The director Raoul Peck learned at a very young age the importance of understanding cultures different from his own. Born in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, in 1953, he left when he was 8 years old for the Democratic Republic of the Congo, where his father worked for the United Nations. Mr. Peck describes the cultural shock he experienced when he arrived in Kinshasa and “discovered a totally new world,” one unlike the Africa he had seen portrayed in Hollywood movies. It was this experience that would lead him to understand the importance of deconstructing the world he knew, which would deepen in his teenage years as he discovered the writing of James Baldwin and became involved in politics.

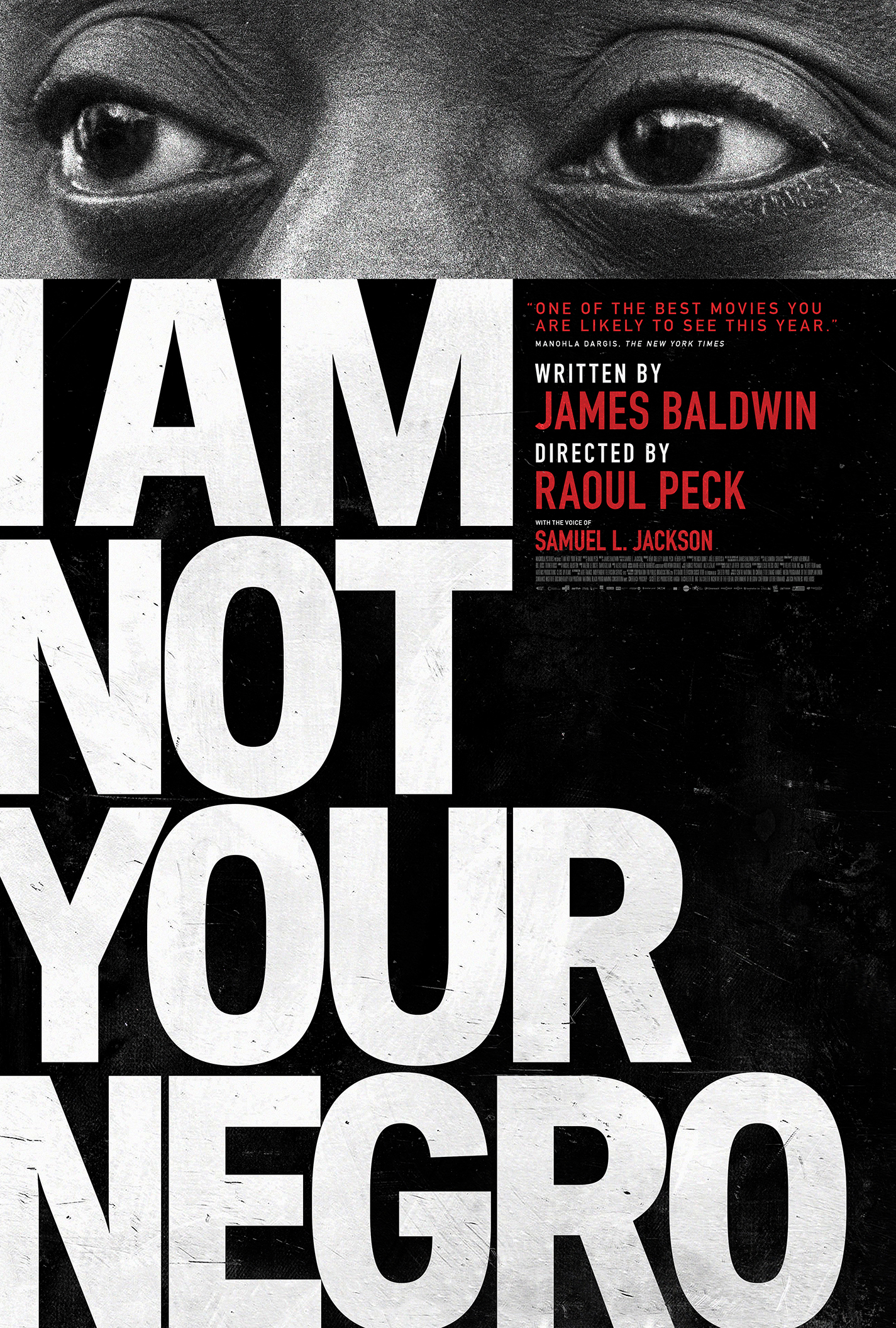

This dismantling has played a significant role in his work, evident in films like “Lumumba” and “Sometimes in April,” which depict the life of Congolese leader Patrice Lumumba and the Rwandan genocide, respectively. “I Am Not Your Negro,” out in theaters this Friday, is no exception. Mr. Peck centers this story around James Baldwin’s Remember This House, the author’s unfinished manuscript on his relationship with Medgar Evers, Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr. Nominated for best documentary at this year’s Oscars, the film creates a parallel between the civil rights movement of the 1960s and the Black Lives Matter movement. This week, the director screened the film for students at Harlem Renaissance High School in New York. (The school, which Baldwin attended, was formerly known as P.S. 24.) Peck also provided a curriculum to help students discuss the author and his works, emphasizing his belief that reading Baldwin “should be an obligatory part of one’s education.”

I met with Mr. Peck at Magnolia Pictures to discuss his work, Baldwin and “I Am Not Your Negro.” This interview has been edited for clarity.

Olga Segura: I think as Americans, we often forget that immigration exists outside of the 50 states. What was that experience like for you?

Raoul Peck: Well, first of all it was a cultural shock…. When I was in Haiti, I left, I was 8, but my knowledge of Africa was basically through Hollywood films depicting the jungle, safari-type of stories. When I arrived in the Congo, I really thought that I would be welcomed by a bunch of savages and dancing around the airplane… And that was kind of a shock for me, a great shock, because I was discovering a lot of riches, something that I did not know existed. But I also became suspect of stories, of movies, of Hollywood because I felt that in fact it was a lie. I think all my life, that’s what made me close to Baldwin, that I always had to deconstruct whatever I was fed with.

