100 years after World War I, is it possible to hope in human progress?

G. J. Meyer is mad as heck at the winner of the 2016 presidential election, and he’s not going to take it anymore.

A common enough sentiment, that, but Meyer’s target in his far-reaching study The World Remade: America in World War I is not the current president but rather the victor in 1916, Thomas Woodrow Wilson. Wilson’s administration, of course, marked a critical turning point. Whereas America’s path toward empire began decades earlier, it was under Wilson that the United States became an authentic world power. The country’s spectacular wartime mobilization raised production to unimagined heights, and the United States, habitually a debtor nation, emerged from the war as a net creditor and the only major economy left standing after the European catastrophe. Having also become, virtually overnight, a first-class military power, America stood ready to impress its geopolitical vision upon the world. Yet Meyer’s panoramic assessment of America in this period, and particularly its commander in chief, is staunchly negative, and he argues his position passionately.

Once a revered icon of American progressivism, Wilson has lately taken fire from both political flanks. Conservatives malign him both for his internationalist foreign policy agenda and for spurring a massive expansion in federal power. The liberal side of the discussion, where Meyers aligns himself, has justifiably denounced Wilson’s policies regarding race (he segregated the Civil Service) and First Amendment freedoms (his efforts to crush and criminalize dissent during the war are a stain on our history). Truly, there is much to criticize in the legacy of our only Ph.D. -holding president.

Yet Meyer ventures beyond the obligatory Wilson bashing. The president is, for him, an emotionally brittle man—one who, despite being “brilliantly gifted, impeccably upright and guided by high ideals,” was morbidly insecure and nursed “a bottomless hunger…for unqualified praise.” In Meyer’s account, as in classic tragedy, his subject’s personal flaws contain the germs of a larger disaster; Wilson’s weaknesses led inexorably to twin debacles: the catastrophe of the Versailles Treaty and Wilson’s own physical collapse immediately after a nationwide tour in which he struggled, in vain, to win public support for his proposed League of Nations.

Despite admirable research and a remarkably forceful presentation, however, Meyer’s vilification of Wilson won’t quite wash. First, tragedy requires the author to evince some sympathy for the fallen hero. Meyer, who calls Wilson “a past master” of contempt, rivals his subject in this regard. His tone is too often cruelly sarcastic. Surely the defeated Wilson, felled by a massive stroke, only intermittently coherent and delusionally dreaming of a third term, is as fit a subject for pity as any figure in our history. Meyer shows none. Meyer, perhaps more than his subject, has a penchant for meanness, and it lessens his work.

Meyer’s analysis, particularly of Wilson’s shortcomings at Versailles, ironically commits the same error that undermined Wilson himself: the belief that a single morally inspired man can make all the difference. Wilson, as we know, went to Versailles with the hope of making the postwar world very close to perfect. His Fourteen Points embody an ideal vision. The world that emerged from Versailles was far worse than Wilson dreamed. Nevertheless, it is painful when a historian holds the American president chiefly responsible. Wilson predictably wielded less influence than the two Western powers that had borne the brunt of the fighting since 1914; the blood of Britain and France had purchased a good deal more gravitas than the United States could bring to the table. Between the unyielding revanchism of Georges Clemenceau and the territorial greed of Lloyd George, the just, nonpunitive settlement that Wilson desired was doomed from the outset. It is far fairer to Wilson to note that he did what he could and that the treaty would have been more calamitous still if not for his idealistic influence.

Meyer’s book seems cursed with ill timing. Written before the advent of the current administration, its portrait of Wilson as an insecure political neophyte, hostile to free speech and incapable of accepting criticism, would undoubtedly have felt more persuasive if his readership had not just experienced a few months of the Real McCoy. A flawed man, Wilson was nonetheless superbly educated and impeccably motivated. Though his definitions of justice have not aged gracefully, he earnestly strove for the betterment of the world. To those who concentrate on his failures, a daily message now emerges from Washington: “You ain’t seen nothin’ yet.”

To those who concentrate on his [Wilson's] failures, a daily message now emerges from Washington: “You ain’t seen nothin’ yet.”

