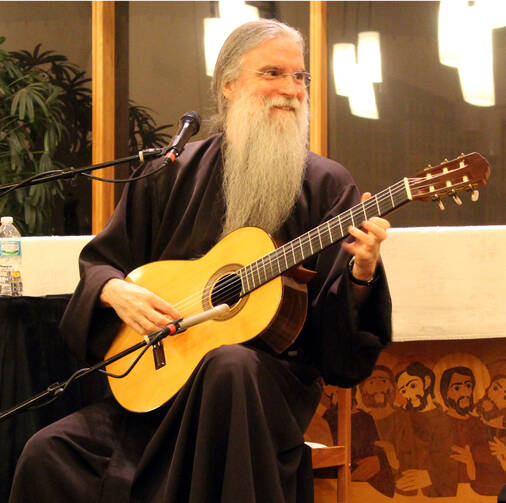

John Michael Talbot is an Arkansas-based Catholic singer-songwriter, guitarist, author, television host and founder of a monastic religious community. A major figure in contemporary Christian music, he has recorded more than 50 albums of worship songs, including hits like “Come Worship the Lord” and “Holy is His Name.” In 2011, he published the Mass of Rebirth, a Contemporary Chant setting of the new translation of the Roman Missal that “honors Pope John Paul II’s call to breathe from ‘the Eastern and Western lungs of the body of Christ’” by blending Eastern and Latin Rite musical textures.

After dropping out of school at 15 to be a guitarist in the country-folk-rock band Mason Proffit, Talbot dabbled in Native American religions and Buddhism before joining the Jesus Movement, eventually discovering St. Francis of Assisi and converting to Catholicism in 1978. Moving to Berryville, Ark., he established the Little Portion Hermitage on land purchased during his Mason Profitt days. In 1980, he founded the Brothers and Sisters of Charity there as a Public Association of the Faithful, under the formal approval of his local bishop. As minister general of this "integrated monastic community" with celibate brothers and sisters, singles and families, Talbot continues today to host musical retreats at the hermitage while traveling around U.S. Catholic parishes on ministry tours. In 1989, he obtained permission from the church to marry Viola Pratka, a former Incarnate Word Sister who had come to the community in 1986.

Talbot’s television show, “All Things Are Possible,” is produced by the Trinity Broadcasting Network for its cable affiliate The Church Channel. Salt and Light Catholic Media recently picked up the show and will begin airing it this fall throughout Canada. On July 15, I conducted the following interview with Talbot, who was on a ministry tour in Bentonville, Ark. The following transcript of that interview has been edited for content and length.

A lot of things have changed since the 1970s. Has the music changed for you?

Not for me, but I’m not doing as much because the music business for older artists has gone belly-up. You know, the digital revolution, economic issues and related royalties—I have to have 10,000 streams of “Holy is His Name” to make one dollar, and out of that one dollar I have to pay all the expenses of producing that song. For the young kids who don’t know any different, they just navigate it, and they don’t realize they’re selling 10 times less than what artists once did. So they don’t have any problem with it, but for older artists it’s a bit disorienting. Essentially the landscape has totally changed, so I’m not ruling out music, but I feel like a quarterback without anybody downfield to catch for me anymore. So I’m not totally inspired to make a lot of new music. But I don't rule it out. I probably will still write a few songs, and I don’t doubt that if I’m remembered for anything, I’ll probably be remembered firstly for my music.

When I play music in these ministries we do around the country, I look up after the song and people are crying, they’re weeping. Music has just an amazing capacity to reach people on a deeper level, and the music I make is very contemplative and it’s very healing. It’s not pop music, it’s not folk music, it’s not classical music, and it’s not strictly speaking liturgical music. It’s kind of just its own little sacred music in its own category. I mean, I’ve sold millions and millions of records, but there are some people who don’t like it—even though they’re few and far between.

How has your faith changed or evolved since you converted to Catholicism 35 years ago?

Well, it’s certainly grown deeper. My love for patristics and for the monastic tradition is intense and continues to grow. I’ve felt more comfortable in branching out into interfaith things because I come from that very solid base of Christ, the apostles and the whole apostolic succession and patristics and all that. I just feel very solid in my base, so I’m able to reach up higher. My spiritual father used to tell me that everything that came before Christ funnels into him, but everything funnels out from Christ as well, and you end up going back into some of those same areas. I can engage in all kinds of dialogues without losing my base and getting lost in syncretism. That’s an area that’s been delightful.

