One of the most remarkable aspects of Daniel Berrigan’s last appearance among us—his funeral Mass at the beautiful Church of St. Francis Xavier in New York City—was the sensed experience of community among everyone, from the 25 priests and one bishop (Thomas Gumbleton) concelebrating to those crammed into the pews and aisles all the way to the back door and the steps out. Friends I had not seen in many years suddenly appeared, and others had written me condolence letters, as if a member of my family had died; they were right. What united us was our shared vision of a world in an orgy of violence, a world that brave men and women in the 1960s and 1970s felt was losing its soul and were determined to save.

Jim Dwyer wrote on the front page of The New York Times on the day of the funeral about how Dan in later years, saving only a small back pack, had discarded nearly all of is personal possessions, so nothing would distract him from his vocation of nonviolence. Jim O’Grady, Dan’s first major biographer, reported the funeral for WNYC and wrote in The Nation, “Father Daniel Berrigan was a lion of America protest, one of the most stubborn and eloquent radicals this country has ever produced.”

Dan taught my fellow 1955 Fordham graduate Dick Cieciuch at St. Peter’s Prep in Jersey City. Dan, he said, was always a gentleman, a quiet presence in the class as he taught Gerard Manley Hopkins’s poetry and led them all over to New York University for a live production of Shakespeare’s “Julius Caesar.” Years later they stayed friends, and Dan visited Dick and his wife Bernadette, who is a wonderful pianist, at their Long Island home. One day right after Dan had been released from prison, they gathered around the piano to sing, and when they pulled back the drapes from the window overlooking the yard, Dan flinched. Somehow the prison term had left him high strung, wary of a surprise.

Hyphenated Priests

Dan followed regency at St. Peter’s with four years of theology at Weston College, a few miles outside Boston. When I interviewed Dan for my biography of Robert Drinan, S.J., he reported that he found the intellectual atmosphere terribly stifling. To him the teaching represented the last gasps of 19th-century philosophy and theology, taught by men from their own notes, men who had been trained in Rome and were simply passing along what they had learned. One of the professors spent most of his time attacking the great theologians of the day—de Lubac, Congar, Danielou and Rahner—whom he dismissed as adversaries. “We were a ship of fools,” Dan wrote. “We were reassured by our captain. All, we were told, with a trimmed sail here and a good wind there, was well. And we were bound, straight as an Iroquois arrow, toward disaster.”

To ward off disaster Dan and a group of theologians formed their own study club and read articles from Commonweal and Cross Currents as they met weekly in a little cabin and asked questions they could never face in class.

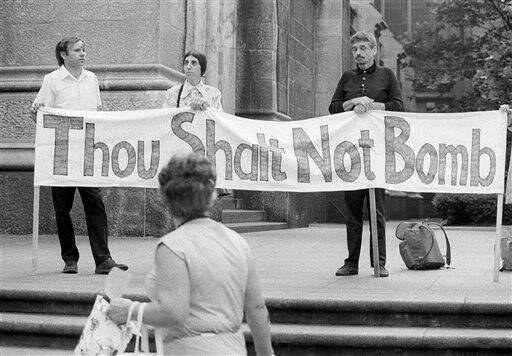

For both Dan and his fellow student Bob Drinan, S.J., the great moral issue of their time was the Vietnam War. Both were engaged in what became, for a while, a major church controversy about the “hyphenated priest.” In France, to reconnect the church with the common people, many priests formed the worker-priest movement and took jobs in factories rather than stay home in a parish rectory. Should the hands that held the consecrated host at Mass also swing a hammer pounding steel? Drinan answered the question by running for Congress in 1970, where he stayed until 1980, long enough to impeach President Nixon for his illegal invasion of Cambodia. Dan, along with his brother Philip, raided the draft board in Catonsville, Md., and burned 380 files in the parking lot with homemade napalm.

An ‘America’ Editor

They were not alone. David S. Toolan, S.J., who was ordained with me in 1967, went on to teach philosophy at Canisius College in Buffalo. Later he lived with Dan in the 98th Street Jesuit community, one of the best Jesuit communities I have known. Several were active in civil disobedience, but they prayed together and openly shared their feelings, fondness and fears in dialogues on retreats.

In a stunt that made some headlines, Dave, with a few associates, made an appointment for a meeting with a high-ranking Pentagon administrator, the director of Selective Service, Curtis Tarr. But they had more than a mere meeting in mind. They were ushered into the director’s office, and as Dave reached out to shake the director’s hand he pulled out a pair of handcuffs, snapped them on Tarr’s wrists and declared the director under arrest for the crime of sending all these young service men to die.

Dave, my friend, went on to replace me as book editor at Commonweal and eventually moved to America, where he wrote books, worked against poverty in developing nations and ran the Catholic Book Club. He traveled to pre-Castro Cuba, Latin America and to Russia, in spite of the pain from the cancer that would take him in 2002.

On Nov. 16, 1989, at the campus of the University of Central America, a contingent of soldiers burst into the residence of the Jesuit faculty and massacred six scholars and two lay associates. A few days later, at Loyola University New Orleans, a student friend asked me for advice. The visiting professor, Dan Berrigan, was also teaching them civil disobedience and had invited his class to take over the New Orleans federal post office, the local symbol of the United States government, which was supporting the army of El Salvador. Should he take part? We talked and I left it up to him. He joined the demonstrators. The Jesuit rector, Gerald Fagin, S.J., and I showed up to support them. A policeman asked Gerry to use his authority and send the students home. No, said Gerry, he was on their side. They were arrested and tried. I attended the trial. I’ll see that student in a few weeks and will ask him, after all these years, what he learned.

A former Jesuit and friend, Gerry Drummond, wrote a beautiful letter to a long list of friends describing Dan’s wake and funeral, including Dan’s appearance in the coffin. “Except for a full face, he was just skin and bones. You could touch him. I touched his boots and his shoulder. Others kept touching the top of his head. And all going by were probably wondering if they had touched a saint.”