Meyer’s work is more troubling still in its sympathy with Kaiser Wilhelm’s Germany, which, in his account, was dragged unwillingly into the war. He is also quick to palliate Germany’s crimes against neutral Belgium, arguing that they emerged “not [from] a desire for conquest but pure raw fear.” In the war’s first days, German armies put scores of Belgian towns to the torch and massacred thousands of civilians. The pure, raw fear of a child who sees her father shot and her home destroyed seems to weigh little in Meyer’s moral calculus. Mr. Meyer also elides a sinister truth: Germany’s treatment of civilians early in the war set the moral tone for much that came after. It fostered a mindset that made no distinction between combatants and civilians and, across Europe for years to come, helped to make sheer murder respectable.

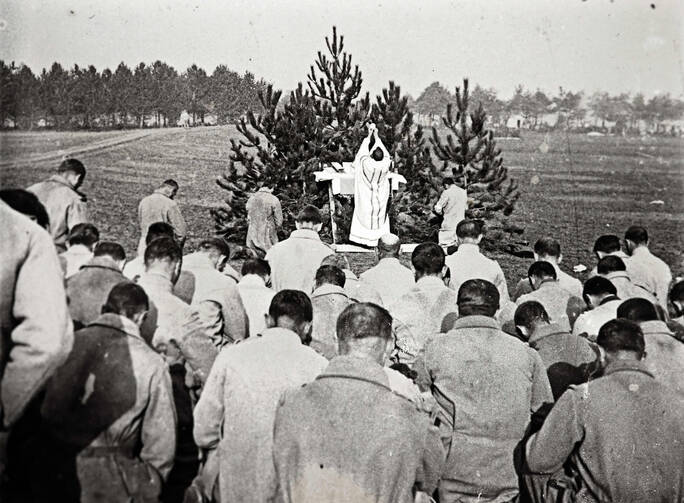

This mindset and its consequences are explored in impressive, though pessimistic fashion by Robert Gerwarth’s The Vanquished: Why the First World War Failed to End. The volume would be remarkable for its bibliography alone: its superb compendium of sources written in more than a half dozen languages is a trove for would-be enthusiasts and scholars. Gerwarth tells a story too seldom told: the breakdown of governmental authority and the ensuing chaos that afflicted the nations defeated in World War I. Spanning from Germany and Hungary to Bulgaria and Turkey and beyond, the narrative isn’t pretty. The Vanquished is strewn with the darkest of images, from clergymen left to die after their eyes had been gouged out and their hands roughly amputated to women forced to dance naked as their husbands watched before being gang raped and cut to pieces.

The grim nature of the subject matter, coupled with occasional densities in Gerwarth’s prose style, makes The Vanquished a less than easy read. However, it is a book that rewards patience and one whose virtues become more apparent when one has arrived at the final page, and perhaps still more a few days later. Gerwarth is scrupulous in his factual narration of a series of national tragedies, relating how, one by one, the defeated nations of Europe succumbed to their most dreadful instincts. These stories, though roughly parallel in their trajectories, emerge from a variety of causes: the lack of political will in Italy to defend its parliamentary regime against the rise of Mussolini; the blockade-induced famine in Germany and the marauding soldiers of the country’s Freikorps, who were too habituated to warfare to revert to peaceful existence once the armistice was signed; the anti-Bolshevist backlash in Hungary; unreasoning ethnic loathings in Poland, Turkey and elsewhere.

The great value of Gerwarth’s study lies equally in its masterful exploration of the psychology of defeat and in its applicability to our own fraught political moment. In his terse and moving epilogue, Gerwarth warns against the conditions that give rise to the logic of violence. He decries the tendency, so rife after the Great War and so ominously recrudescent today, to dehumanize and criminalize the ethnic and religious Other; the refusal to distinguish the dangerous enemy from the abject and innocent refugee; the arrogance and greed of victorious nations that fostered unbearable humiliation among the defeated and stirred the passions of terrible revenge. Gerwarth tales of suffering and barbarism can and should be read as the most potent of parables.

Meyer and Gerwarth agree that the Great War and its aftermath sounded the death knell for the belief that the Western world was on an unshakable path of progress, destined to rise to ever greater heights of decency and enlightenment. A hundred years after that war, we are all persuaded that progress is no inevitability. Yet the lessons of these volumes also include the necessity of hope; even a dubious optimism and a forlorn faith in one another are preferable to surrendering to distrust and despair.

This article also appeared in print, under the headline “Amid the wreckage of World War I, avoiding the impulse to despair,” in the Spring Literary Review 2017, issue.