want to die on my own terms.”

Since Maynard’s death 23 states plus the District of Columbia have proposed similar legislation. Various forms of physician-assisted death have already been made law in Oregon and Washington (by ballot) and Vermont (by legislation). Montana and one county in New Mexico also permit physician assistance in the ending of one’s life as a result of court decisions. (You can read America's recent editorial on the subject here.)

For Ned Dolejsi, Executive Director of the California Catholic Conference, a major concern is the way such legislation will end up affecting the most vulnerable in California communities. “I think it will affect health care situations over time,” he explains. “We’re in the most competitive health care market in the world. Twelve million of the state’s thirty nine million people and rising are on MediCal right now, and we’ve got millions more on subsidized health care. And yet we don’t think there’s going to be any subtle pressures [on poor people when they’re terminally ill]”?

Even for those who say they want such legislation for themselves, Dolejsi insists further consideration is required. “People should stop and think. We try to live in this delusion that this is about some objective, autonomous decision that will be made free from the pressure that occurs when we’re in this dependent position of having been given a terminal illness. But that is a fantasy.”

“We think we can control this, but the trajectory on issues of justice and life in this country are not too good.”

Since first presenting the legislation in late January, co-author Senator Bill Monning has had what he describes as a “very cordial and respectful” meeting with Monterey Bishop Richard Garcia and Los Angeles Archbishop José Gomez. “We [wanted to] acknowledge that this is an issue of importance to the Catholic Church,” says Monning, “and [that] our intent was not to challenge Church doctrine.”

Monning argues that the legislation involves “a very limited universe of people” and includes many layers of protection against abuse, including requirements that two separate doctors agree that the patient has less than six months to live; a private session between the patient and a doctor to ensure that the patient is mentally competent and not feeling pressured; insistence that insurance companies cannot limit or modify their care based on the reality of this option; and the insistence that this measure cannot be exercised on a broader basis, such as age or disability.

Monning notes that the law also requires both doctors to walk the patient through all other palliative care, hospice care and pain management options. “We don’t see this as the only option,” says Monning, “but as part of a range of options.”

Speaking to that range, Doctor Joseph Rotella, chief medical officer of the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, whose members include nearly 5,000 palliative and hospice care medical professionals nationwide, notes that while the AAHPM is “very much neutral on whether the practice should be legalized and whether physicians should participate”, its members find the “bigger issue [to be] that there are a great deal of people who need high quality palliative care or hospice but don’t get it.”

Rotella notes, though hospice care has been available via Medicare for decades, half of those who could use it never get it, and half of those do use it have it for three weeks or less. Likewise, many who could benefit from palliative care do not receive it.

“We look at this,” says Rotella, “and say the real high quality health crisis is to make available quality palliative care for all, rather than focus on the small number of people who get it and it’s not enough.”

Concern about pain management has long been a major topic in conversations about the benefits of assisted suicide. Intriguingly, Oregon and Washington’s surveys of those who choose to use life-ending medication consistently indicate that pain or fear of pain is not a major factor in their decision. According to Oregon’s 2014 report, since the law went into effect in 1998 91.5 percent have expressed a loss of autonomy as a major concern; 89 percent have pointed to their inability to do things they enjoy, 80 percent to their loss of dignity and 40 percent to the fear of being a burden to family, friends and caregivers. Only 25 percent have expressed concern about pain.

Retired Methodist minister Reverend D. Ignacio Castuera, who serves on the board of Compassion and Choices, a main national advocacy group for what they designate “Death with Dignity” legislation, argues that these laws serve to put the poorest members of the California community on an equal footing with the wealthiest. He recalls “seeing situations where families were very much drawn into all kinds of desperate moves in order to assist a person in their family,” while wealthier parishioners could travel to countries like Switzerland or get medical professionals to help in one way or another.

Castuera refuses to be swayed by the kinds of unintended consequences of which Dolejsi and others warn. “It hasn’t happened in Oregon in seventeen years,” he argues. “And there’s never going to be enough proof for those who think it’s going to be a risk.”

(In contrast, the stated position of the United Methodist Conference is that “We reject euthanasia and any pressure upon the dying to end their lives. God has continued love and purpose for all persons, regardless of health. We affirm laws and policies that protect the rights and dignity of the dying.”)

Similarly, Stockton Bishop Stephen Blaire says the real question is how to enable people to fully appreciate their death. “Dying is a religious moment,” he explains, “and we want to help people to die fully as a human being.” Pain is something that can and should be managed; “we believe very much in palliative care.” But at the same time, “To think we can be free of every suffering is also not possible. We don’t promote suffering, but we do try to help people find meaning and significance in it.”

“I think we have to show that as a church we see the meaning of death—that it has significance, that for us it’s a transition, an end to our human existence, but a transition to a new and eternal life.”

The California Senate must pass SB 128 by June 15 for it to move forward to the State Assembly. The Assembly would then have to pass it by September 11th for it to become state law.

(In the coming weeks I will post again on the issues surrounding assisted suicide and the challenges posed by the most recent legislation for the Catholic Church.)

Correction: May 13, 2015

A previous version of this article said the California Senate must pass SB 128 by June 11. The correct deadline in June 5.

The number of states that have proposed physician assisted suicide legislation since the death of Brittany Manyard was misidentified as 20. Twenty-three states plus the District of Columbia have proposed similar legislation.