But the other thing is that the older I get, I find that my message now revolves around the fact that only 17 percent of Catholics in America are going to church, and only 15 percent of Catholic young people are going to church. If it were a denomination, the second-largest denomination in America would be non-practicing Catholics because there are 30 million of them. I think the great Hispanic hope is a false hope because most of the Hispanics who come up north are leaving the church. And what are they looking for? They don’t want to get away from the teaching of the church, they don’t want to get away from the sacraments—I think they miss those things. But they get away because they’re looking for engagement and they go to Masses up here in the developed north where they see a bunch of mummies in a museum walking around like zombies, and music that is uninspiring, and preaching that is boring. And they leave. So the challenge before us is simple, and really Pope Francis has shown us the way. You know, he says “I call everyone at this very moment to a renewed personal encounter with Jesus Christ.” That’s how he begins “The Joy of the Gospel.”

Does your recent shift to television affect the way you do ministry in this context?

It does and it doesn’t. I really shifted gears in 2008. We had a monastery fire, the music industry got turned on its ear, and I saw that the other artists my age were doing a few concerts throughout the year here and there—kind of dying on the vine. It seemed to me that I could either do that or start going out to share what I do on my retreats with parishes. So I started doing one-to-three-night ministries, 150 events a year in parishes all across America. We started crisscrossing the United States, having a blast. And I did a DVD shoot of what I bring to parishes. The people over at Trinity Broadcasting Network saw it and Father Cedric Pisegna wanted to use some of it on his “Lived with Passion” show, which airs on The Church Channel, an evangelical-based TV ministry that is TBN’s ecumenical arm.

Then I went on their big prime time show that goes out to 400 million homes around the world and they were just really jazzed, so they invited me to do a TV show. So I’m bringing an engaged encounter with Jesus Christ, as a Catholic, on this weekly show on a non-denominational Christian channel. Right now we’re getting really good ratings. Father Mike Manning, Father Cedric Pisegna and I are the only Catholics on this network and it’s a really exciting opportunity. You know, EWTN is great, but they don’t reach nearly as many people as this other network does. We’re excited to be out there as Catholics, bringing our faith in a way that’s engaged and enthusiastic, yet also taking folks into the great depth of what the church has to offer because of who we are as Catholics. We’re bringing the contemplative tradition, the liturgical tradition, the sacramental tradition and the monastic tradition to an ecumenical audience around the world.

You know, next year we’re doing a show called “Monk Dynasty,” because I’ve got the beard, so why not? But it’s serious stuff. We’ll be going through the desert fathers, Basil, Augustine, Jerome and Cassian—and bringing that teaching to this audience in a way that’s exciting and relatable. What do these guys from the ancient past have to say to us in the midst of our walk with Christ right here in modern America and all around the world? Again, this program gets into 400 million homes around the world, and now it’s branching out: Catholic networks are picking it up, including NET in New York, the Shalom network out of India which goes to a couple hundred million folks, and Salt and Light in Canada this fall. Boston Catholic is giving it a look and I’d be surprised if they don’t want it.

How has this TV ministry affected you personally?

We’re going out to all these homes and I’m excited. I’m actually more excited now than I’ve ever been in my whole ministerial career. Here I am, over 60 years old, and I feel like I’m 24 again and we’re reaching more people than we’ve ever reached before. And we’re just having a blast. What I see out there is that Catholics are ready for a revival, to use old-fashioned language. They’re ready to get on fire for Christ again. We’ve had so much bad news for over a decade and Catholics are tired of it. They’re ready to feel good about their faith again. So all I’m doing is going out there as God’s clown to get people excited. My preaching is really upbeat, but my music takes people down deep into contemplative prayer, and there’s just all kinds of conversion and healing that happens. I couldn’t be happier.

There’s been a movement in recent years, especially under Pope Benedict XVI, to recover some of the beautiful Latin hymnody. At the same time, Life Teen has moved youth liturgies more in the direction of rock music. Is there still a place for the guitar at Mass?

I love ancient sacred music, and I love it when it is prayed well. But generally speaking, I think Catholic music stinks. I hate to say it, but it’s true of the music in the average parish. Nobody sings, the musicians are discouraged, and we really need a shot in the arm. I think there’s ample place for guitars at Mass. But I think it’s a gross misunderstanding of the genre to say that what I do is folk music. Even well trained musicians have a tendency to do that and be rather dismissive of the guitar. And I say “well good, you keep playing the music of people who lived hundreds of years ago and bore everybody to death. You’re really good at that.” You know, I’m basically the Segovia of Catholic music. Segovia’s mission was to say guitar is indeed classical, that you can play classical music on the guitar. When I listen to the music I really like, I listen to classical music, but then I listen to Paul Simon.