And then when you have the chance to be somewhere else than your own country, I think you look back to your own country differently. You look back at other places differently. It’s like you’re adding another layer to your analysis. It’s like you add an additional perspective…. [Baldwin] had to leave his country very early on, when he was in his early 20s. And that made the difference. He had a better view and a better analysis of the United States by being elsewhere, by looking back to his world from Paris or from Turkey.

Segura: You talked a little bit about arriving in Africa and how you started to feel suspicious about Hollywood films. And then you studied film in West Berlin. So was this need to offer a different perspective that you weren’t finding in movies or shows that you were watching part of what inspired you to get into film?

Peck: Um, not really. My story with film is kind of different because I started with photography because my father was a photo buff. He had all sort of cameras, and I grew up with that. I have so many photos when I was 2 or 3. I remember touching those cameras and so it was something that was always in the house, wherever we were.

So film for me was something you do as a hobby. It was never a profession. Coming from a poor country like Haiti where you had to make a living, being an artist was a luxury or it was something you did because you messed up your life…. [The desire to create films] came much later. And I, by the way, studied something totally different. I studied economics. I studied industrial engineering. It wasn’t until later, when I was around 26, that I really decided to go to film school. But before I always thought, I would do film. I would make films on the side, work in my profession, make a living and provide for a family. But quite frankly, I discovered very early on that it was not possible.

Also, because I was involved in politics, my time in Berlin was an extraordinary time. I went there when I was 17, 18. Berlin at the time...had refugees from many countries… So all these people, you know, we were working together… It was really a time of international solidarity. You learn a lot through that, and politics becomes an integral part of who you are and what you do. You felt responsible for the whole world. And it was never about yourself.

I read Baldwin around this time, and he never left me. I use his writing in many occasions, both professionally and personally. He helped me understand the world. He helped me find my own place in the world.

I read Baldwin around this time, and he never left me.

Segura: So talk to me about the process behind “I Am Not Your Negro.” How long was it, from inception until completing the film?

Peck: The idea of tackling Baldwin in film came around 10 years ago, when I felt that there were extensive tensions, not only in this country here but throughout the world. There was clearly a lack of sensitivity about minorities, about women, about a lot of issues that were important to me, and that we were slowly pushing aside. I felt it was like we were losing a lot of the things that we had won over the years, including the death of the civil rights movement… So I felt that we really needed Baldwin.

