Bosch and Bruegel: From the Monstrous To the Ordinary

Before 1500, no Western European paintings focused on ordinary people and their lives, writes Joseph Leo Koerner, a prize-winning art historian and the Victor S. Thomas Professor of the History of Art and Architecture at Harvard University.

Genre painting, as such paintings are known today, lay in the future. Instead, painters treated religious and historical subjects. Any ordinary people in paintings stood anonymously in the background or as bit players in dramas about the gods, biblical characters and saints, military heroes and royalty. In Northern Europe, however, that practice changed during the 16th century. How and why is the subject of Bosch & Bruegel, Koerner’s fascinating and lavishly illustrated tome.

The author observes, compares and, most important, contrasts the works of two Netherlander artists, Hieronymus Bosch (1450-1516) and Pieter Bruegel the Elder (1525-69). Koerner’s thesis is that Bruegel, who at first imitated Bosch, diverged and ultimately surpassed him as he developed a new focus for painting.

The author observes, compares and, most important, contrasts the works of two Netherlander artists, Hieronymus Bosch (1450-1516) and Pieter Bruegel the Elder (1525-69).

Decades of scholarship and personal experience inform this book, based on the A. W. Mellon Lectures that Koerner delivered in 2008 at the National Gallery of Art in Washington. Over and over, the author shows readers how to look at art, a demonstration that alone is worth the price of the book.

Still, this book takes effort. While historians and theologians can readily dive into the discussion, general readers may find it demanding. All effort expended will be richly rewarded. Readers may wish, as Koerner suggests, to begin with the thesis in Chapter 4 of the Introduction, “From Bosch to Bruegel.” I enjoyed returning to the opening chapters later, as a finale. Part I, “Hieronymus Bosch,” is the longest, most complex and controversial section of the book. Part II, “Pieter Bruegel the Elder,” compellingly makes the author’s case with one beautiful painting after another. I found it worthwhile to look up many of the paintings online in order to zoom in on the telling details.

BOSCH’S ENEMY

To understand Bosch, the concept of “enemy painting” is key. It refers to the cosmic warfare that underlies Bosch’s religious works. Since God and Satan (God’s enemy) battle across time and place, the enemy is pervasive, beginning in Eden. Bosch adds exotic animals, plants and other menacing characters to biblical scenes to show “enemy presence.” Note the perversity of nature in the grotesque figures of “The Temptation of St. Anthony” and the contorted faces of onlookers in “Christ Carrying the Cross.” Surprisingly, the enemy infiltrates “Adoration of the Magi.”Bosch leads you right to it. Behind the exotic bird atop the African king’s gift lurk several enigmatic figures, including an exposed man draped in red, with a possibly leprous sore on his ankle. Atypical in most Epiphany scenes, Bosch’s enemy contaminates the universe.

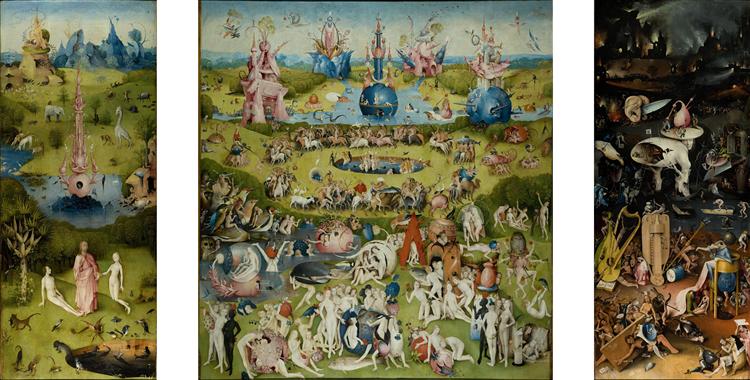

Bosch’s most elusive painting, originally untitled but in this book called “The Garden of Delights,” has perplexed centuries of viewers. Koerner examines it in “The Unspeakable Subject.” Contemporary scholars think the work was commissioned by one of the counts of Nassau, either Henry or Engelbert II, rather than by any church. According to a diary account by an eyewitness, the painting was kept at their palace in a hidden chamber and shown privately for the owner’s amusement. Today, the painting is one of the most popular works on view at the Prado.