So does the guitar have a place? Yes, but the guitar has not yet been fully tapped as a truly legitimate instrument in real liturgical music. I would say it should to be used more like a harp, or like a lute, or like a continuo was used in the early Renaissance music. The guitar has a definite place, but you can’t just be up there strumming it. Don’t get me wrong, because there’s a time and a place for contemporary music. Music is one of the things that cause young people to leave the church in droves and go to megachurches.

What can Catholics do to change this situation?

We need to be engaged! We need engagement, not entertainment. That means full interior and external participation. Really singing, really listening and supporting the homilist, and really praying to participate fully in the Real Presence of Jesus at every Eucharist. You see, 50 percent of the people sitting in the megachurches are non-practicing Catholics. They go there because the music is engaged, it’s music they can relate to, and they go there because the preaching is darn good. You know, the pastors get up there and they hold their audience for 30 or 40 minutes every Sunday and people don’t want them to stop—they’re that good.

That’s what we need. Not entertainment, because I’m against the idea of using entertainment in worship, but I’m a strong believer that we need engagement. We need music that reaches people where they are. And I’ve got news for you, a few people do it. Mike Zabrocki at Holy Trinity in New York really knows his stuff when it comes to music, engaging the congregation and choir. He not only knows his contemporary music, because he’s an old rock-and-roller, but he knows his liturgical music really well. So it can be done. I tell old folks, and there are a lot of them my age sitting out there: Look, I know it’s uncomfortable, but you’ve got to step out of the boat and walk on water. That’s scary, no doubt, but you’ve got to sing at Mass if you care about the youth. Because if young people don’t see you singing, praising God and being engaged, they’re going to walk out sooner or later. Now I’m a big believer they’ll come back because they miss the sacraments, but they’re going to walk out because the singing is not engaging and people are looking at their watches while the deacon or priest is preaching.

How can improving our preaching and music have a deeper impact on people?

Once we’ve got better preaching and we’ve got better music, we’re going to lead people into a truly engaged encounter with Jesus Christ at every Eucharist. At every Mass, Jesus comes from heaven sacramentally for each one of us. It is personal, it is intimate, it is life-changing, it is powerful. We cannot just go through the motions and receive Jesus in a robot-like way, week after week and year after year. It can change, we can turn things around. All things are possible with God. But we’re at a decision point in America where we can either repent and prosper or not repent and perish. Right now we’re on a course that’s dead set for Western Europe, where you’ve got big empty churches that are beautiful museums to the past. People are ready to change and do something, but we’ve got to step out of the boat. That’s what I’m preaching out in the parishes, and when most people hear it, they say “dadgummit he’s right.” And they’re ready to change and do something, to step out of the boat. That’s scary because we’ve been doing it the same way for decades and we don’t want to admit that it isn’t working.

Why does the acoustic guitar, even poorly used, speak deeply to so many people at Mass?

It has the appearance of being contemporary and it’s safe, it’s not real loud. But it also runs the risk of being stuck in a folk music past that is really neither fully contemporary, nor classical and traditional. What I like about the classical guitar I play is that it’s mobile. It’s a great instrument for itinerant ministry because it can go anywhere. I’ve taken it to the fields of Central America, and to the Philippines, and to the Holy Land, and I can take it into basilicas and cathedrals. It’s at home in either kind of place. But you can’t take a pipe organ out into the field with a bunch of campesinos or even into their pueblo churches. So the guitar is a great mobile instrument for itinerant ministry. You know, I can put it on my back and I’m gone. If I get on an airplane, I can check it and I’m gone. It’s that easy. That’s why I like it.

What are some challenges for Catholic liturgical music today?

I’m an opponent of the sloppy, out-of-tune Mass—of what I call the “eh-wimoweh” syndrome. You know, you remember that song The Lion Sleeps Tonight? If you do your history of contemporary liturgical music in the United States, you’ll find that Catholics were doing the folk Mass before Protestants brought it into their service music. Ironically, it was the Southern Baptists who went to guys like Joe Wise and Ray Repp and Sebastian Temple to find out how to do it. How do you bring contemporary music, which was folk music in those days before the Beatles, into church? How do you bring folk music into worship? And they had great dialogues. But then we Catholics stayed stuck in the 1960s while the evangelicals just took off. They started incorporating contemporary music with each successive generation and they did it very effectively. Now the mistake they made, because they don’t have the checks and balances of the Catholic hierarchy, is that they often moved too quick, by which I mean that their worship just became entertainment.