At the same time, I was seeing how little he meant to a new generation and how even some people were pushing him aside as either a has-been or as a minor author, which is scandalous. So I thought, it was time to bring him back and make sure that this legacy will stay. We live in a time of pictures, of images, of film. I knew that if I succeeded in making something like the essential Baldwin, that he would never go away.

The Baldwin estate has a reputation for not even answering inquiries. But I took my chance and I wrote a letter to the estate and I got the response within three days, which was exceptional.

And they invited me to come to visit them. I went to Washington and I met Gloria Karefa-Smart, James Baldwin’s younger sister, who was his assistant for many years, almost all of her life. And I just realized that she knew my films. She loved in particular “Lumumba.” And she opened everything to me. They were very patient with me. During the first four years I really tried different things. I raised money to write a screenplay. I worked with a playwright. I tried a mixed genre, between documentary and narrative. I went from pure biography to just using one of the novels. But all this was not satisfying because I knew I needed to make a film that would be exceptional and even unique in the sense that there is no way the industry would let you make one, two, three, four films on Baldwin.

One day Gloria gave me 30 pages of notes with the title Remember This House, and this letter to his literary agent. She just told me, “Here, Raoul, you will know what to do with this.” The idea of connecting Medgar Evers, Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, writing the story around those three men, who know of each of other and were even very far away from each other and came closer together and then were all three assassinated, telling the story of America through these lives and these deaths was incredible for me. And this took time. I didn’t want to have any other voice, didn’t want to have that kind of conversation, that kind of paternalistic opinion on Baldwin or expert on Baldwin. I wanted to have Baldwin.

Segura: One of the most jarring things for me about your film was hearing Baldwin’s words juxtaposed over news footage of events like the Ferguson unrest following the death of Michael Brown. And you use this to tie the civil rights movement of the 1960s to the Black Lives Matter movement of today. Even as someone who’s very familiar with all of these things, who’s very involved, it was still very shocking for me, particularly because it’s been almost 30 years since Baldwin died and everything he says seems as relevant as ever. Is that what you want audiences to take from this?

Peck: That’s the fundamental question. We see why Baldwin is efficient, because he went to those fundamental issues. And what has really changed, fundamentally, in this country? Is there less inequality? Is the problem of poverty solved? Is the problem of racism solved? No. Thirty years is nothing in the life of a country and we can’t just pretend as if everything is beautiful. That’s why this voice is essential and I can understand that the shock is real. While working on this, although I knew all those things, I was seeing how the daily news was making this story even sharper.

And yes, that was the point of it all, to make his words present. I had to link it to the layers of images, like those black and white images of the civil rights movement, the fire hose, etc. I colored them to bring them closer to today. And I used Ferguson as black-and-white footage, so that it’s a full circle. My job was to… not only put all those different layers, but put them in context and connection.

So that’s what allows you to go back and forth as a viewer, to think about it, to ask yourself: What does it mean?

Kendrick Lamar, for me, is one of the most interesting poets.

Segura: I know people have talked a lot about your choice of Samuel L. Jackson as narrator. But another thing that I particularly loved was that you ended with Kendrick Lamar’s “The Blacker the Berry.” How did you arrive at that music choice?

Peck: As I was saying, this movie has many layers and that’s what makes its quality…. And all those subtleties, that’s what makes the films rich, but also, it’s like a symphony. You use certain levels of music and rhythm in symphony. The images are one part and also the music is one. You flush out jazz, blues, spirituals, musicals, Ray Charles, Lena Horne. All this is also mapping a story, a political story.

So by the time I got to Kendrick Lamar, it’s also closing a circle and making truth of today. Kendrick Lamar, for me, is one of the most interesting poets. His political analysis uses rap and music to carry his message and his art. And I felt it was necessary to go all the way to this connection with the generation of today.

Because it’s about them. How do they learn through the work of their elders? This young generation, they are confronted with this complex world. So I felt it was important to come back to Lamar and open another window for them to get into the film, to get into these questions it’s asking.