Bosch gave “The Garden of Delights”a typical triptych form, but in place of a biblical scene in the center, he depicts explicit sexual and violent content, frolics in a sexual theme park, though no one there looks happy. The picture may have been a risky undertaking, since where and when Bosch worked, masturbation, adultery and same-sex intercourse were offenses punishable by death. Perhaps the altarpiece design, which could be kept closed, was crafted to disguise a secular painting. Or perhaps Bosch’s battle between God and Satan is the subject, the wages of rampant sinfulness, making this a religious work. If so, Koerner raises a sticky point about Bosch’s role as an artist. Does Bosch, in directing viewers right to his most lurid scenes, cause them (us) to sin by visually taking part as voyeurs in humanity’s unbridled flesh-fest? Whatever one thinks of Koerner’s point or of Bosch’s image, this particular painting clarifies the distance between Bosch’s worldview and Bruegel’s.

BRUEGEL’S PEASANTS

Pieter Bruegel was born nine years after Bosch died. As a young designer of engravings, Bruegel imitated the wildly popular Bosch. But any traces the “enemy” disappear in Bruegel’s work. No enemy is present in “Alpine Landscape with a River Descending from the Mountains,” one of the majestic landscape drawings Bruegel made while crossing the Alps. Rather than fantasy, Bruegel paints local scenes, conveying his own time, place and culture, even situating biblical stories in the Netherlands. In his “Christ Carrying the Cross,” a windmill turns atop a distant rock.

Particularly during his last years, Bruegel paints ordinary people going about their business, revealing his view of human nature. Not only is Bruegel’s affection for peasants palpable, but he makes some of them life-sized, signaling their importance (“The Peasant Dance”). That was new. Fully human, Bruegel’s peasants are far from perfect, yet none are beset by demons. When Bruegel’s peasants mock their disabled neighbors or make sport of the anorexic or obese (“Battle Between Carnival and Lent”) or display indifference toward the infant Christ in their midst (“The Adoration of the Kings in the Snow”), they are not manipulated from without but motivated from within. The point reflects a changing mindset relevant today. Readers will recognize in Bruegel a view of humanity and of the self that reflects their own.

Readers will recognize in Bruegel a view of humanity and of the self that reflects their own.

Many factors influenced Bruegel’s singular shift. First, the Christian story of fallen humanity, depicted by Bosch, found competition from the rise of secular humanism, as reflected in Bruegel. Second, Christians were embroiled in an internecine war that made painting religious subjects dangerous. The Protestant Reformation raged on after Martin Luther’s death in 1546, the year Bruegel turned 21. Two decades later, Calvinist iconoclasts in the Netherlands stripped churches of their art. In 1567 the third Duke of Alba brought an army from Spain, which controlled the Netherlands, to crush heresy. Trials were held in the town where Bruegel lived. An artist friend of his was interrogated. When the duke had finished, thousands of townspeople lay dead. Bruegel instructed his wife to destroy some of his paintings, lest she be held responsible after his death. One wonders how “Christ Carrying the Cross”survived: The troops wear the red coats of imperial mercenaries. Third, advancements in printmaking technology and global markets allowed artists to make multiple copies of a work at affordable prices. Artists no longer had to depend on commissions.

In sum, Koerner lays out the ironic path from Bosch to Bruegel, the art of ordinary life arising from the art of the phantasmagoric and monstrous. “Today Bosch is seen,” writes Koerner, “as the last great Medieval artist depicting an absolutist Christian worldview. Bruegel, by contrast, is seen as the first artist to put his skepticism into pigment, ushering in a more modern worldview.”

In his audacious focus on ordinary life, Bruegel stepped out of Europe’s medieval past and into modernity. And this book, by shining a laser on the 50 years during which Bruegel developed genre painting, lets readers peek into the Renaissance origins of their own thought world. Seldom has art history seemed so relevant.

This article also appeared in print, under the headline “From the Monstrous To the Ordinary,” in the Spring Literary Review 2017, issue.