Our problem as Catholics is the opposite. We sometimes move too slowly and we get stuck in the past. So we conserve the past, but we sometimes get trapped there. Folk music is a carryover from the ’60s, really, and maybe it's time for us to admit that some of the contemporary folk music from those singers—you know, I call them chicks with guitars, who kind of yodel as they sing—is really just a liturgical anomaly from that era. Some of it is good, but some of it is just stuck, and it’s not really contemporary anymore, and it’s not really traditional either. So what is it? Don’t get me wrong, I think the St. Louis Jesuits wrote some really good songs. In their whole repertoire, there’s probably 10 or so really great tunes that are going to be sung for a long time in the church. But that's not enough.

Can the guitar be an instrument of God’s voice just as much as an organ or piano?

If the player is good, yes, absolutely. There’s an art to playing sacred music on a classical guitar, and doing it in a way that is both classical and contemporary all at once, and it takes a rare musician to be able to do it right. There’s an old saying that the tone is in your fingers, it’s not in the guitar, because it comes from your life and it comes from your heart. It comes from years and years and years—and thousands of hours—of practice. Then you go out and do a simple song, but behind every note is the ability to play hundreds of notes. So the guitar is the people’s instrument, it’s “folk music” in that sense, and in that sense almost anyone can play it. Guitarists do need to have some lessons. But on another level, I don’t think the guitar has reached the level that it could reach in its use in worship—I think that’s still a bit ahead of us. It takes a great player to put it all together, somebody who has musical training and experience, but also the spiritual training and experience as a sacred musician.

Many people know your songs and your voice, but they may not know you are the married founder of a monastic religious community. How do you explain the Brothers and Sisters of Charity to them?

Basically, we’re bringing ancient integrations into a modern setting. John Chrysostom said that anyone who is serious about the Gospel is a monk without even knowing it—because the word “monk” just comes from the Greek for “one and alone,” to serve God and God alone. Historically, many of the early monastic founders like St. Ammon of the Desert were married. They lived a continent life, but they were married, and Ammon never renounced his marriage vows. And yet he was the founder of several historic monastic foundations. The Celts had monks on the first circle, nuns on the second circle, and families on the third circle, and it was a big monastic village. Often when hermits went into the desert, soon monasteries would grow and villages would grow around the monasteries. So it’s in our history and we are doing the same thing.

Are there any challenges to being the married founder of a monastic religious community that includes celibate members?

We’re not into synthesis, putting ourselves into some kind of soup without any differences between the states of life. We don’t stand for synthesis, but for integration. It’s like a Franciscan cord with strands that group together to form something strong, but you can still find each individual strand in place with its own integrity. The celibate call has its own integrity with unique needs, rights and responsibilities. It’s the same for the single state that is open to marriage, and for the family state with its conjugal chastity.

Our vows are lived differently for each state of life. As a community, we try to protect that, and we’ve done a pretty good job, but it’s a bit of a balancing act because—oh, I don’t know, sometimes families subliminally want to be celibates and sometimes celibates subliminally want to be moms and dads. That doesn’t work. So it’s important that we practice integration and not synthesis. Celibate brothers, sisters and families all have their own distinct areas of our 650-acre complex. But we come together for prayer several times a day and for one common meal, and people work together in the different works of the monastery in the different areas. So we’re doing something old in a modern setting, and communities of this kind are working in other parts of the world like Europe, where they’ve become popular and are spreading. It’s an anomaly in the United States, where the question is whether this kind of community even works here. I think we’re so independently minded that we don’t understand healthy co-dependence very well. Some people rightly question whether an intensive form of religious life, in the classical sense, is even possible here.

There’s obviously going to be a lot of misunderstanding. What do you say to people who think the Brothers and Sisters of Charity are the Catholic version of a hippie commune?

I don’t fault them too much, but it must be admitted that they are rather ignorant. You know, it’s just ignorance. It’s not intentional ignorance, it’s not malicious ignorance—it’s just ignorance. Most practicing Catholics out there in the pews love their faith, but they don’t have the time or the energy to be able to really understand the depths of Catholicism. It doesn’t mean they’re not Catholic or faithful. They are. But they don’t have the time, or the energy, or the space to really investigate the things we often take for granted as Catholics. And consequently, sometimes we misunderstand the things that we practice, so we misunderstand what religious life is, where it came from, how it’s developed. But if you know that, then you look at an experiment like ours and say “oh, I get that, it makes sense.”

What’s your current role as founder and leader of the community?

The older I get, the more I delegate authority. I have very little to do with the daily running of the community anymore. I’m the general minister and spiritual father, but I’m kind of like the founder and senior member of a law firm. You know, I still take cases and I still show up, and I am very involved behind the scenes with other leaders. But publically I am the grandpa. I get to have fun with the kids, but do little discipline myself anymore. Basically, my role is really to go around, slap everybody on the back, smile and say “attaboy.”

