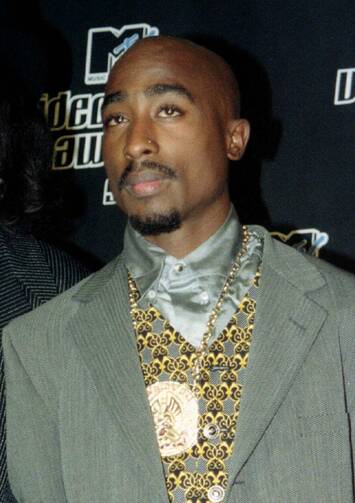

On Sept. 13, 1996, Tupac Shakur died in a hospital in Las Vegas after he was shot in a drive-by shooting six days earlier. Twenty years later, while his legacy as a rapper and entertainer is still debated in barbershops and Twitter feeds, his impact is undeniable.

Shakur was born in Harlem, N.Y., on June 16, 1971 to Afeni Shakur and Billy Garland, active members of the Black Panther Party. Growing up around activists involved in black liberation movements would play a huge role in the social awareness of his music.

Like many musicians, and all of us, he was not an uncomplicated person. Praised for the poetry and social consciousness in his art, he was also critiqued for misogynistic and violent lyrics contained in much of his music. As the two foremost hip-hop heads at America, Olga Segura and Zac Davis sat down to discuss his legacy.

ZD: When I was reading all the tributes today, one of the things that shocked me was how young Tupac was. I always knew that, but re-learning at 23 that one of your favorite artists was murdered at 25 is a bit shocking. I think the first song that I remember digging into beyond his most famous ones was “Life Goes On,” where 2Pac is paying tribute to his friends that have fallen “victim to the street,” and ruminating on his own death. Nowadays I try to be aware of what I bring to hip-hop music as a white guy from small-town Ohio, but I can’t say I was that aware of structural injustice and privilege at 13. I hadn’t dealt with the death of a friend, or growing up in inner-city Oakland, but—and this can be an unpopular opinion today—I think art can transcend all of that. That, and I’ll always remember Tupac as my first introduction to conspiracy theories. Me and couple friends fell pretty deep into the “Tupac is still alive” internet forums. Olga, you hail from the same city as Tupac—did that influence how you came to his music?

OS: Absolutely. Growing up in the Bronx, Tupac’s music—and all of rap and hip-hop culture—was just a part of our everyday lives. He was born and raised in Harlem, so we saw him as New York as we were. Some of us related to the lyrics; others just appreciated the music for what it was lyrically, musically. So despite being hailed as a West Coast rapper, he was as much a part of our N.Y.C. coming of age as Biggie Smalls, Nas or Jay Z. Aside from his music, I grew up watching him act. The first movie of his I saw was “Poetic Justice,” a romantic film starring Janet Jackson. And my father loves “Juice,” so I watched it often. Released in 1992, it stars Tupac, Omar Epps, Jermaine Hopkins and Khalil Kain as four young men growing up in Harlem. He was a fantastic actor.

ZD: So something that’s often brought up in discussions about Tupac, and all rap and hip-hop, is the misogyny and violence found in his lyrics. I have a lot of thoughts on this, but do you want to start?

OS: Sure. I’ll start by quoting director Ava DuVernay: “To be a woman who loves hip hop at times is to be in love with your abuser. Because the music was and is that. And yet the culture is ours.” It’s a provocative statement that captures the tension female hip-hop heads feel. A part of me is often troubled because there are artists and lyrics that go against the very beliefs I hold as a feminist. However, hip-hop started in the South Bronx. It started in the ghetto, created by people of color. It’s a movement that captured our voices, our culture at a time when we had no other outlets. And like every movement in history, it’s not perfect. No art form is. Yes, Tupac had misogynistic lyrics, but so did artists like Guns N’ Roses, The Police and The Rolling Stones.

ZD: Yeah I’m always a bit torn about these types of criticisms. On the one hand, yes, there’s a lot in Tupac’s music, and in all hip-hop, that dehumanizes women. And the police. Yet I think a lot of times this type of question is shaded by a thinly veiled racism. We like to pretend that these same type of complications aren’t in other genres as well, or that the music gods of past weren’t without their own moral complications. In his defense, I’ll just let 2Pac speak for himself

If I upset you don't stress, never forget

That God isn't finished with me yet

After all, holiness and virtue are unfinished projects for all of us—though we don’t typically react well when our public figures turn out to be multi-faceted human beings.

OS: Great point. I think whenever you see critics jumping to denounce rappers and their work, there is, more often than not, an element of racism. Because it is a genre created by artists of color, about the experiences of African-Americans, Latinos, etc., rap can become a target of criticism because it doesn’t speak to the “white standard” Hollywood and the music business too often purvey. Also, that line you quoted brings up something else we wanted to get into—where do you see religious themes in Tupac’s music?

ZD: I think one of the critiques of Tupac that irks me most is that his music is nihilistic. Sometimes when he’s rapping about suffering and life in the ghetto, it ventures into despair. But some of the most beautiful prayers start there. It’s like what Henri Nouwen says, how our life is “a time in which sadness and joy kiss each other at every moment.” Look at “Thugz Mansion.” It’s so eschatological. Life is full of suffering, but we’re made for the Kingdom, where “thugz get in free and you gotta be a G.” I also think there’s a natural connection to the social justice concerns of Catholic Social Teaching and Black liberation theology.

OS: Oh, absolutely. First, Tupac’s parents were active Black Panther members; he grew up immersed in the concept of black liberation. Second, he was an African-American man living in the United States in the 1990s. He understood black suffering. He captured the oppression and inequality black Americans were facing, and are still facing today. Look at his words in songs like “Unconditional Love,” where he raps, “All my peers doing years beyond drug dealing / How many caskets can we witness / Before we see it’s hard to live.” Or “Keep Ya head up,” “They got money for wars, but can’t feed the poor / Say there ain’t no hope for the youth…/ And then they wonder why we crazy.” Or “Changes,” “Cops give a damn about a negro? Pull the trigger, kill a n***a, he’s a hero. / Give the crack to the kids who the hell cares? One less hungry mouth on the welfare.” Like you mentioned, Tupac wasn’t nihilistic; he was fully aware of the suffering of his people, of the world. And on that note, where can fans unfamiliar with Tupac’s music start?

ZD: If you haven’t heard it already, “Changes” is a perfect place to start. Also “Thugz Mansion,”“Brenda’s Got a Baby,”“Keep Ya Head Up,” and “Ghetto Gospel.”

OS: Those are great. I’d add “Dear Mama” and “Hail Mary.” I’d also recommend his poetry collection, The Rose That Grew From Concrete.