How many members are in the community?

I think right now we have 300 domestic members—these are people who live in their own homes, all around the country—and then we have about 35 in our monastery. We also have cluster communities, including Chicago, where they all live in the same neighborhood and go to the same parish. That’s Holy Trinity parish in Westmont, Ill. They're all highly effective secular folks. Honestly, I love the monastic expression of community, but I think we’re way ahead of our time for where America is now. I think it’s going to take years for people to understand it and actually get on board with it.

My biggest excitement right now is our domestic members, because you can’t renew religious life until you renew families, and the family in America is in an absolute tailspin. You renew families in the parishes. Our domestic members are out in parishes as pockets of God’s power, preaching the importance of family and supporting their communities. Once we see a renewal of parishes, religious life is going to blossom as well. I actually changed my position on this. I used to be more Celtic, thinking renewal could come out of religious communities and go into the society in general. I don’t think that’s going to work in the United States right now. I think we’ve got to renew parishes.

How will renewing parishes affect vocations?

Historically, we know religious life prospers in cultures where the Christian family becomes more stable, and where young people are being raised in the faith to really consider religious life or clerical life more seriously—because they have the tools that were put in place during their whole upbringing. A lot of times, when people consider these vocations now, we often bring the baggage of a broken and breaking culture that has shifted from a Judeo-Christian base to a secular humanist base. If it’s not happening, it’s already happened. So the young people considering vocations right now are great people of faith, the St. Augustines of our time, but they really have to go fight a massive tide of secular cultural values. So to become community members in the Jesuits, Franciscans or Brothers and Sisters of Charity will require young people to swim against that tide, and it’s hard to do it. It’s not easy, it takes a lot of faith, and we’re not going to have the big numbers we’ve had in the past.

How do you pray? Do you have any favorite prayers or methods?

I’m a big believer in daily charismatic praise and worship, lectio divina, and what I call “breath prayer” or contemplative prayer. The charism of our community tries to integrate the charismatic and the contemplative, the spontaneous and the liturgical. In addition to praying the Liturgy of the Hours every day when I’m on the road, and in addition to attending Mass daily at the hermitage, I try to enter into the upward “letting-go-of-self” beauty of praise and worship. The gesture of raising your hands, where you’re letting go of your old self, is an upward enthusiastic motion in God. The contemplative motion is letting the old self fall off like an old set of clothes which doesn’t fit well, and the breathing in of Jesus and the breathing out of that old self is just letting go. So it’s a very restful and contemplative experience of letting go of the old self and I’ve found in my own spiritual life that I need both motions. I need that enthusiastic motion, to get excited, and I need that contemplative motion of entering solitude and silence for long periods of time every day. So I do both and, of course, lectio divina is a very important part of that. I love Scripture and I like finding out what the words really mean.

Who are some of the people who inspire you in your Catholic faith today?

I have to be honest, when I met John Paul II and Mother Teresa, my heart soared. I felt like both these people could look into my heart in a moment. But Pope Francis is exactly the guy we need at exactly this moment in the history of the church. Benedict XVI was a reformer, he had to reestablish foundations that were eroding, I think he did a great job, but it wasn’t highly inspirational to anybody but professionals. This pope is a people’s pope and that’s what we need. He teaches us how to navigate a secular humanist environment without railing out against the evils of secular humanism and the world. Instead of focusing on what we’re not, he focuses on what we are, and I think that’s what we need. That’s what the world needs to hear. He knows you can only tell people they’re wrong for so long until they just shut you out, and he knows how to really inspire people. That’s why I tell people to read his own speeches, not the secular press accounts of them, if they really want to know what Pope Francis is thinking. He’s just knocking my socks off.

Beyond that, I have a book coming out on the Fathers of the Church called An Ancient Path with Mike Aquilina, due from Image Doubleday next January. I read the Fathers regularly. Instead of being archaic voices from the past, they were people who had to apply an ancient faith to their own contemporary setting in each successive generation, and they were amazing. Guys like Augustine, Chrysostom, Basil and Benedict applied a faith that was already centuries old to their present needs with creative fidelity. They were faithful to what had come before, but they were creative about who they were in the present, and they all hit it out of the park. So I love the Fathers and the monastics like Bruno and Francis of Assisi who make my heart soar every time. They were all just brilliant and they inspire me deeply. I believe in apostolic succession and I also believe in the succession of saints. They all take the ancient and bring it down to the present.

Sean Salai, S.J., is a summer editorial intern at America.